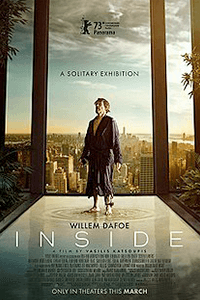

Inside

By Brian Eggert |

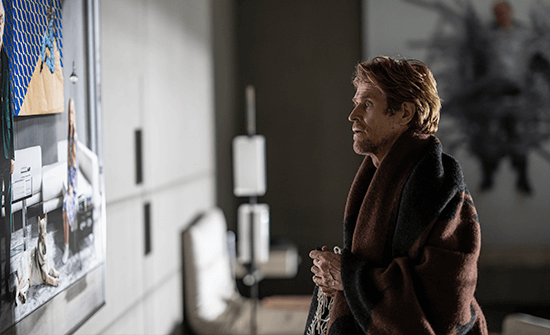

Inside is a psychological thriller that weighs the value of art. Willem Dafoe stars as Nemo, a professional art thief who breaches a stylish penthouse in the first sequence to steal several high-value pieces. The minimalist, museum-like aesthetics of the apartment have a severe appearance, and though luxurious, it doesn’t look like a living space. To be sure, it becomes Nemo’s prison when the state-of-the-art security system doesn’t behave according to plan and goes into lockdown mode, leaving him trapped indefinitely. Worse, the technologically advanced apartment seems designed to capture and contain intruders. Over the following hours, days, and even weeks, the thief must endeavor to escape, surrounded by millions in contemporary artworks. While the logistics of Nemo’s situation don’t always make practical sense, the film, directed by Greek helmer Vasilis Katsoupis, raises questions about how art can become a driving force for life. Is it merely a commodity to be bought, sold, or stolen? Does it give life purpose beyond the bare necessities? And what meaning does art—or humanity, for that matter—have when it’s locked away in private collections?

These questions become peripheral to Nemo’s moment-by-moment situation. Almost immediately, his circumstances become dire. The windows prove unbreakable and the door impenetrable. The toilet doesn’t flush. There’s no running water. The refrigerator has a few scraps of food and a door that, when left open, plays “Macarena” (after a similar needle drop in last year’s Aftersun, let’s hope Los Del Río’s ’90s hit isn’t making a comeback). However, the walls feature some stunning pieces, including a work by Francesco Clemente and a coveted self-portrait of Egon Schiele. Still, it’s worth asking why authorities never arrive after the alarm sounds. The owner has tropical fish, but no one shows up to feed them. Was the penthouse owner notified that the alarm went off? If so, we never find out. All the while, we cannot help but wonder whether the excessively wealthy inhabitant of this apartment has arranged all this, perhaps to document the fallout in a kind of living installation. Note also how the heat rises to a sweltering 100 degrees Fahrenheit, but then days later, it drops to near freezing. Is this the result of a broken thermostat or the penthouse owner torturing his intruder-turned-captive? Alas, there’s no such twist or explanation.

Instead, the viewer watches Dafoe in a hypnotic performance, exploring every corner of the penthouse to escape and survive—all while under physical and existential torment. Almost devoid of dialogue and entirely focused on the actor, apart from a couple of dream sequences and some people spied on security camera footage, the film’s 105-minute runtime passes swiftly. That’s surprising, given how the concept could have been a plodding endurance test. But there’s a strangely fascinating quality to watching Dafoe build a structure out of furniture and shelves to reach a skylight some twenty feet up, only to discover he doesn’t have the tools to unfasten the fixture. Few actors have the presence to command an entire film on their own like this, and Dafoe is uniquely suited to stories about isolation, interiority, and psychological decline—see Antichrist (2009) or The Lighthouse (2019). So when he starts to hallucinate and see himself in a painting, it feels like familiar territory for the actor in the best way imaginable.

