Inside Out 2

By Brian Eggert |

Inside Out 2, the sequel to Pixar’s 2015 original, once again considers the human mind as a living machine overseen by a control room of emotion-based administrators. Pete Docter initially conceived Inside Out, one of the animation studio’s best, and his concept is a curious one, suggesting that a person lacks autonomy, even agency, over their life. Rather, the personified emotions operate our behavioral switchboard. At any moment, Sadness might pull a lever to cause their human to cry, or Anger might smash some buttons and prompt an outburst. These emotions work in a vast inner system, helping to develop their human’s personality by collecting orb-like memories and, occasionally, setting aside life-defining ones. But in this scenario, a person seems like nothing more than an empty automaton—a vessel overseen by a group of emotional controllers and other bureaucratic functionaries, all of whom vie for control based on their assigned roles, some more imperative than others. In a way, the idea borders on artificial intelligence, a computer-like mind not so much rooted in a free-thinking consciousness or sentience but dependent on the little people inputting stored data into our brains when it’s called upon.

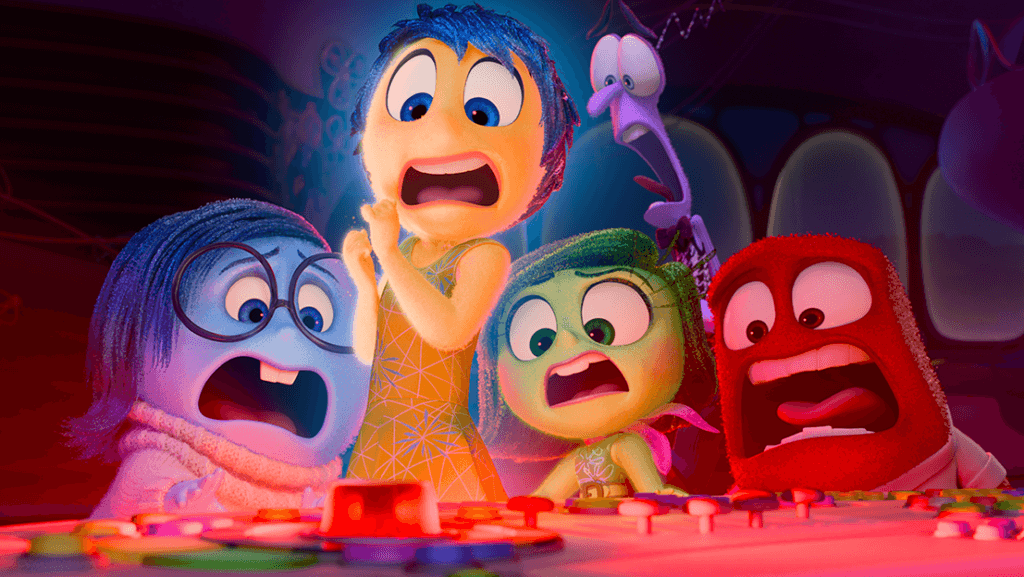

If the concept behind Inside Out implies that people are beholden to their emotions and memories, then the terrific sequel is about learning emotional intelligence. What exactly does that mean? Some people go their entire lives without figuring that out. In this context, it’s about not letting your emotions control you. That’s the lesson that Riley (Kensington Tallman), the young girl who, when she was 11, moved with her parents (Diane Lane, Kyle MacLachlan) from Minnesota to San Francisco and nearly lost herself to sadness. But she overcame that conflict in the original. When Inside Out 2 picks up, Riley is 13, and her puberty alarm signals major changes ahead. Her basic emotions—the ever-optimistic Joy (Amy Poehler), the fiery Anger (Lewis Black), the panicky Fear (Tony Hale), the social shield Disgust (Liza Lapira), and the frumpy Sadness (Phyllis Smith)—get some company. First to arrive: the frazzled Anxiety (Maya Hawke), followed by the wide-eyed and desirous Envy (Ayo Edebiri), the gentle giant Embarrassment (Paul Walter Hauser), and the ever-bored Ennui (Adèle Exarchopoulos).

As ever, Pixar’s collaborative animation and writing processes—the rare example of storytelling by committee that actually works—lead to some ingenious world-building, rich with detail and visual inventiveness. The screenplay by Meg LeFauve and Dave Holstein establishes new ideas about the inner workings of the adolescent mind, some inspired, some irresistibly on the nose. Pun-centric notions such as a “Sar-Chasm” (a mocking gorge) or a “Brain Storm” (a shower of light bulbs, each representing an idea) may seem obvious, except they result in amusing visualizations of abstract concepts—which, after all, is what Inside Out is all about. This time, Riley’s personality islands (Goofball Island, Friendship Island, Family Island, et al.) are less central than core beliefs, which stem from particularly impactful memories. In a subbasement of Riley’s mind that resembles the Tree of Souls from Avatar (2009), belief strings rise to form a personality nucleus: Riley’s sense of self. The original emotions, guided by Joy, have attempted to steer those core beliefs into positives, supporting Riley’s sense that “I am a good person.” Joy has even tried to suppress bad memories by ejecting them into the back of Riley’s mind, ensuring that their girl is wholesome and good-hearted.

