Interstellar

By Brian Eggert |

Humanity has grown beyond its means. Centuries ago, the number of human beings on the planet reached into the millions. Now our numbers are approaching 7 billion and that number is expected to double, and then some, by the end of this century. How can Earth’s natural resources possibly keep up? Along with rampant reproduction, humans have explored the planet’s surface to its limits. After conquering the Western frontier, few places on Earth remain unexplored. And with the decline of manned missions into space, our ever-growing species has become stagnant, growing outward, on top of ourselves, and apathetic; whereas humanity is often at its best and most ambitious when it’s exploring. Human beings are curious creatures, and when we stop exploring, we stop developing as a species. And yet, a final frontier—which, in itself, is endless—awaits out in the stars. This could not only provide a solution to overpopulation and dwindling natural resources, but also to humanity’s desperate need to continue growing, both in terms of pure numbers and also in sociological progress. Deep space missions may seem like science-fiction at present, but so was landing on the Moon in 1961 when JFK announced a space race.

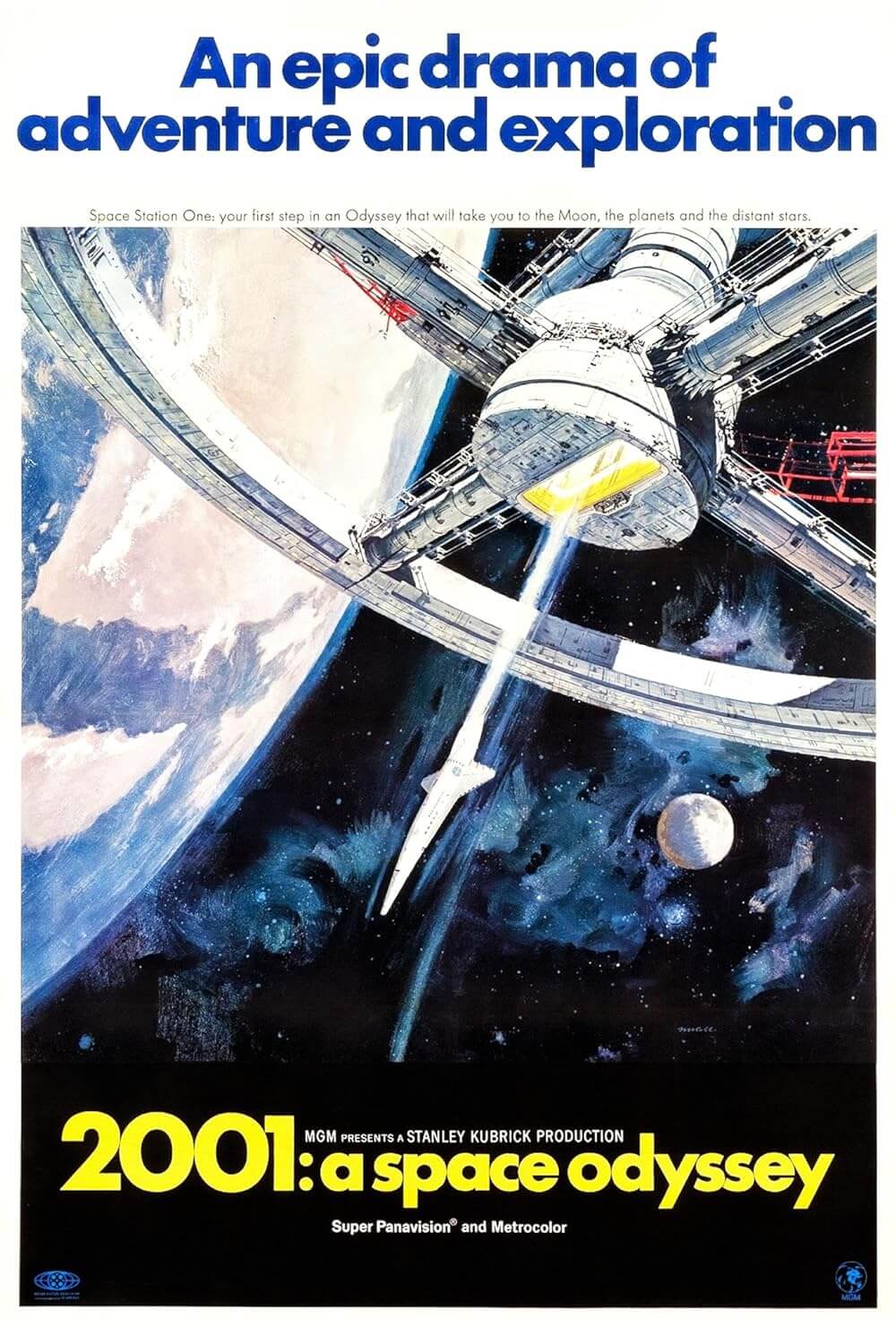

Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar brings us one very necessary, yearning step closer to a realistic vision of a manned space flight into deep space, just as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey did for a Moon landing and beyond in 1968. Long in development with Steven Spielberg at the helm, the film is the dreamchild of producer Lynda Obst and her scientific collaborator on Contact (1997), theoretical physicist Kip Thorne. Johnathan Nolan wrote the script’s first draft for Spielberg and, after studio shuffling caused Spielberg to drop out, the writer’s brother took over the $165 million co-production—an unheard of partnership between Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures. Director Nolan retooled his brother’s screenplay to meet his own needs for emotional urgency and approached the production like an event, his unique brand of secrecy jealously guarding its many secrets. Even its distribution is epic; his cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema shot in anamorphic 35mm and IMAX photography, and a special 35mm roadshow print screened at select theaters. But more significant is how Nolan’s film calls to humanity and asks, What comes next for the human race, apathy or action?

Today, underfinanced institutions such as NASA or SpaceX have almost no drive or need to send an astronaut to Mars, much less explore beyond our galaxy. The first brilliant aspect about the Nolans’ screenplay is how it creates a believable futureworld where humanity has exhausted its earthly means and has no choice but to look for another planet to survive. Tapping into history, the film remembers the single worst man-made natural disaster, the Dust Bowl (complete with interview segments from Ken Burns’ excellent documentary on the subject), and conceives a similar disaster. With crops dwindling from an omnipresent blight, lacking food resources have thinned out