Inherent Vice

By Brian Eggert |

In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Orson Welles remarked on the complicated scenario of The Big Sleep, Howard Hawks’ adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s twisting murder mystery, saying, “I keep holding it against [Hawks] because I couldn’t follow the plot.” Bogdanovich replied, “Sometimes the rhythm of your scenes is so exciting I don’t really care what they’re saying—it becomes like listening to music.” In this sense, listening to Paul Thomas Anderson’s labyrinthine detective story Inherent Vice is like grooving to a song by The Doors, a drug-fuelled kaleidoscope of circus notes, deep guitars, and poetic lyrics, layered altogether in an entertaining and moody assemblage. If Welles were alive today, he might have the same observations about Anderson’s plotting, a maze of corruption and murder closely following Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel of the same name. Set in California’s counterculture beach towns in the 1970s, the comic noir is a persistent whodunit through which closing the case is less significant than the experience of seeing through a fogged perspective.

Much like his Boogie Nights or more recently The Master, Anderson’s film centers on a group of wanderers and displaced types searching for something—though what it is they do not always know. Like those films, Inherent Vice takes place against a tumultuous period backdrop: here it’s 1970, in the surf houses and hippie shacks of Gordita Beach, California, a fictional South Bay town based on Manhattan Beach, at a time not yet fervent with Vietnam War protests, yet fuelled by Nixon era and post-Manson Family Massacre paranoia (where “Any gathering of three or more civilians is considered a possible cult,” says a cop). Drug culture has reached a peak; marijuana flows freely, some cocaine too, but there’s a pervasive stigma around heroin. As Pynchon writes and Anderson’s script sharply observes, “As long as American life was something to be escaped from, the cartel would always be assured a bottomless pool of new customers.” These environs are the home of Larry “Doc” Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix, under thick sideburns and a mop of messy hair), a private investigator operating out of a doctor’s office (his secretary, played by Anderson’s partner Maya Rudolph, even sports a nurse’s getup).

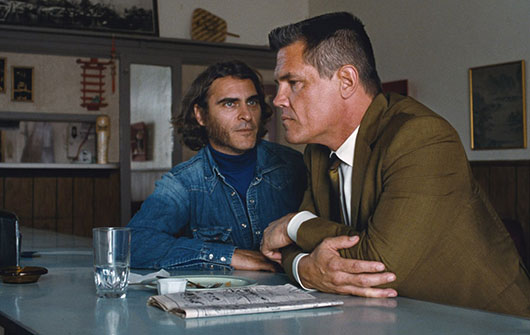

Over the course of a complex mystery involving several ongoing cases, Doc’s story begins when Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston, daughter of Sam), an ex-girlfriend for whom he still carries a torch, arrives out of the blue and asks for help. Her teary-eyed concern involves her current beau, slick land developer Mickey Woldmann (Eric Roberts), whose duplicitous English wife, and her lover, scheme to land Mickey in the looney bin to assume his riches for themselves, and they want Shasta’s help to carry out their plan. But then Shasta disappears, and soon after so does Mickey. When Doc follows up on one of Mickey’s land deals, he ends up thumped on the noggin at Chick Planet, a sex parlor, only to awake alongside the corpse of one of Mickey’s bodyguards—one of many members of an Aryan biker gang. Doc has been made a suspect in his own case, but by whom? The detective investigating, blowhard Det. Christian “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin), makes his disdain for hippies well known. He’s not opposed to beating Doc, in slow-motion no less, nor is this complex character opposed to sharing case notes with our well-baked hero.

Over the course of a complex mystery involving several ongoing cases, Doc’s story begins when Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston, daughter of Sam), an ex-girlfriend for whom he still carries a torch, arrives out of the blue and asks for help. Her teary-eyed concern involves her current beau, slick land developer Mickey Woldmann (Eric Roberts), whose duplicitous English wife, and her lover, scheme to land Mickey in the looney bin to assume his riches for themselves, and they want Shasta’s help to carry out their plan. But then Shasta disappears, and soon after so does Mickey. When Doc follows up on one of Mickey’s land deals, he ends up thumped on the noggin at Chick Planet, a sex parlor, only to awake alongside the corpse of one of Mickey’s bodyguards—one of many members of an Aryan biker gang. Doc has been made a suspect in his own case, but by whom? The detective investigating, blowhard Det. Christian “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin), makes his disdain for hippies well known. He’s not opposed to beating Doc, in slow-motion no less, nor is this complex character opposed to sharing case notes with our well-baked hero.

