Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

By Brian Eggert |

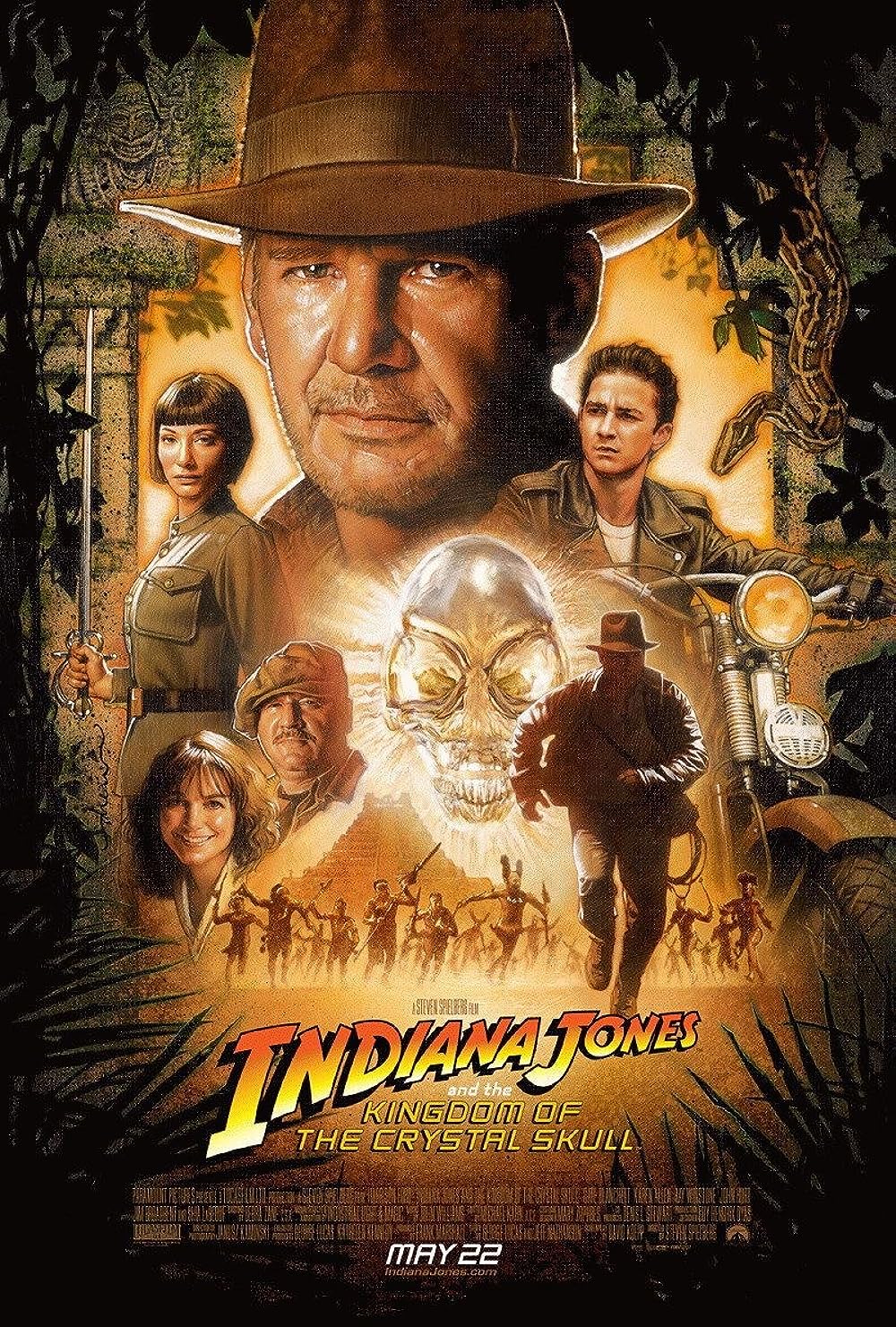

In the opening of Indiana Jones and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, one of the series’ most joyously outlandish action sequences launches the film’s ensuing adventure. Harrison Ford’s timeless hero finds himself captured by Russian spies and brought to top-secret Warehouse 51 in the Nevada desert. Sexy Soviet villainess Irina Spalko, played by Cate Blanchett, demands Indiana Jones lead her cadre through an endless depository of crated government secrets to find an intricate freezer casket. Inside is an alien corpse kept preserved since the Roswell UFO crash a decade earlier in 1947. Spalko wants the extraterrestrial’s magnetized crystal skull, a cipher for untold knowledge and psychic powers. But in true form, Indy squeezes out of this tight spot through fisticuffs and a high-wire chase. He makes his way through dozens of Soviet goons, onto a rocket sled, and stumbles into the eerily empty neighborhood of a nuclear testing site. Alarms begin to sound. A bomb will go off at any moment. Thinking fast, Indy shuts himself inside a lead-lined refrigerator, and the atomic explosion lands him miles away, miraculously unharmed.

This is a sequence embodying everything we love about the Indiana Jones films: the hero narrowly escaping certain death, dastardly un-American villains, chases from one type of vehicle to another, a fantastical and historically significant MacGuffin, and impossible jaw-dropping stunts. And yet, since its release in 2008, the term “nuking the fridge” has developed into an aphorism for failure, as the fourth entry in director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas’ adventure franchise was a perceived disaster. Almost twenty years passed both on and off-screen between The Last Crusade and this film’s release. In the interim, Ford’s mane went gray, Spielberg’s talent had time to explore and evolve, and the filmmaking team toiled away on a years-in-development project for a franchise that had ostensibly ended with a satisfying conclusion back in 1989. Moviegoer nostalgia for the series and expectations for the much-discussed sequel also ballooned beyond any possible hope of being satisfied. And despite eventual, generally positive critical reactions and impressive box-office numbers, the film was met with a lukewarm response and subsequently dismissed by fans. What a baffling turn for an incredibly entertaining picture.

Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was under scrutiny long before cameras started rolling, beginning in the mid-1990s with the first Hollywood reports that Spielberg and Lucas were talking to writers about a proposed sequel. Even though in the minds of the director and producer the film series had ended with The Last Crusade, the prospect of turning their back on the series altogether was not monetarily responsible from a Hollywood point-of-view. Lucas took the franchise to the small screen with The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles in the early 1990s. At the same time, Spielberg felt even on The Last Crusade that working again on an Indiana Jones film represented a step back in his maturation as a filmmaker. So for years, he resisted the idea of another film sequel. Nevertheless, Lucas wanted another film to follow their ongoing homage to Saturday matinee serials, but one set in the frequent serial genre of science fiction. Over the next decade, Lucas and Spielberg read scripts by various writers, like Jeb Stuart’s Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars and Frank Darabont’s Indiana Jones and the City of Gods, all featuring familiar elements: extraterrestrial artifacts, the progeny of Indiana Jones, and the marriage of our hero. Finally, a script by Jurassic Park screenwriter David Koepp was accepted by Spielberg, Lucas, and Ford. In the past, one of the three’s concerns about this or that screenplay inhibited the production from moving forward.

As the filmmakers dove into pre-production, they were forced to adopt a high degree of secrecy about their closed-set project to safeguard the film’s secrets. False sub-titles registered with the MPAA were meant to confuse media insiders, ranging from The Destroyer of Worlds to The Lost City of Gold to The Quest for the Covenant. In 2007, when the under-title Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was declared, internet news outlets began analyzing every aspect of the production and its history. Spielberg announced his intention to shoot in a style closer to the original films and would resist today’s computer-generated imagery where possible. His longtime cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, who collaborated with Spielberg since 1993’s Schindler’s List, looked to the original films to follow Douglas Slocombe’s style. The production shot mostly in the U.S. so that Spielberg could be close to his family; whereas previous entries featured exotic locales, this film shot many of its most complex scenes on the studio backlot. Meanwhile, every comment by the actors and crew involved was dissected and picked apart by the media and fans, promotional Lego toy sets were scrutinized by fans to determine elements from the hush-hush plot, and one thief broke into Spielberg’s office and stole a computer to retrieve details about the film.

