Inside Out

By Brian Eggert |

Ever feel conflicted or behave in a way you normally wouldn’t? Maybe you even hear the voices in your head arguing about what to do next or how to react in a particular situation. And if those voices belonged to actual functionaries within the complex metropolis of your mind, what would they look like? Traditionally, an angel sits on one shoulder and a devil on the other, and together they personify our conscience. But the human mind is much more complicated than a basic good-evil dichotomy. Everyone is a sum of their experiences, memory, and basic (and often not-so-basic) emotions. Such conceptual thoughts are the material of Inside Out, a marvelous animated film that exists almost entirely within the theoretical space inside our heads, operating by abstract rules and an uncanny understanding of human emotion. Returning to form, Pixar Animation Studios explores the high-concept notion of our inner voices in director Pete Docter’s (Monsters, Inc., Up) new film, and delivers one of their most inventive, affecting releases.

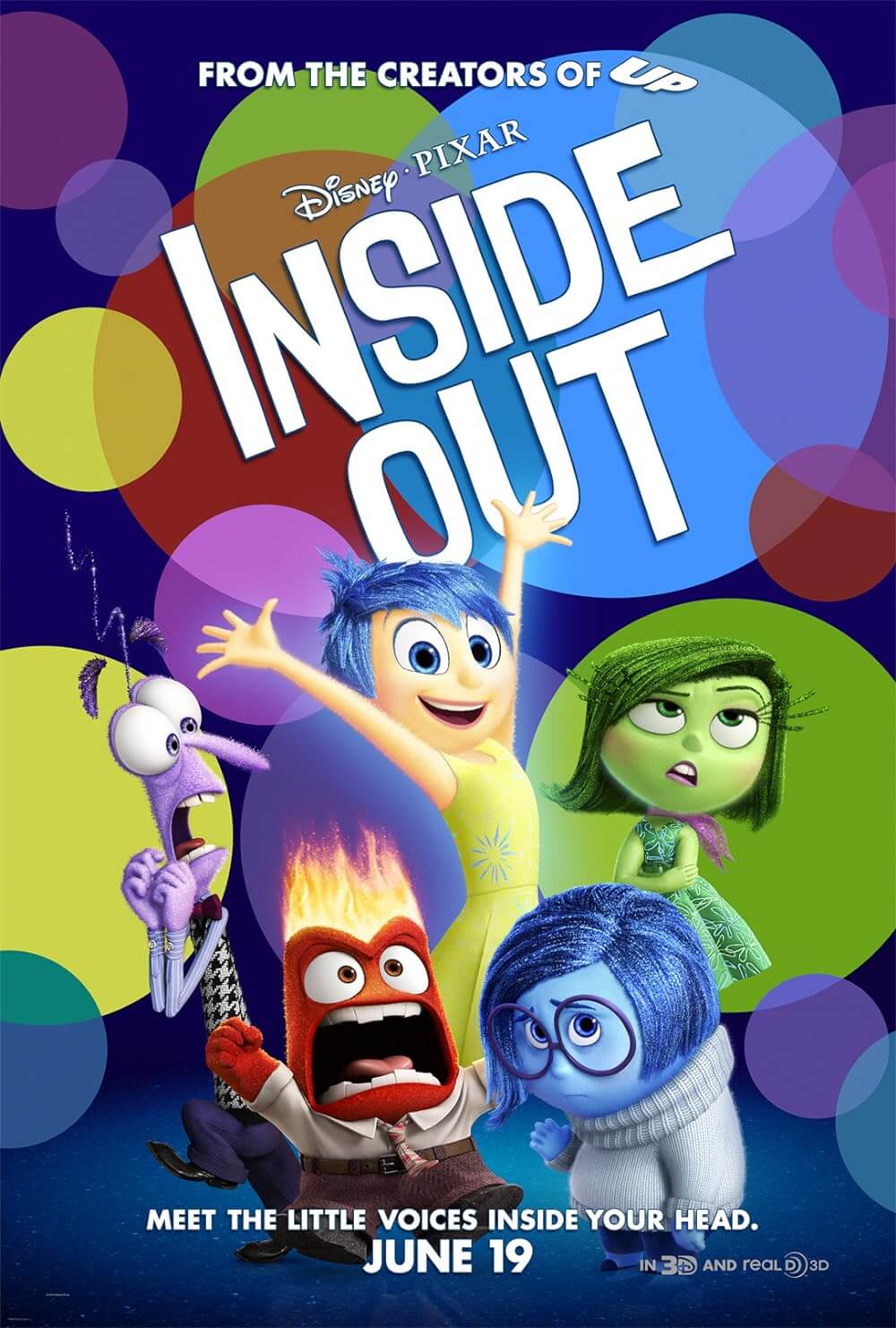

The story follows Riley (voiced by Kaitlyn Dias), a tomboyish 11-year-old girl who, along with her parents (Diane Lane and Kyle MacLachlan), moves from Minnesota to San Francisco. The move comes with no end of unexpected obstacles for Riley, including a long-delayed moving van, a difficult first day at school, a botched hockey tryout, and even the notion of running away. Although not much happens to Riley on the outside—beyond the not-inconsiderable stress of moving, of course—inside is another story. Within the mission control of Riley’s mind, her behavior and feelings are overseen by five central emotions: Joy (Amy Poehler), a yellow-glowing bundle of delight; Anger (Lewis Black), a boxy red fella with a fiery temper; Fear (Bill Hader), a purple, panicky master of probability; Disgust (Mindy Kaling), a green socialite; and Sadness (Phyllis Smith), a bespectacled sack of gloom. In Riley’s otherwise pleasant life, Joy commands her fellow emotions as a natural leader, glimmering with positive energy.