In another unrelated case that, of course, turns out to be closely related to the larger case, former junkie Hope Harlingen (Jena Malone) hires Doc to find her husband, Coy (Owen Wilson), a sax player who’s missing, serves as an informant for various government agencies and is undoubtedly associated with the wrong crowd. Drifting in and out of Doc’s ongoing case are smaller players whose roles are more like impressions through the smoke: Doc’s sometime-girlfriend Penny (Reese Witherspoon) works for the District Attorney’s office but swings by Doc’s late at night for a pizza; black-power ex-con Tariq Khalil (Michael K. Williams) sets Doc in motion to investigate Mickey’s skinhead bodyguards; former teen runaway Japonica (Sasha Pieterse) now shacks up with a coke-crazed dentist Dr. Blatnoyd (Martin Short), who may be a player in a tax-shelter turned crime syndicate; Doc occasionally meets with his maritime lawyer Sauncho Smilax, played by Benicio del Toro (in one side-splitting scene, they order some greasy food together and their waitress tells them “You’re going to want to get good and fucked up before this meal”); and working girl Jade (Hong Chau) warns Doc to stay away from the Golden Fang, whatever that means.

Keeping things straight, sort of, Doc’s astrologer friend Sortilege (singer-songwriter Joanna Newsom) provides narration from an impossibly omnipotent station, but an omnipotent astrologer is about as unreliable a narrator as you can get. She might be an onscreen stand-in for Pynchon’s prose, or perhaps a voice inside of Doc’s head, but she provides hindsight commentary on the events and Doc’s impressions thereof. But Doc’s under-the-influence outlook sometimes muddles our understanding of how the mystery continues to unfold. Identities shift, and the audience can never be sure if Doc’s ever-running paranoia fuels the change or if the mystery before us is truly so involved. Take Coy, who might be dead, might be an informant, or might be a prisoner of a cult; either way, Coy later admits about his fellow band-mates, “Even when I was alive, they didn’t know it was me.” Or consider the Golden Fang, which according to Sauncho is a boat that imports pure heroin; it might also be a gold-tipped building run by a conglomerate of dentists; but maybe it’s one of Mickey’s bodyguards who bites one character to death—Doc wants Bigfoot to check the forensic report for traces of gold in the bite wound. When your mind has been expanded by a steady course of drugs, the possibilities are endless.

Pynchon’s dialogue-driven book of interweaving characters serves Anderson well; the director’s proclivity for mosaic pieces follows his adoration for the works of Robert Altman—an esteem so pronounced that when Altman’s health was failing, he called upon Anderson to finish scenes of A Prairie Home Companion for him. And while Inherent Vice also has much in common with Roman Polanski’s Chinatown and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves as a structural mystery, wherein a small case leads to a conspiratorial cover-up, perhaps a better comparison is Altman’s The Long Goodbye, his Chandler-based mystery set within its 1973 environs. In that film, Elliott Gould also sought out a missing man with an English wife, and like Doc, he searched in California beachside houses and even a mental institution of sorts. Both Altman’s film and Anderson’s probe a mystery that’s spun so out of control it requires someone with Doc’s knack for alternate thinking methods to solve. Given its particular approach to tracing a mystery, Anderson’s film has more in common with the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski, which was their version of a Chandler yarn, only solved by Jeff Bridges’ pot-smoking layabout The Dude.