the human population. Wheat and okra have gone extinct; corn may be next. Governments have transformed into agrarian societies with little infrastructure. Towering storms of dust blow through rural America, where former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) operates a corn farm with his two children Murph and Tom (Mackenzie Foy, Timothée Chalamet), and the father (John Lithgow) of his late wife. Inside their dust-ridden house, Murph believes her mother’s ghost has been sending her signals via Morse code and knocking books off her shelf. Sure enough, the communications do contain a code, but it’s not a ghost.

Today, underfinanced institutions such as NASA or SpaceX have almost no drive or need to send an astronaut to Mars, much less explore beyond our galaxy. The first brilliant aspect about the Nolans’ screenplay is how it creates a believable futureworld where humanity has exhausted its earthly means and has no choice but to look for another planet to survive. Tapping into history, the film remembers the single worst man-made natural disaster, the Dust Bowl (complete with interview segments from Ken Burns’ excellent documentary on the subject), and conceives a similar disaster. With crops dwindling from an omnipresent blight, lacking food resources have thinned out the human population. Wheat and okra have gone extinct; corn may be next. Governments have transformed into agrarian societies with little infrastructure. Towering storms of dust blow through rural America, where former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) operates a corn farm with his two children Murph and Tom (Mackenzie Foy, Timothée Chalamet), and the father (John Lithgow) of his late wife. Inside their dust-ridden house, Murph believes her mother’s ghost has been sending her signals via Morse code and knocking books off her shelf. Sure enough, the communications do contain a code, but it’s not a ghost.

When Cooper and Murph follow where the code leads, they find a secret NASA installation where Professor Brand (Michael Caine) makes plans to find another planet for earthlings to colonize. A wormhole discovered near Saturn, seemingly put there by design by an alien race, offers a gateway to another system where three habitable planets could provide a potential new home for humans. Other one-man astronaut probes have already gone through to explore potential homeworlds. Now Brand wants Cooper to pilot a larger mission to confirm their findings, which means he must leave his family behind. The parting is worse for Murph, who refuses to speak to her father since he doesn’t know if or when he’ll return. But Cooper is an explorer at heart and knows humanity is never better than when it’s out there discovering: “We’ve forgotten who we are,” he says at one point. “Explorers, pioneers. Not caretakers.” His crew of astronauts on the Endurance mission—Doyle (Wes Bentley), Romilly (David Gyasi), Brand’s daughter Amelia (Anne Hathaway), and blocky interactive robot TARS (Bill Irwin)—believe in their years-long mission through shifting space-time and know the possibility that, by the time they return, everyone they know on Earth may be dead. Worse, they may get back too late to save anyone.