But Riley’s mind is a complicated network of departmental structures and libraries of memory. As any emotion may take over at any given moment, the dominant emotion creates a memory orb, each of which glow in the color of the emotion that created it. Hundreds are created every day. Five core memory orbs form Riley’s personality, represented by five islands or centers for her psyche: Family, Friendship, Honesty, Goofball, and Hockey. At her relatively young age, Riley’s psyche is somewhat uncomplicated and will grow more intricate in the future, establishing additional islands. For now, the move has made Sadness a little touchy, in that she’s been touching happy memories and transforming them into sad ones. For example, once-positive thoughts of Minnesota now become aching memories of better times. To counteract Sadness’ sudden contamination of memories, Joy, with Sadness behind her, heads out of the control room and into the wilds of Riley’s mind to set things straight and make Riley happy again. But then, this leaves Anger, Disgust, and Fear in control.

Not everything about Riley is encompassed by these five emotions, as Joy and Sadness soon learn. Outside of the control room, there’s a “train of thought” that appears as a locomotive chugging along on tracks, which appear before it and disappear behind it. Among long shelves of countless memory orbs, workers dispose of fading memories, dumping them into a vast abyss, never to be remembered again. These ingenious concepts and inventions have been articulated within the script by Docter, Meg LeFauve, and Josh Cooley, and visualized by the Pixar staff to wonderful effect. Among the most clever is Bing Bong (Richard Kind), Riley’s imaginary friend who leads Joy and Sadness into a chamber of abstract thought, where they’re broken down, piece by piece, into shapes, two dimensions, and finally, the impression of color. Elsewhere, Joy and Sadness step into Riley’s dream factory, a setup not unlike a movie studio lot; they also venture into her clown-infested unconscious, where her deepest fears are locked away. These ideas may sound complicated, but they’re explained in such a breezy, effortless way that the audience cannot help but instantly grasp them, and more importantly, identify with them.

Of course, Joy attempts to dominate every moment in the service of Riley, denying Sadness every opportunity to resolve the situation. This resourceful metaphor for repression plays out in an imaginative way that only Pixar could conceive, in a mental landscape informed by an 11-year-old mind. By holding up a positive front and denying one’s feelings, the mind becomes a conflicted and crushing place; and if maintained long enough, a person could fall apart. This insightful theme finds an entertaining way to tell viewers, young and old, how to acknowledge their emotions, pleasant or not. Typically unpleasant emotions can be helpful if expressed in the right way, just as positive emotions can be damaging if they deny authentic feelings. What better place to investigate this dynamic than in the confused head of a youngster? More than just exploring the personification of emotions and the inner workings of a mental state, the film also explores the strange and confusing time during the onset of adolescence. (As a result, we can’t help but imagine what an adulthood version of Inside Out might look like.)

Inside Out beautifully transforms emotional conflict into an adventure, a surreal look at the internal machinations that encompass why we feel the way we do. Meanwhile, tender scenes in the real world range from blissful to bittersweet, from tragic to downright devastating. Varying animation styles depict the two worlds as cartoonish and realistic, respectively. And yet, the material retains an accessible emotional center to which young children and adults will identify. Quite refreshingly, Inside Out does not limit its investigation of this concept to Riley. Brief glimpses into her parents’ minds offer a perceptive look at how the mind operates. Consider a funny bit where Riley’s mother remembers a hunky Latino man and, despite loving her husband, her Fear emotion hangs onto that memory, “Just in case.” Riley’s father is guided by a seemingly inept grouping of control room emotions. The best of these asides occurs during the end credits, where Docter takes us into the minds of an insecure teen, a moody pizza place clerk, and even pets (the look into a cat’s mind offers the film’s most gut-busting laugh).

Most impressive is Inside Out‘s embrace of sadness and melancholy as essential components of a person’s emotional growth. This represents a wholly unique perspective for an animated film, in that most cheery efforts from Dreamworks or Disney resolve to be escapist, bright, overly optimistic larks devoid of real emotional underpinnings. But this film recognizes the need for sadness as a necessity for self-understanding and empathy, for emotional development and maturation. Inside Out challenges the viewer with aching turns in the plot, putting us through the same wringer as Riley. Without sadness, there is no recognition of longing, no artistic yearning, no desire for self-exploration—and this is a film that demands self-exploration out of its audience, beginning with Riley, but lasting long after the film is over. It will change how you think about your feelings, and perhaps even recalibrate how you visualize what’s going on in your head. That Pixar has released a film acknowledging the need to be attuned to your emotional state is a bold testament to their sophistication, not only as an animation studio, but also as storytellers.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review