The narrative unfolds around a three-day hockey camp, where Riley and her two friends, Grace (Grace Lu) and Bree (Sumayyah Nuriddin-Green), face tryouts for the high school team. But the weekend is thrown out of whack, not only by the arrival of puberty and, with it, an ultra-sensitive emotional switchboard, but also by Grace and Bree confessing that they won’t be going to the same high school as Riley. So Riley feels her future depends on making the team and becoming friends with Val (Lilimar), the school’s resident hockey star—at least, that’s what Anxiety and Envy make her believe. And they believe this to such an extent that the initial, simplistic emotions only get in the way. Following a series of elaborate projections about Riley’s future, Anxiety takes over, bottles up the old crew, ditches Riley’s core beliefs, and focuses all her frantic energies on these goals, no matter the cost. Joy and the others attempt to regain control, setting out once again in the expansive corridors of Riley’s mind to locate and restore her former sense of self. Meanwhile, Anxiety causes Riley to change everything about herself to succeed in the long run, to make Riley who she needs to be, even while denying who she is.

The narrative unfolds around a three-day hockey camp, where Riley and her two friends, Grace (Grace Lu) and Bree (Sumayyah Nuriddin-Green), face tryouts for the high school team. But the weekend is thrown out of whack, not only by the arrival of puberty and, with it, an ultra-sensitive emotional switchboard, but also by Grace and Bree confessing that they won’t be going to the same high school as Riley. So Riley feels her future depends on making the team and becoming friends with Val (Lilimar), the school’s resident hockey star—at least, that’s what Anxiety and Envy make her believe. And they believe this to such an extent that the initial, simplistic emotions only get in the way. Following a series of elaborate projections about Riley’s future, Anxiety takes over, bottles up the old crew, ditches Riley’s core beliefs, and focuses all her frantic energies on these goals, no matter the cost. Joy and the others attempt to regain control, setting out once again in the expansive corridors of Riley’s mind to locate and restore her former sense of self. Meanwhile, Anxiety causes Riley to change everything about herself to succeed in the long run, to make Riley who she needs to be, even while denying who she is.

Directed by Kelsey Mann, who has spent over a decade as part of Pixar’s story and creative teams, Inside Out 2 looks gorgeous, reminding us why this studio remains unchallenged as today’s top digital animation house. Several incredible sequences inside Riley’s mind explore imaginative ideas with visual brilliance and humor. One scene finds Joy and company locked in a vault, along with Riley’s darkest secret, a video game character she crushes on, and a riotous Blue’s Clues-esque character named Bloofy (Ron Funches), who talks to the screen. In a playful break from computer animation, Bloofy and his accompanying googly-eyed satchel appear in a hand-drawn animated style, while another sequence features a crude construction paper style—like something Trey Parker and Matt Stone would have made when they were 6. Elsewhere, the strange nooks and crannies across the landscape of Riley’s mind are visualized to splendid effect, if cartoonish by design. By contrast, the sequences involving Riley at the hockey camp stand out, giving viewers the sense that Pixar can go photo-real anytime they want, but they choose to work in this expressive style.

Still, with the introduction of four new emotion characters, Inside Out 2 prompts questions about the original. For instance, if Anxiety, Envy, Ennui, and Embarrassment emerge in puberty, why didn’t we see them when the 2015 film flashes into Riley’s parents’ heads? Instead, the parents seem to be operated by the same five basic emotions as Riley, with no trace of other dimensions. They pop up in the parents’ heads here momentarily in a kind of retroactive continuity, but otherwise, Riley’s parents apparently mastered these four emotions and effectively suppressed them. (They must be supremely well-adjusted since this writer’s mind is still plagued by them regularly.) And since I’m on the subject, it’s never made sense to me why the emotions in other people’s heads take on their host’s characteristics. Riley’s father has a mustache, so his emotions have mustaches, too. Similar parallels appear in Riley’s mother’s and her friends’ heads. From an animation perspective, I understand the choice—to differentiate others’ emotions from Riley’s. But it makes little sense in terms of consistent character design. In this elaborately conceived world, it’s one of the few details that remains a head-scratcher. But then, these are mostly nitpicks and questions that hardly spoil this genuinely moving and thoroughly entertaining experience.

Inside Out 2 will feel relatable for anyone who’s experienced anxiety (hand raised), particularly the extreme sort that can lead to a full-fledged attack. But more than the sequel’s anxiety-centric conflict, Pixar’s film is a testament to the many complexities, inconsistencies, impulses, desires, and emotions vying for control over who we are. It reminds us that our emotions don’t always have our best interests in mind and that our personalities can be multifaceted, even contradictory, from one day to the next. And that’s okay. Ultimately, it’s a film that proves my earlier “empty automaton” theory false by demonstrating that, with any luck, at some point in life, you stop letting your emotions control you, and you learn to call on certain emotions when you need them. It’s a resonant, profoundly fulfilling piece of work that captures the relatable drama of how a flurry of emotions emerges in teendom, yet these rather impulsive feelings never go away; we just learn to manage them better, rather than them managing us. (Again, this lesson contradicts what we know of Riley’s parents, who cling to their essential five emotions, which, even into adulthood, still drive their personalities.) Quibbles aside, Inside Out 2 is a sequel that, like the best of them, deepens and enriches the original in vital ways, while reminding audiences why, outside of Studio Ghibli, no one does animation quite like Pixar.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review