As the filmmakers dove into pre-production, they were forced to adopt a high degree of secrecy about their closed-set project to safeguard the film’s secrets. False sub-titles registered with the MPAA were meant to confuse media insiders, ranging from The Destroyer of Worlds to The Lost City of Gold to The Quest for the Covenant. In 2007, when the under-title Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was declared, internet news outlets began analyzing every aspect of the production and its history. Spielberg announced his intention to shoot in a style closer to the original films and would resist today’s computer-generated imagery where possible. His longtime cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, who collaborated with Spielberg since 1993’s Schindler’s List, looked to the original films to follow Douglas Slocombe’s style. The production shot mostly in the U.S. so that Spielberg could be close to his family; whereas previous entries featured exotic locales, this film shot many of its most complex scenes on the studio backlot. Meanwhile, every comment by the actors and crew involved was dissected and picked apart by the media and fans, promotional Lego toy sets were scrutinized by fans to determine elements from the hush-hush plot, and one thief broke into Spielberg’s office and stole a computer to retrieve details about the film.

As they often do, expectations ran rampant and out of control both about the production’s secrecy and because of it. By the time Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull arrived in theaters, anticipations were already curbed by the degree of skepticism toward the project. Some critics, like Leonard Maltin, called it the franchise’s best entry since Raiders of the Lost Ark; others said it was the worst. Still, after the initial wave of favorable reviews, the picture earned $317 million in domestic receipts alone and became the third-highest earner of 2008, after The Dark Knight and Iron Man. Numbers aside, fan disapproval spread. Everyone seemed to turn on the film. Moviegoers voiced their disappointment in being only mildly entertained. The creators of South Park made an episode claiming Spielberg and Lucas “raped” the franchise. Costar Shia LaBeouf apologized to fans, saying he “dropped the ball” by agreeing to make the film, which he did without accepting the script. Ford later called LaBeouf an “ass” for making such a comment. Spielberg and Lucas defended the film. Suddenly this sure-thing sequel became a topic of much debate and dissent.

Among the most common arguments against Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is the feeling that Spielberg went too far in modernizing his technical approach to make this sequel. People seemed to expect that Spielberg and company would jump in a time machine back to the 1980s, make the film there, and return home with a result that would align with our fond memories of the franchise. But Steven Spielberg is not a time traveler, and 19 years passed between The Last Crusade and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Of course, Harrison Ford would look older, new technologies would be used, and the production overall would appear slicker than what came before. This is part of making movies; as time goes by, new technical elements are introduced to make filmmaking easier and cheaper and safer. The produced used 450 CGI shots to remove safety wires and render Amazonian jungle backdrops. After all, Spielberg’s cast and crew may have been able to survive dysentery from the exotic locales used twenty years ago when they filmed Raiders of the Lost Ark, but they’ve all since aged. It is crucial we understand this, just as we must accept that Harrison Ford is no longer a young man. But for an actor in his sixties, he still has all the magnetism, virility, and humanized flaws we expect from both the actor and character. What is it they say in Raiders of the Lost Ark? “It’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage.”

The other principal argument against Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is the science-fiction plotline and its inclusion of extraterrestrials, given that no outward sci-fi elements appear in the first three films. But first, consider the period in which Spielberg and Lucas have set their film. The 1950s marked the Atomic Age, where Cold War and nuclear paranoia reigned supreme: politicians conducted Red Scare-fuelled witch hunts, families built and stocked bomb shelters, schools practiced daily drills in case the bombs began to fall, and moviehouses were packed with tales of giant insects and lizards spawned from irresponsible nuclear testing. Science fiction was slowly becoming a reality, and ‘50s cinema the world over responded with B-movie entertainments that tapped into our worst fears, everything from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to Them! (1954) and Japan’s Godzilla (1954). In the same way that Temple of Doom evoked the horror genre to expand on the adventure-lined schematic of the Indiana Jones blueprint, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull employed components of Atomic Age escapism into a distinctive Indiana Jones setup. If the film was to take place in the 1950s—and logically, it must if it’s to explain the passage of time since the originals—then an Atomic Age plot was not only appropriate but requisite. Now consider the historical “ancient aliens” theories, which are more popular than ever some forty years after Erich von Däniken’s seminal study, Chariots of the Gods, which has become a passionate hypothesis for many archeologists. From this perspective, the film creates an adventure scenario around an existing archeological theory and runs with it, as opposed to combining the “Indiana Jones adventure genre” with another unrelated genre altogether.