Even if the plot’s machinations elude us, Inherent Vice features at least two outstanding lead performances, first from Phoenix, and second from Brolin. The exercise of watching Phoenix disappear into a buzzed performance is about noticing his subtle, often hilarious reactions of amusement, bewilderment, concern, and paranoia, each off-kilter compared to how another PI in his position might behave, and each carefully understated with a touch of something more. Those touches come through most often opposite Brolin’s flat-topped, pseudo-celebrity detective. Bigfoot turns his police work into a vague star status, appearing in an afro on a low-rent TV commercial, or as background dressing on an episode of Jack Webb’s Adam-12. He’s a huge ego and self-proclaimed “walking civil rights violation” who also has shades of vulnerability. Brolin bolsters when Bigfoot shouts his order for more Swedish pancakes at an Asian diner, but he appears utterly defeated in a scene at home, where he remains seated while his wife (who appears only from the shoulders-down, like the adults in cartoons from Tom and Jerry to Muppet Babies) commandeers his phone call with Doc as if taking a toy away from a child. A man with such control issues is bound to break down, and when he does, both Phoenix and Brolin transcend the material with their delivery in a strangely poignant scene near the end.

Cinematographer Robert Elswit shoots in beautiful 35mm, uncleaned by artificial digital filters that would otherwise remove dirt and scratches, leaving the film with a pointedly 1970s look. Elswit, who has shot every Anderson film since Hard Eight and won an Oscar for There Will Be Blood, uses a visual style less concerned with the elaborate, fluid camerawork demonstrated in Anderson’s Boogie Nights and Magnolia, but more attuned to Doc’s dope habit—mellow and wary, a style captured in several medium shots that slowly move inward to close and suspicious proximity. Several of the most intense encounters proceed this way, all in their own very long, deliberate takes (like the sequence where Shasta arrives at Doc’s place, completely disrobes, and talks him into a complex sex scene that ends with “This doesn’t mean we’re back together”). Elswit’s textured lensing creates a hallucinatory sense behind several sequences that perfectly align with Doc. At the same time, Jonny Greenwood’s score accompanies the varied tones of humor and suspicion with a pairing of twangy, playful melodies and ominous thriller tempos.

Cinematographer Robert Elswit shoots in beautiful 35mm, uncleaned by artificial digital filters that would otherwise remove dirt and scratches, leaving the film with a pointedly 1970s look. Elswit, who has shot every Anderson film since Hard Eight and won an Oscar for There Will Be Blood, uses a visual style less concerned with the elaborate, fluid camerawork demonstrated in Anderson’s Boogie Nights and Magnolia, but more attuned to Doc’s dope habit—mellow and wary, a style captured in several medium shots that slowly move inward to close and suspicious proximity. Several of the most intense encounters proceed this way, all in their own very long, deliberate takes (like the sequence where Shasta arrives at Doc’s place, completely disrobes, and talks him into a complex sex scene that ends with “This doesn’t mean we’re back together”). Elswit’s textured lensing creates a hallucinatory sense behind several sequences that perfectly align with Doc. At the same time, Jonny Greenwood’s score accompanies the varied tones of humor and suspicion with a pairing of twangy, playful melodies and ominous thriller tempos.

There’s an audience that might enjoy Inherent Vice purely on the level of a stoner comedy, except it’s far too rich and cleverly made for such a one-note viewing—the 2-and-a-half hour runtime implies as much. There’s another segment of the audience that might look upon this film and expect a true-to-form film noir set in the 1970s, but then grow exasperated by how several of the subplots seem unresolved, and how the mystery never quite works through each and every strain. But then, some of those strains are imagined and later forgotten in Doc’s head, and so the film becomes less a tried-and-true mystery than an immersion into an adrift culture, performed so wonderfully by Anderson’s ensemble cast. The metaphor permeating through the picture is that the mystery is so exhaustive and deceptively head-spinning that only someone in Doc’s influenced state could possibly understand it, and even then, connections are made through a fog and a trace of puzzlement. Anderson’s film is brilliantly unique in its expectations of the viewer, in that it wants the viewer to experience it more than understand it, and the experience proves a hallucinatory, often hilarious, and fulfilling one as both entertainment and carefully constructed comic art.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review