Despite Dafoe as the headliner, Inside might qualify for categorization in the Greek Weird Wave, given its Greek production company and predominantly Greek crew. Although the film never reaches the bizarre quality found in the cinemas of Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari, it borders on surreal and occasionally grotesque (evidenced in Nemo’s solution for a toilet and later exploration of dog food). Greek Weird Wave films tend to confront structures of authority, usually within the family or relationships, but Katsoupis aims his film at how society values art. According to the press notes, Katsoupis conceived his dramatic feature debut while making his documentary, My Friend Larry Gus (2015). He was staying in a posh Manhattan apartment, not unlike the one in Inside, and began to wonder at what point art loses its value, if ever. Whatever the impetus, screenwriter Ben Hopkins, who developed the script from Katsoupis’ initial idea, seems less interested in the story’s conceptual origins than Nemo’s situational concerns.

Despite Dafoe as the headliner, Inside might qualify for categorization in the Greek Weird Wave, given its Greek production company and predominantly Greek crew. Although the film never reaches the bizarre quality found in the cinemas of Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari, it borders on surreal and occasionally grotesque (evidenced in Nemo’s solution for a toilet and later exploration of dog food). Greek Weird Wave films tend to confront structures of authority, usually within the family or relationships, but Katsoupis aims his film at how society values art. According to the press notes, Katsoupis conceived his dramatic feature debut while making his documentary, My Friend Larry Gus (2015). He was staying in a posh Manhattan apartment, not unlike the one in Inside, and began to wonder at what point art loses its value, if ever. Whatever the impetus, screenwriter Ben Hopkins, who developed the script from Katsoupis’ initial idea, seems less interested in the story’s conceptual origins than Nemo’s situational concerns.

Unfortunately, Katsoupis and Hopkins engage in heavy-handed symbolism along the way, such as Nemo’s interest in the fish trapped in a tank or the wounded pigeon just outside the window whose journey matches his for much of the movie. Unable to escape, the bird eventually starves, becoming a rotting pile of maggot food. Nemo fares better, but to what degree remains open to interpretation. It’s unclear whether the character grows, and if so, why and how. He spends a questionable amount of time not trying to escape. For instance, what does Nemo’s fleeting interest in the closed-circuit security monitors, specifically a maid he names Jasmine (Eliza Stuyck), have to do with anything—aside from taunting Nemo and driving him ever more insane from loneliness? And besides looking at the artworks on display, he also creates sketches in a notebook and murals on the walls, including a portal-like abyss, as he proclaims there’s “no creation without destruction.”

Inside is a sharp-looking film thanks to production designer Thorsten Sabel’s austere spaces—inhabited by a careful selection of artworks curated by Leonardo Bigazzi, complete with original pieces commissioned for the film. Similar to the receding white spaces of museum walls that emphasize the featured art, the penthouse’s almost brutalist gray walls, a video installation room, and furniture (which looks more staged than comfortable) remind us that art exhibition is a philosophy unto itself. Steven Annis’ cinematography looks crisp and assured, but editor Lambis Haralambidis doesn’t allow for a clear understanding of the penthouse’s internal geography, perhaps for an intentionally disorienting effect. Meanwhile, Dafoe’s wiry body, a thin flesh stretched over a skeletal frame, contrasts the chilly surroundings. That is, until he starts to resemble one of Schiele’s portraits. While Nemo gradually tears down the penthouse interior and turns the space into a ramshackle container, Dafoe becomes one with the space as he deteriorates.

In the bookend narration, Nemo twice recounts a memory from childhood when a teacher asked the class a question. What three things would they take with them if their house was on fire? Nemo recalls his answer: his cat, an AC/DC album, and sketchbook. Then he observes, “Cats die, music fades, but art is for keeps.” Setting aside that music—even AC/DC—is also art, the story brings to mind last year’s The Banshees of Inisherin, which asked similar questions about the legacy people leave behind with art and whether that’s important next to everyday existence. Inside contemplates these ideas with obvious symbolism to spare, and Katsoupis and Hopkins don’t integrate the themes into the text in a way that satisfies or leaves one feverishly ponderous afterward. For much of the runtime, the viewer is concerned foremost with Nemo’s escape and survival, whereas the art commentary remains an afterthought. Intriguing, but more successful as a survival thriller than a lofty intellectual exercise, the film will make a fine discussion prompt for college courses on aesthetic theory.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review