The other principal argument against Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is the science-fiction plotline and its inclusion of extraterrestrials, given that no outward sci-fi elements appear in the first three films. But first, consider the period in which Spielberg and Lucas have set their film. The 1950s marked the Atomic Age, where Cold War and nuclear paranoia reigned supreme: politicians conducted Red Scare-fuelled witch hunts, families built and stocked bomb shelters, schools practiced daily drills in case the bombs began to fall, and moviehouses were packed with tales of giant insects and lizards spawned from irresponsible nuclear testing. Science fiction was slowly becoming a reality, and ‘50s cinema the world over responded with B-movie entertainments that tapped into our worst fears, everything from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to Them! (1954) and Japan’s Godzilla (1954). In the same way that Temple of Doom evoked the horror genre to expand on the adventure-lined schematic of the Indiana Jones blueprint, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull employed components of Atomic Age escapism into a distinctive Indiana Jones setup. If the film was to take place in the 1950s—and logically, it must if it’s to explain the passage of time since the originals—then an Atomic Age plot was not only appropriate but requisite. Now consider the historical “ancient aliens” theories, which are more popular than ever some forty years after Erich von Däniken’s seminal study, Chariots of the Gods, which has become a passionate hypothesis for many archeologists. From this perspective, the film creates an adventure scenario around an existing archeological theory and runs with it, as opposed to combining the “Indiana Jones adventure genre” with another unrelated genre altogether.

With this, audiences failed to identify with the film because the sci-fi elements remain as baffling as those 1984 audiences who could not connect with Temple of Doom because it was too scary. If this is the case, they are simply not “getting” the picture. But I will never understand the hatred for this film. As I wrote in my original review, “Much of your enjoyment of this latest entry resides in your ability to accept that the Indiana Jones series has always been about escapism, never realism.” And so, when detractors begin to complain that Indiana Jones would never survive a nuclear blast from inside a lead-lined fridge, one must laugh at the absurdity of the remark, because if this is the first time you’re questioning the reality of an Indiana Jones film, your concept of reality is out there. Those who went along with the series as Indy explored the catacombs of Venice (it’s a floating city!), ate chilled monkey brains with Indian royalty, and watched as Nazis instantly melted in the presence of holy spirits should have no trouble believing the wilder sci-fi eccentricities in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Those who cannot accept these traits, all tropes of not only sci-fi but the basis of adventure stories, have no reason to enjoy the earlier films.

What I appreciate most about the film is the way it enhances our view of Indy, and in doing so, connects to The Last Crusade through the inclusion of Mutt Williams (LaBeouf), who we eventually learn is Indiana Jones’ son, conceived with his old flame Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). Mutt, a ‘50s-style greaser straight out of American Graffiti or Rebel without a Cause, is to Indy as Indy was to his father, Henry Jones Sr. (Sean Connery, appearing only in photo form). During a motorcycle escape from pursuing Russian spies on a college campus, Mutt drives as Indy hangs on, feeling old and disapproving of this impetuous hothead. Mirroring that classic scene from The Last Crusade where Indy flips a Nazi cycle, and his father frowns, Indy’s role has been deepened by his age but not entirely reversed. In contrast to his father and now his son, we see our hero as both a bookish scholar and adventurer, the best of both worlds. Although Mutt has left school, he remains bright and a quick study, and under Indy’s tutelage, we can imagine that he too will become like his father, an academic treasure-seeker. For all the character’s comic throwback traits, Mutt reminds us that Indiana Jones is forever a man rebelling against the distant, purely studious example set by his father.

