Inside Llewyn Davis

By Brian Eggert |

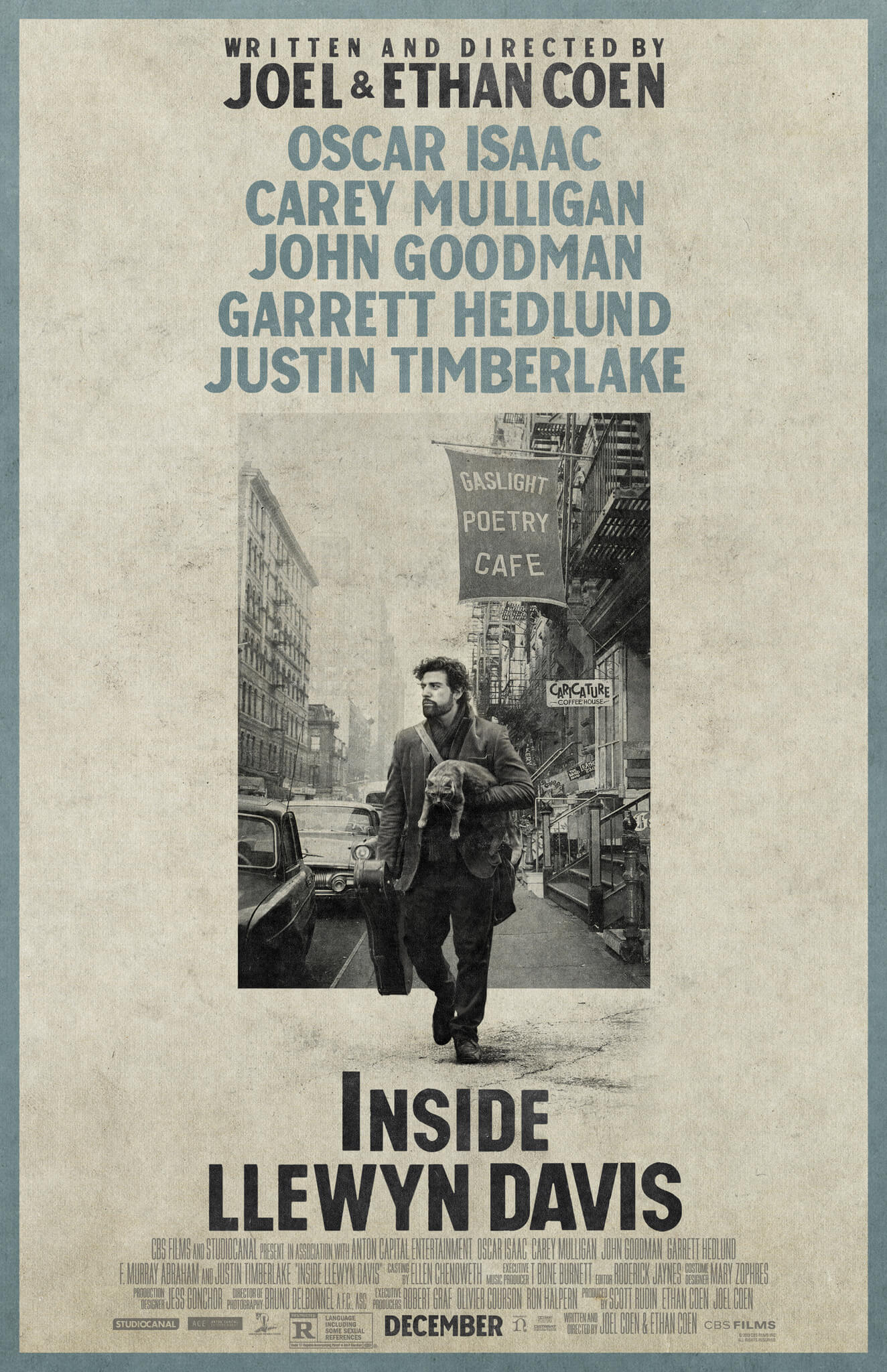

Joel and Ethan Coen’s Inside Llewyn Davis does not follow a straight-line narrative; as the title suggests, it settles within the eponymous anti-hero’s meandering existence. Set against the backdrop of the 1960s Greenwich Village folk music scene, this character study follows a starving artist type whose good, but not great, talent isn’t enough to transcend his deep character flaws. The film rambles through the bearded, springy-haired, tenor-voiced folk singer’s odyssey, a circular journey with moments of surrealism and Homeric allusion. When it arrives at its final destination, it does so with almost mythic proportions, landing in a familiar realm for the Coens, where their series of striving losers are fated to their own haplessness. Filled with darkly comic and cynical observations about its period and its soulful performer who, with no malice or intent, makes a mess of other people’s lives and his own, the film’s sharply observed tale is among the Coens’ most carefully crafted and elusive yet.

Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) first appears to us at the Gaslight, a basement club saturated in the atmosphere of cigarettes and espresso. After his ballad, he remarks, “If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.” The same could be said of folk tales, which Inside Llewyn Davis certainly is. The story finds Llewyn adrift without a coat during a cold New York City winter, moving about from one petty gig to another, crashing with friends when possible. Anguished over the death of his musical partner, Llewyn’s subsequent solo career has been slow, in part because he refuses to step outside his one man, one guitar approach, and takes himself far too seriously as an artist. His pretentiousness is only matched by his awful behavior. Llewyn is a despicable sort, his bad manners and self-absorbed nastiness almost making the character unsympathetic. Almost. He swears around his young nephew despite the protests of his sister (Jeanine Serralles), and with his misplaced artistic integrity, he disrupts a chummy dinner party at the home of his achingly nice friends, the Gorfeins (Ethan Phillips, Robin Barrett).

The character of Llewyn Davis was inspired by the “Mayor of MacDougal Street” himself, Dave Van Ronk, an acoustic folk singer on the Greenwich Village circuit. Van Ronk left a greater legacy behind him than Llewyn Davis ever could, and the Coens’ film will undoubtedly bring the singer’s music back into mainstream view, if only for as long as Inside Llewin Davis remains in the spotlight. Indeed, the film’s album cover “Inside Llewyn Davis” is a mockup of the 1963 release “Inside Dave Van Ronk”, but the similarities don’t go much further than the surface. Llewyn Davis is a pure Coen Brothers creation. But in other ways, the Coens’ story feels inspired by Bob Dylan, or rather Dylan is who Llewyn Davis could have become had he just a little more talent and fewer hang-ups. Dylan, too, broke out in the Greenwich folk scene, and he mirrors the Coens in that they’re all Jewish, Minnesota-born artists whose output resists interpretation yet demands investigation. Their art is both reflective of what came before them and somehow completely original.

Steeped in the milieu of Greenwich Village, Inside Llewyn Davis isn’t about folk music or even about the extreme political setting of the 1960s per se; rather, it’s another of the Coens’ meditations on a besieged schmuck who authors his own cruel fate. Through the course of the film, Llewyn is accompanied by a spritely orange tabby cat, whose fate may be the cause of dissent among certain animal lovers in the audience. He carries it around with him like a loyal companion, but the loyalty becomes an illusion when the cat runs off. This false allegiance applies to his friends too. “You’re like King Midas’ idiot brother,” says his friend Jean (Carey Mulligan), “Everything you touch turns to shit.” Llewyn may have impregnated Jean; and though the pregnancy may also belong to her husband and singing partner Jim (Justin Timberlake), the prospect that it could be Llewyn’s is enough to inspire an abortion. He has no argument; this has happened before with other women. If Llewyn has any purpose in life, it’s not children—it’s show business. Everyone else just “exists,” he explains.

Steeped in the milieu of Greenwich Village, Inside Llewyn Davis isn’t about folk music or even about the extreme political setting of the 1960s per se; rather, it’s another of the Coens’ meditations on a besieged schmuck who authors his own cruel fate. Through the course of the film, Llewyn is accompanied by a spritely orange tabby cat, whose fate may be the cause of dissent among certain animal lovers in the audience. He carries it around with him like a loyal companion, but the loyalty becomes an illusion when the cat runs off. This false allegiance applies to his friends too. “You’re like King Midas’ idiot brother,” says his friend Jean (Carey Mulligan), “Everything you touch turns to shit.” Llewyn may have impregnated Jean; and though the pregnancy may also belong to her husband and singing partner Jim (Justin Timberlake), the prospect that it could be Llewyn’s is enough to inspire an abortion. He has no argument; this has happened before with other women. If Llewyn has any purpose in life, it’s not children—it’s show business. Everyone else just “exists,” he explains.

