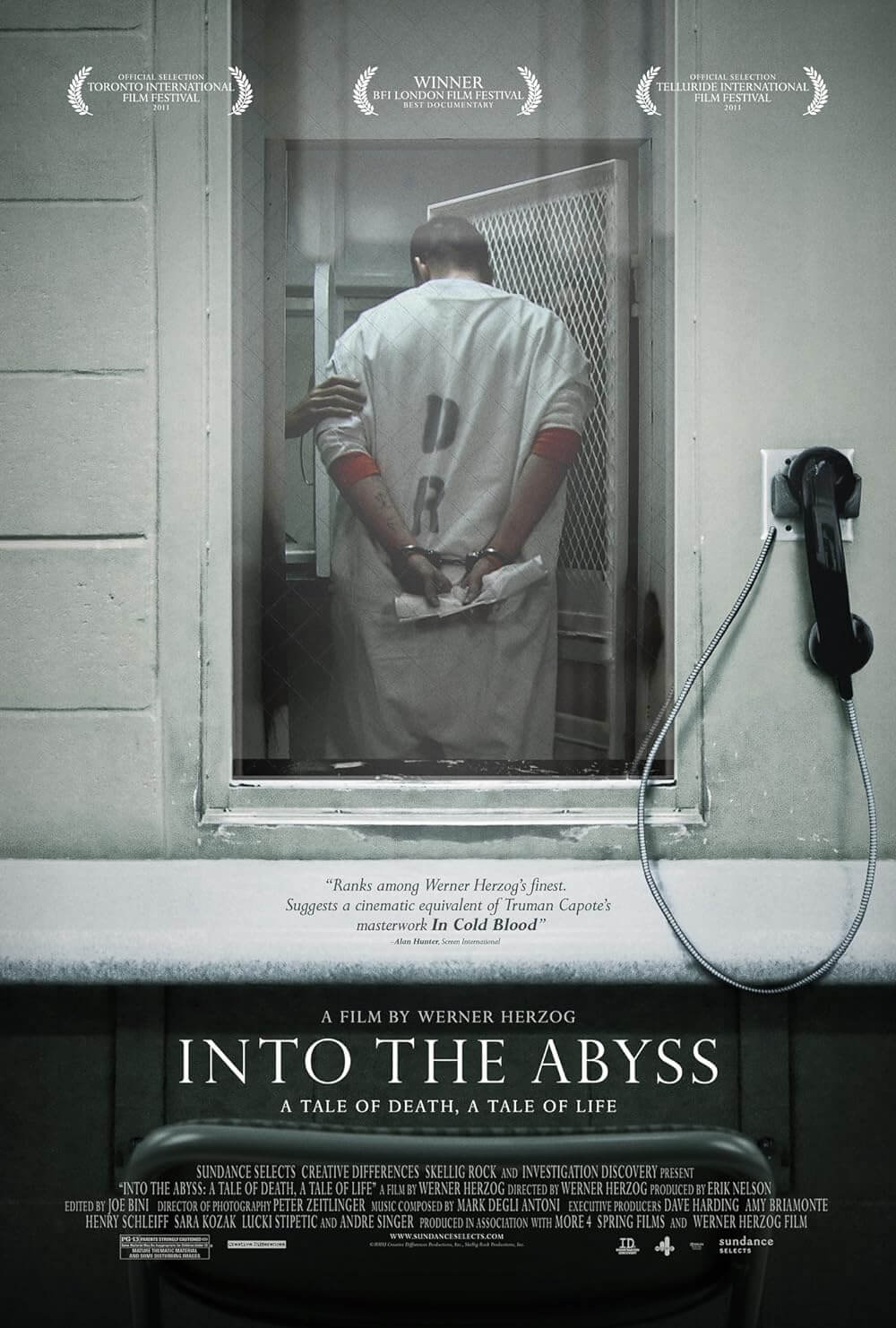

Into the Abyss

By Brian Eggert |

In 2002, Jason Burkett and Michael Perry, teenagers from Conroe, Texas, wanted a car. They eyed a red Camaro belonging to a nurse named Sandra Stotler, who was in the middle of baking cookies when her assailants knocked on her door. After their “master plan” had run its course, three people died at their hands, including Sandra, her son, and his friend. Since neither party was very bright, Perry and Burkett showed off their new acquisition and gave joyrides, claiming they had won $4,000 from a lottery ticket and bought the car themselves. After they were captured and prosecuted for their crimes, Perry was sentenced to death and the execution was carried out on July 1, 2010, while the jury gave Burkett a life sentence, in all likelihood because of Burkett’s father, a regretful prison inmate himself, begged the jury for mercy. Though both were convicted, it seems Perry received death because no one was there to beg for his life in a tearful scene. Is that fair?