To be reasonable, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is not a perfect film. What film is? There’s always a detail or two that, if changed, would make the best films even better. But these are commonly superficial concerns. Perfection is a state of mind. What remains unfortunate about the production are minor details and passable moments quickly forgotten. The climax relies too much on CGI when an interdimensional alien seems to look into the camera, his craft spinning around in a flux of colors and imagery far removed from anything this franchise has seen before. When LaBeouf’s Mutt Williams swings from vines, no doubt the filmmakers’ nod to Tarzan serials, he’s accompanied in this iffy effect by CGI monkeys—it’s a silly moment, but in a fun way that those familiar with the Saturday serials should appreciate. Peruvian jungle scenes feature CG-thickened forests that resemble a cheaper production’s green screen work. But then there’s the “nuke the fridge” scene, which is so wonderfully over-the-top that I can’t help but love it. After all, moments like these would be right at home in the B-movie genres the filmmakers sought to emulate, and Indiana Jones has never been based in realism. In reality, Indiana Jones should be dead a hundred times over, having survived booby-traps galore, escaped impossible multi-vehicle chases, and transcended history (and fact) to preposterous degrees. But Indiana Jones isn’t reality.

To be reasonable, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is not a perfect film. What film is? There’s always a detail or two that, if changed, would make the best films even better. But these are commonly superficial concerns. Perfection is a state of mind. What remains unfortunate about the production are minor details and passable moments quickly forgotten. The climax relies too much on CGI when an interdimensional alien seems to look into the camera, his craft spinning around in a flux of colors and imagery far removed from anything this franchise has seen before. When LaBeouf’s Mutt Williams swings from vines, no doubt the filmmakers’ nod to Tarzan serials, he’s accompanied in this iffy effect by CGI monkeys—it’s a silly moment, but in a fun way that those familiar with the Saturday serials should appreciate. Peruvian jungle scenes feature CG-thickened forests that resemble a cheaper production’s green screen work. But then there’s the “nuke the fridge” scene, which is so wonderfully over-the-top that I can’t help but love it. After all, moments like these would be right at home in the B-movie genres the filmmakers sought to emulate, and Indiana Jones has never been based in realism. In reality, Indiana Jones should be dead a hundred times over, having survived booby-traps galore, escaped impossible multi-vehicle chases, and transcended history (and fact) to preposterous degrees. But Indiana Jones isn’t reality.

What I love about the film are its simpler details. Take the bright comic-book characters straight out of an adventure magazine: the double-crossing “triple agent” Mac played by Ray Winstone, complete with devilish Errol Flynn mustache; Blanchett’s flawless portrayal as a rigid, domineering villainess whose hands emasculate even Indy when placed on his knee during his interrogation; Allen’s delightful reprisal as Marion, her head cocked with a grin and fists charmingly at her hips; John Hurt’s off-his-rocker archeologist. And then, there are the action sequences. The most thrilling of them occurs mid-film, where Marion crashes a vehicle into a hill of flesh-eating ants. Everyone runs as these critters chitter along, swarming over poor Russian saps with bad enough luck to trip and fall. As Indy engages a goon in fisticuffs, Spalko climbs off the ground away from the ants, but the hungry things stack onto one another to almost reach her. All the while, we’re squirming and shouting eeek for the villain of all people! But Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is never better than that first scene, when the Russians pull Indy out of a trunk and push him to the ground. Spielberg shoots his silhouette against a car. We see that iconic image appear as Indy collects himself and secures his fedora. Yes, this is great filmmaking.

So many moments in this film make me want to holler out, “You still got it!” to everyone involved, especially Harrison Ford, who, 19 years later, still encapsulates what it means to be an adventure hero. Conversely, only two or three significant moments feel out of place in the entire film, and they’re fleeting incongruities of dodgy CGI, all amounting to about a minute of screentime in an over-two-hour spectacle of blissful Atomic Age nostalgia, humor, and adventure. From Elvis on the soundtrack to Spielberg’s wonderful staging of action sequences, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull holds a deserving place amid its predecessors in the franchise, which, categorically speaking, could be ordered from best to worst in the order they were made. Then again, there is no “worst” here, not really. Each picture is great, while this fourth entry is simply the least great. This does not make it a bad film. Its greatness is lessened only when compared to three films that epitomize the adventure genre, and moreover, stacked against the inconsolable expectations of fans wanting a film shot in 1981 instead of 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review