Insomnia

By Brian Eggert |

At first glance, Insomnia seems like an undemanding choice with which director Christopher Nolan should follow his feature-length debut, 2001’s Memento, a landmark motion picture composed of intelligent narrative and structural trickery. By contrast, what could be more straightforward than a Hollywood remake of a foreign—not to mention linear—cop thriller? And yet, as with all his films, Nolan treats his narrative with grand symbolism to reflect the layers of the story. Looking back, the picture’s themes of obsession, means justifying ends, and self-deception fit nicely into the director’s body of work, but here he explores them in such emotionally engrossing and suspenseful ways that it catches the audience off-guard, if only because on the surface the material looks so typical. Just when we think we’ve seen every psychological thriller about a cop chasing a killer, here’s a film that has more in common with a film noir tale. How ironic then that the entire picture takes place under the never-setting sunlight of the northern hemisphere.

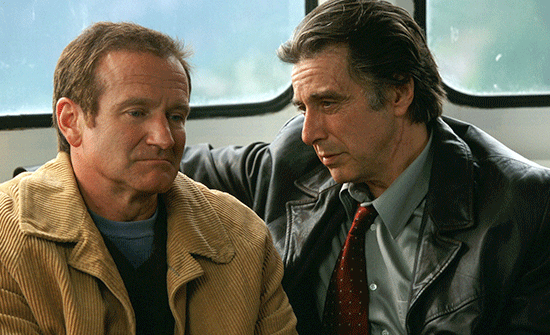

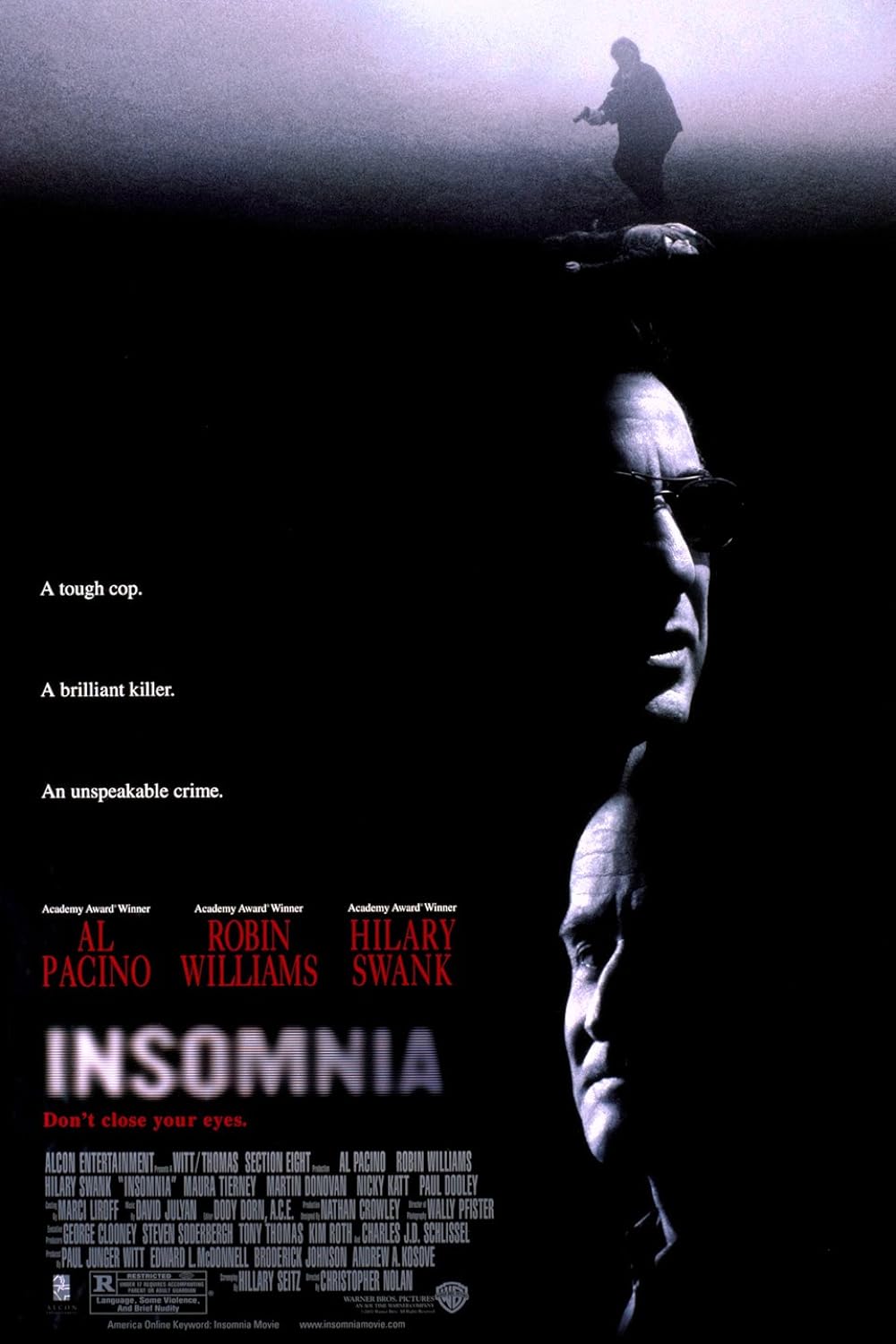

Based on Erik Skjoldbjaerg’s Norwegian original from 1997, the story follows a seasoned Los Angeles homicide detective who flies to the sleepy town of Nightmute, Alaska, to help the inexperienced locals investigate the brutal murder of a high school girl. The detective, played by that venerable movie cop Al Pacino, finds himself inescapably blackmailed by the killer, creepily realized by Robin Williams. On that hook, the film was released during the summer movie season of 2002 and made substantial profits worldwide for its producers at Section Eight, Steven Soderbergh and George Clooney’s former production company. The reviews overall were positive, many arguing that Nolan’s film surpassed the original. And indeed it does. But time and Nolan’s popular subsequent efforts—his Dark Knight Trilogy, The Prestige, and Inception—have slowly eclipsed Insomnia, leaving it unduly forgotten since its release. After all, there are no superheroes, no magic tricks, and no dreams-within-a-dream, just a morality tale disguised as a detective thriller.