Once a significant character’s name is revealed to be Ulysses, whose story in Homer’s The Odyssey inspired the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the viewer gathers a sense of why Llewyn wanders, mooching and occupying his friends’ couches for the night, or traveling deep into the underworld on a road trip to Chicago. He’s a stray cat and a Homeric hero all at once, making the rounds through his friends for a warm bed and a free meal, ever deficient in self-awareness and beleaguered by his merciless, self-perpetuated bad luck. He faces a series of grotesque characters of true Coen Brothers style, such as John Goodman’s crusty jazzman or Adam Driver’s Jewish urban cowboy. After Llewyn sings a fine rendition of “The Death of Queen Jane” at the Gate of Horn club for owner Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham), his work is assessed in a single statement: “I don’t see a lot of money here.” Homer wrote about gates of horn and ivory when Odysseus’ wife Penelope dreamt of a false premonition of her husband’s return. The gate of ivory was a deception, but the gate of horn is a place where the truth is told. Nevertheless, Llewyn carries on, unable to break out of his bumming around, not even to rejoin the merchant marines and give up his career as a musician.

Character actor Isaac plays both Llewyn and the guitar in a brilliant performance that requires him to sing tragic ballads, like “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” and “Shoals of Herring”, and he does so with just enough talent to make the character’s struggle for success a tragic example of the human condition. The Coens’ collaborator and music supervisor T Bone Burnett produces what must be the best soundtrack of 2013, the songs aching with pained lyrics to reflect the characters and the times, each of the songs performed by the actors singing them in the film. Production designer Jess Gonchor also brings to life the airs of Greenwich Village, Queens, and Chicago of the period, all speckled with careful details particular to the 1960s scenery. Though the Coens’ longtime cinematographer Roger Deakins isn’t behind the camera here, Bruno Delbonnel (Amélie, Across the Universe) creates a wonderful balance between the realistic and the soft-filtered haze of Llewyn’s rather piteous existence.

The Coens have always been more interested in failure than success, losers over winners, and stupidity more than smarts. They concern themselves with unsolvable existential dilemmas and the meaninglessness of life or any attempt to understand it. Viewers often leave a Coen Brothers film wondering, “What does it all mean?” even though they were thoroughly entertained. Inside Llewyn Davis occupies a structure reminiscent of A Serious Man, where Michael Stuhlbarg’s Larry Gopnik asks endless questions; but the answers he receives are either cryptic, utter nonsense, or altogether tragic. Or perhaps the film is better likened to their 1991 Palme d’Or winner Barton Fink, wherein John Turturro is a successful playwright who ventures to become a Hollywood screenwriter but suffers from debilitating writer’s block. These three pictures make a tidy thematic trilogy about individuals, all professionals and seemingly experts in their chosen craft, plagued by their own futile search for meaning where none exists.

The Coens have always been more interested in failure than success, losers over winners, and stupidity more than smarts. They concern themselves with unsolvable existential dilemmas and the meaninglessness of life or any attempt to understand it. Viewers often leave a Coen Brothers film wondering, “What does it all mean?” even though they were thoroughly entertained. Inside Llewyn Davis occupies a structure reminiscent of A Serious Man, where Michael Stuhlbarg’s Larry Gopnik asks endless questions; but the answers he receives are either cryptic, utter nonsense, or altogether tragic. Or perhaps the film is better likened to their 1991 Palme d’Or winner Barton Fink, wherein John Turturro is a successful playwright who ventures to become a Hollywood screenwriter but suffers from debilitating writer’s block. These three pictures make a tidy thematic trilogy about individuals, all professionals and seemingly experts in their chosen craft, plagued by their own futile search for meaning where none exists.

There’s a scene shown near the beginning of the film and, like clockwork, seen again at the end. A bartender sends Llewyn to an alleyway behind the Gaslight to meet a suited “friend”. In the shadows is a rugged-voiced southerner who socks Llewyn in the face and kicks him when he’s down—punishment for heckling a performer on the stage. Significant not only for Llewyn’s ill-tolerance for other artforms but the scene’s looping quality, the sequence encapsulates the mystique inherent to the Coens’ cyclic approach. At first, Llewyn appears to be the victim of a random beating; the second time around, it’s a well-deserved thrashing and another in a long succession of self-perpetuated punishments. Inside Llewyn Davis is a fascinating exploration in this regard, allowing the audience to consider, and then re-consider the character after we’ve become versed in his pattern of behavior. Though we may not particularly like Llewyn Davis, we understand him, his ambition, and his failure, and we cannot help but feel something profound toward his tale of melancholy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review