What follows is not only an exploration of three planets—each near a black hole named Gargantua—that may contain elements to sustain the future of the human race, but also a deeply emotional, philosophical, and scientific consideration of several lasting science-fiction themes. It’s all presented in a near-three-hour epic that, like Nolan’s entire Dark Knight trilogy or Inception, delivers a fully developed concept that uses every component in its complex narrative structure, and finally wraps around in a Mobius strip. At the forefront of Cooper’s story is his pain over leaving his children; through transmissions received over the mission’s years, he watches Murph and Tom grow older (now played by Jessica Chastain and Casey Affleck). From this, the film weighs our individual needs against the needs of the many. Should the mission be Prof. Brand’s Plan A, to somehow transport the Earth’s population to a new planet, or his Plan B, to establish a new colony and forget about finding passage for Earth’s doomed inhabitants? But Insterstellar also plunges into the fascinating plot device of relativity, where shifts in gravity slow the passage of time, not unlike the various levels of dream-reality in Inception.

In a film where relativity plays in the same sandbox as quantum and theoretical physics, the Nolans suggest that another force of Nature impels the crew. Love itself has a similar pull as gravity when all known laws of space-time break down and the universe becomes a five-dimensional abstract. In that sense, love may pull a character this way or that when the laws of physics are being rewritten. This turn from ultra-scientific (to the degree of being over the heads of some viewers not versed in space-time theory) to arguable sentimentalism may divide reactions between science buffs and romantics. But Interstellar’s detractors are the same group that accused the brilliant Contact (which also starred McConaughey) of not meeting expectations for its pointed lack of aliens. As much as the film considers a fantastical journey to space to rival the realism-meets-mindbender quality of 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s more about its protagonist’s journey there and back again, as well as our culture seeing ourselves not as individuals but as a species that should endeavor to improve itself.

In a film where relativity plays in the same sandbox as quantum and theoretical physics, the Nolans suggest that another force of Nature impels the crew. Love itself has a similar pull as gravity when all known laws of space-time break down and the universe becomes a five-dimensional abstract. In that sense, love may pull a character this way or that when the laws of physics are being rewritten. This turn from ultra-scientific (to the degree of being over the heads of some viewers not versed in space-time theory) to arguable sentimentalism may divide reactions between science buffs and romantics. But Interstellar’s detractors are the same group that accused the brilliant Contact (which also starred McConaughey) of not meeting expectations for its pointed lack of aliens. As much as the film considers a fantastical journey to space to rival the realism-meets-mindbender quality of 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s more about its protagonist’s journey there and back again, as well as our culture seeing ourselves not as individuals but as a species that should endeavor to improve itself.

Nolan’s visionary approach reaches every aspect of his production, supporting the narrative’s severity and importance. The spatial effects inspire awe, recalling Douglas Trumbull’s work on The Tree of Life (2011). Hans Zimmer’s organ score imbues the film with a cathedral-grade gravitas, reverberating through the picture like Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Other details, such as how Nolan avoids using sound in space exterior scenes (where sound cannot occur anyway), implant sometimes beautiful and sometimes haunting visuals into our heads. However, Nolan’s most valuable component is McConaughey. The actor’s soulful turn searches for meaning and weighs the film’s arguments between devoted familial bonds and the advancement of the species. His breakdowns instill infectious tears and perpetuate the film’s emotional core. Hathaway, Chastain, Affleck, and Caine are all excellent. Though, particular attention should be paid to Matt Damon, who appears later on as this film’s narrative equivalent of HAL-9000, charming and so focused on the mission that he terrifies.

Rarely do epics of this scope and intelligence reach theaters anymore; such serious commercial filmmaking seems like a market almost exclusively maintained by Christopher Nolan. His primary inspiration is Kubrick, more specifically 2001: A Space Odyssey, both of which have an undoubted influence on the Nolans, their story structure, and their intended impact on the future of space exploration. For this, Interstellar is not just an engrossing, blockbuster-sized, artfully made, thinking-person’s picture; it’s also a landmark that calls for humanity to stop seeing themselves as earthlings and begin to envision themselves as citizens of the universe. (Cooper’s lines “Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here,” resonates.) This outlook, along with the film’s university-level descriptions of intergalactic wonders, may divorce some lesser-versed viewers from the material. But Nolan has never been about catering to the lowest common denominator; quite the opposite. And so, his picture is a resounding challenge that poses questions human beings either don’t ask enough or have stopped asking altogether. Interstellar shows us that the answers reside in the stars.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review