Det. Will Dormer (Pacino) agrees to his Alaskan manhunt to escape the burning magnifying glass of Internal Affairs back home. They have good reason to believe Dormer is guilty of planting evidence to secure convictions, and his partner Hap Eckhart (Martin Donovan) wants to cut a deal to save himself jail time. But if Dormer’s offenses in the name of crimefighting, committed with the best intentions, are exposed, then I.A. will begin looking into his past cases, and potentially a whole slew of convicted killers and rapists will go free. When Dormer and Eckhart arrive in Nightmute, they’re enthusiastically greeted by local officer Ellie Burr (Hilary Swank, a pinnacle of innocence and virtue), who studied Dormer’s cases at the academy and worships the man’s legacy. Along with a smarmy local lead detective (Nicky Katt), Burr hands over the case of the murdered 17-year-old Kate to Dormer, who quickly sizes up their killer’s profile. The perpetrator isn’t the victim’s angry, abusive high school boyfriend as everyone seems to think; it’s her mystery out-of-town “friend” who no one seems to know—a meticulous first-time killer who washed Kate’s hair and clipped her fingernails before dumping her body.

Using a few simple clues, Dormer sets a trap for the killer at a lake house engulfed in fog. His ambush works, save for the bungling local cop who accidentally gives away their position. A chase ensues into the mist, with cops spread out and the killer on the loose. In the blind chaos, Dormer sees a shape at which he fires, only to discover he’s tagged his partner, a man with a wife and kids. A panicked but shrewd series of decisions allow him to spin the incident in his favor, suggesting Nightmute’s nameless killer shot Eckhart and escaped in the fog. The deception conveniently frees Dormer of any worry of Eckhart cutting a deal with I.A., but it saddles him with unshakable guilt. Did he know it was Eckhart and fire anyway? He doesn’t know anymore. The film’s setting plays a crucial symbolic role: Nightmute’s midnight sun never stops blaring and won’t allow Dormer to sleep; he blocks the windows of his hotel room, but light still gets through, and he spends countless hours chewing gum and staring at his alarm clock, images of Eckhart flashing into his mind.