Werner Herzog’s documentary Into the Abyss maintains an unexpected degree of profundity, in that the filmmaker voyages to the “capital punishment capital of the U.S.A.” to launch an attack against capital punishment, but he finds something else entirely. What he discovers is something much less political and far more human. Herzog, who never appears onscreen, interviews those involved in the murders, Burkett and Perry, their families, as well as the families of the victims. In his quietly intense German accent, he asks questions fuelled by curiosity in the search for truth, rather than a search for facts. He doesn’t shrink away from asking difficult questions, and sometimes his curiosity yields unexpected results. When he solicits death row chaplain Richard Lopez to “describe an encounter with a squirrel,” the response becomes one of those great Herzogian discoveries and the film’s most spiritual scene.

The doc incorporates police photos and actual crime scene footage shot on VHS in 2002 into original footage shot by Herzog’s cameraman Peter Zeitlinger. But for the most part, the film is comprised of stationary interviews, Herzog off camera, his subject locked in an unmoving frame. When he conducted the interviews, he was meeting these people for the first and only time; he was talking to Perry just days before the man’s execution. The frankness and emotion he’s able to eke out using his unassuming interview approach is staggering, as most of his interviewees bear an incredible sadness they no doubt want to bury, yet they seem so willing to tell all. Perhaps this is because, aside from one or two leading questions, Herzog is a master listener. In a way, his camera listens too. Long after his interviewee has finished with what they have to say, Herzog remains silent and the camera holds on its subject. An awkward moment occurs: The subject’s “interview face” slowly disappears, and we see what they’re really feeling, how uncomfortable or in pain they are. This is a trademark of Herzog’s documentaries, and part of what makes them so penetrative.

Herzog’s method as an artist and documentarian, and his odd brand of warmth, are about as far as one can get from his hard-living Texan subjects. Whether citizens from Conroe or the neighboring town of Cut and Shoot, everyone he talks to has a sordid past or family members with a criminal record, to an almost unbelievable extent. One account details how a man was stabbed with a massive screwdriver under the pectoral, but because he was due at work in a half-hour, he opted against a hospital visit. We meet Sandra’s daughter Lisa Stotler-Balloun, a woman who has lost almost everyone in her family due to the killings and a shocking series of accidents and disease and suicide, and yet somehow she retains some sense of composure. Now she unplugs her phone because she can’t stand to receive any more bad news. The people raised in these communities seem to have no chance; either their families are too poor to survive without some kind of criminal supplementation, or drugs and alcohol spoil them. Burkett’s father, Delbert, had a football scholarship to the University of Texas before he dropped out to support his habit. You can’t make this stuff up.

The film’s merits as true crime nonfiction have been compared to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, but the result is far more openly soulful and searching thanks to Herzog’s human compassion. When speaking to Perry, he tells the 28-year-old, who still looks like a boy, “I don’t have to like you,” but he understands their situation and treats them with dignity regardless. As much as these men make claims to their innocence or declare the other is the sole man responsible, despite their being no doubt about their guilt, Herzog never censures them or probes them for their version of the story. He’s less interested in factual details about their killings than the emotional state of someone behind bars for the rest of their life, or someone who has only a few days left before his state puts him to death. By humanizing the criminals and victims, Herzog makes his strongest case against capital punishment, indirect though it may be.

Herzog’s most significant argument against capital punishment resides in Fred Allen, a former captain employed on Huntsville’s Death Row. Over the years, Allen had completed upwards of 125 executions, each carried out with professionalism. This was until he carried out his first execution of a woman (in the last 30 years, Texas has executed more than 450 men, but only 6 women). The incident shook Allen to the bone; after, he couldn’t continue and even gave up his pension when he left the job. On the flip side, Herzog interviews Jason’s wife, Melyssa, who met Jason via correspondence as she oversaw Jason’s appeals with her father from Nebraska. When she discovered they had fallen in love, they were married on paper. When Herzog conducted the interview, she was pregnant; however, Texas does not allow conjugal visits. Figure that one out for yourselves. Herzog seems to say that there’s still a worthwhile existence for an imprisoned-for-life inmate to have, even while he asks Melyssa about the phenomenon of “death row groupies.” Is this the kind of life that’s being robbed by Perry with his execution?

Herzog’s initial remarks about the death penalty become Into the Abyss’ roundabout focal point for a larger discussion about finding humanity in the worst of places, be it behind bars or simply in Texas. As much as this film is about the death penalty, it is about the people whose lives were shaped by a senseless crime. Whatever expectations you have entering this documentary, no matter how adamant your feelings are for or against capital punishment, they become another feeling entirely by the time it’s over. And if your views haven’t changed, at the very least, Herzog has given you much to consider—not in terms of an intellectual argument against the practice, but an intuitive argument that exposes the complexities behind any human life, and thus the “Old Testament” logic of reducing a penalty sentencing down to a single black-or-white (life-or-death) decision. As always, Herzog uses his ability to ask the right questions, let his subjects talk, and leave his camera to dwell on their sad faces. Easily the most affecting documentary by Herzog, who also released the transportive Cave of Forgotten Dreams earlier this year, Into the Abyss is also one of his most challenging.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review