Using a few simple clues, Dormer sets a trap for the killer at a lake house engulfed in fog. His ambush works, save for the bungling local cop who accidentally gives away their position. A chase ensues into the mist, with cops spread out and the killer on the loose. In the blind chaos, Dormer sees a shape at which he fires, only to discover he’s tagged his partner, a man with a wife and kids. A panicked but shrewd series of decisions allow him to spin the incident in his favor, suggesting Nightmute’s nameless killer shot Eckhart and escaped in the fog. The deception conveniently frees Dormer of any worry of Eckhart cutting a deal with I.A., but it saddles him with unshakable guilt. Did he know it was Eckhart and fire anyway? He doesn’t know anymore. The film’s setting plays a crucial symbolic role: Nightmute’s midnight sun never stops blaring and won’t allow Dormer to sleep; he blocks the windows of his hotel room, but light still gets through, and he spends countless hours chewing gum and staring at his alarm clock, images of Eckhart flashing into his mind.

Then, as if to plague him further, Dormer receives calls from the culprit himself, who tells him that he saw the detective shoot Eckhart on the foggy beach. It’s an oddly calm, even soothing voice, an understanding one that admits he suffered the same kind of insomnia Dormer’s suffering now. “We’re partners in this,” the killer’s voice (Williams) explains, claiming he didn’t mean to kill Kate just like Dormer didn’t mean to kill Eckhart, and that if Dormer agrees to help him pin the murder on Kate’s roughhousing boyfriend, he won’t tell anyone about Dormer’s shooting. A trifecta cat-and-mouse game begins. Dormer plays like he’s willing to work with the killer, a local crime novelist named Walter Finch, while underhandedly working the evidence, so it points to Finch. But Finch protects himself and preys on the dim-witted local cops who follow whatever breadcrumbs he leaves for them. Meanwhile, Burr has been assigned to write up a report on Eckhart’s death; in doing so, she takes advice from Dormer, who encourages this overachiever to leave no pebble unturned, perhaps out of his own unconscious desire to be captured so he can finally rest, get some sleep, and be free of his guilt.

Haggard, bags under his eyes, cracked pale skin, his gray hair peppering his black mane, Pacino has never before looked this vulnerable or worn down in one of his many cop roles. In titles prior to Insomnia, ranging from Sea of Love (1989) to Heat (1995), Pacino is always the untouchable hotshot who gets the bad guy, even if he sometimes regrets it. And after Nolan’s film, Pacino’s star cop performances continued, the actor’s increasingly orange-tanned leather skin and dyed jet-black hair becoming almost self-parodying in junk like 88 Minutes and Righteous Kill (both from 2008). The depth of his textured performance here enhances the film’s themes of guilt and obsession, both of which, along with the midnight sun, keep him from sleeping at night. Pacino staggers around confused as the story progresses, and Dormer goes several days without sleep, his eyes wandering like a blind person’s, never quite zeroing in on a subject. Except when Dormer faces Finch—only then does Pacino’s character briefly snap out of his unsleeping cloud to engage the killer in exchanges shot in long, involving takes. It’s one of his best later-career performances, a period otherwise riddled with half-hearted appearances in material that’s beneath him.

At the same time, Insomnia boasts Williams’ third truly dark portrayal in a trio of similar roles from 2002, preceded by Death to Smoochy and One Hour Photo. Casting Williams is a stroke of genius because, as viewers, we instantly associate the actor with lighter comedy material. We like him, and we want to like him. So, when Finch tries telling Dormer that he never intended to kill Kate, at first, we believe him, doubting our suspicions and our own protagonist’s judgment. A strung-out cop who plants evidence, Dormer seems like he could be capable of miscalculating Finch, or at least unduly “assigning guilt”—a talent at which Dormer prides himself. But there’s a crucial point where Finch calls Dormer one night to explain what happened between him and Kate, and his story is not only monstrous but presented as if no blame could ever be assigned, despite his obvious culpability. He’s a psycho whose temper is so clenched up inside him that he snaps and turns violent when pushed. Williams, reserved and internalized, is so effective because he transforms Finch into a monster who doesn’t quite yet realize what he is.

At the same time, Insomnia boasts Williams’ third truly dark portrayal in a trio of similar roles from 2002, preceded by Death to Smoochy and One Hour Photo. Casting Williams is a stroke of genius because, as viewers, we instantly associate the actor with lighter comedy material. We like him, and we want to like him. So, when Finch tries telling Dormer that he never intended to kill Kate, at first, we believe him, doubting our suspicions and our own protagonist’s judgment. A strung-out cop who plants evidence, Dormer seems like he could be capable of miscalculating Finch, or at least unduly “assigning guilt”—a talent at which Dormer prides himself. But there’s a crucial point where Finch calls Dormer one night to explain what happened between him and Kate, and his story is not only monstrous but presented as if no blame could ever be assigned, despite his obvious culpability. He’s a psycho whose temper is so clenched up inside him that he snaps and turns violent when pushed. Williams, reserved and internalized, is so effective because he transforms Finch into a monster who doesn’t quite yet realize what he is.

Shooting in British Columbia, Nolan’s production makes wonderful use of the surroundings. Wet roads, overcast skies, and that omnipresent fog look striking thanks to Wally Pfister’s pristine lensing. But this setting isn’t just scenery; it’s a crucial narrative metaphor that also provides the material with some thrilling chase sequences. The best of them occurs when Dormer first locates Finch. A chase heads from the killer’s apartment outside, and then across a procession of floating logs. Finch maneuvers them without so much as a stumble, but Dormer trips and falls into the water, and suddenly he’s trapped underneath like some horrific nightmare come true. Though Insomnia’s story is a morality tale in which guilt is the primary antagonist, as a filmmaker whose artistic ambitions are equaled by his capacity to entertain us, Nolan knows to end the film with a stunning shootout at a lake house, a vast body of water and mountains filling the backdrop, and a conclusion that’s as poignant as is it cathartic.

In the end, the film takes its most noirish turn when Dormer finds himself mortally wounded after he’s shot and killed Finch. The corrupt hero cannot survive—the film’s moral center will not allow it—while on the scene, naïve but noble cop Burr has a piece of evidence that could incriminate Dormer and stain his legacy. With his death looming, she moves to throw it into the lake to protect him, but he stops her, having finally accepted the treacherousness of his actions. Dormer refuses to condemn Burr to the same torturous remorse that has plagued him, and so he tells her to remain an honest cop, even if it brings him down. Dormer then drifts off, finally able to sleep. All at once, we realize how seemingly inconsequential a part Walter has played in this detective thriller, and that it wasn’t really “about” catching the bad guy. Certainly, those elements provide chills for the commercial moviegoing audience, but the substance of Nolan and screenwriter Hillary Seitz’s story feels rooted in Dormer’s moral dilemma.

Indeed, Insomnia reminds me of Roman Polanski’s revisionist noir Chinatown, in that both follow an investigator-hero besieged by a particular (and eponymous) state of mind, and both states are enabled by a local stigma, either directly or by reputation. Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes finally succumbs to a “Chinatown” syndrome in which the film’s almost impenetrable mystery has so many twists and turns that it renders his character incapable of seeing the bigger, corrupt, sordid picture—finally, he’s told to give up trying to make sense of it: “Forget about it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” Likewise, Dormer’s wakefulness equates to a taunting state of shame, perpetuated by Nighmute’s enduring midnight sun. His only way to escape himself, thus the figurative sleeplessness and uninterrupted daylight, is through death. When Dormer finally falls asleep in the end, he will never wake up, but he has finally accepted that which has driven the plot—his denial of his own true nature. In this, Nolan crafts an expertly balanced drama with a surprising emotional underpinning that transcends what it means to be a good detective thriller. And though Insomnia does not match the grandiosity of his later pictures, it should not be considered a lesser effort for its familiarity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review