Reader's Choice

India Song

By Brian Eggert |

The title of Marguerite Duras’ film India Song refers to its recurring music by the same name, written by the Paris-based, Argentinian-born Carlos d’Alessio. Its melody is chic and modern for the period, not at all an Indian song but a French riff on American slow jazz, creating a curious juxtaposition against the film’s setting: the French Embassy in Calcutta sometime in the 1930s. The song plays repeatedly, filling the oppressive stillness of the film’s characters with meaning, while lending their few slow movements the same methodical musical rhythm. Even the smallest of gestures such as a walk across a room or a kiss contain the weight of this temporally enforced rhythm, which, onscreen anyway, leads nowhere. The result gives a tantric quality to every scene, each of which prolongs itself for an orgasm that never comes. By this very nature, the film can’t help but feel somewhat disappointing and anticlimactic. “Death is the end, the annihilation,” said Duras about her film, not referring to la petite mort but a literal death. Still, Duras’ approach is every bit as ambiguous and rigorously conceived as her scripts for Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and especially Last Year in Marienbad (1961), both directed by Alain Resnais.

It’s oddly foretelling that Duras’ novel of the same name from 1973 was originally published with the subtitle “Texte Théâtre Film,” given the material’s appearance as a book first, followed by an abandoned commission for the British National Theater, and then the 1975 film. Still, watching India Song forces one to wonder how it could work outside of cinema. In the film, the great Delphine Seyrig plays Anne-Marie Stretter, the wife of Calcutta’s French Ambassador. Along with her string of lovers and a rejected Vice-Consul of Lahore (Michael Lonsdale), who yearns to sleep with her, she wastes away out of boredom and existential dread in a dilapidated embassy. When she’s not impliedly sleeping with other men, she’s experiencing a profound sense of dissatisfaction with imperialist life. However, the film is far from a straightforward narrative, as it omits synced sound. When there are voices, they come from off-screen; the actors’ lips never move, and the voices themselves have an uncertain origin. It’s a strategy that creates an innate conflict between that which appears and does not appear, and a question about whether these voices belong as part of the diegesis, albeit in some realm not visible to human eyes, or if they exist as non-diegetic observers operating from outside of the narrative.

Duras and her crew structure the film in layers, syncing sound and image with all the regimentation of an elaborate equation whose solution cannot be reached within the limited space of this review. Similar to Last Year in Marienbad, the characters in India Song stand around on an ornate property, often unmoving, or moving with such a slowness that their inaction invites consideration. Their immobility has two functions: to “slow down the blood” and counteract the heat of India, and to encapsulate the sense of prolonged occupation that comes with the film’s postcolonial critique. The characters themselves appear in mirrors, a reflection of a person rather than the whole; in the same way, the film’s narrative is reflected through time as voices convey what has been and what will be. The voices come from various sources: At first, we hear omniscient female voices from outside of time; one asks questions about Anne-Marie, and the other answers with exposition about her past and eventual suicide. Later, we hear the inner voices of the characters onscreen. Later still, we hear dialogue exchanged, even though the characters cannot be seen speaking. It’s a dialectic between sound, represented by disembodied voices on the soundtrack, and vision, relating to what appears onscreen.

Critic Carol Murphy, writing about Duras’ book, described the story as “about the destructiveness of love,” dramatizing “the futility of love” through its circular passages and narrative. To that end, Duras uses the French Embassy as a symbol for something that once was great but has since crumbled—imagery that acknowledges both the failure of colonialism and, arguably to a greater extent, love. The embassy contains rooms decorated with putrid green and filled with dust, old furniture, and wilted flowers with the smell of “leprosy” about them. Indeed, “leprosy” remains a central motif of India Song, as the exclusively French characters wander about, awake at all hours of the night, suffering from “leprosy of the heart.” When, later in the film, an embassy reception takes place in a large salon, most of it appears through the reflection of a massive mirror. No part of India Song contains forward action or dramatic movement; it’s a film about a state of literal and figurative reflection.

India Song, as mentioned above, follows a musical rhythm in its structure and form. Shooting at the Palais Rothschild in Boulogne, director of photography Bruno Nuytten captures the exteriors in a series of repetitive images. Breaking the “leprosy” of the interior spaces, the film ventures outside again and again for shots of nature, the embassy’s exterior, and the grounds, all in shots that pan left to right—the direction of progress in Western reading. Likewise, Duras and Nuytten repeat the same interior spaces, the same drawing-room, the same mirror, each framed similarly. These formal rhythms, captured with strategic timing by Duras and editor Solange Leprince, reflect the musical structure and melancholy tune “India Song,” with its winding, circular reprise. Once the viewer becomes attuned to these repetitions, the characters, in all their ennui, become ever more relatable—if only because we feel their overwhelming sense of monotony. Even as the visual patterns remain rhythmic, the overlapping voices diverge, testing the viewer to keep them straight as they speak about different subjects at the same time. Before long, Duras’ voice enters the mix, and she begins speaking of her own experiences that have nothing to do with the onscreen story. It’s at this moment that the film becomes a challenge to follow as a narrative but clearer as a work of personal art.

Even as the meaning of India Song overall sometimes proves deceiving, if only because the message seems overly clear and therefore unnecessarily complex in its presentation, there are more straightforward aspects to appreciate—namely, the performances. Duras shot each scene against tapes of recorded voices that expressed what was happening in the scene and how the characters were feeling, thus describing the meaning of the scene as it was performed. This led to a phenomenon that Duras describes in Seyrig’s performance as “listening with her whole body.” Seyrig appeared in India Song in the same year she gave her greatest performance (in Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles), and her presence is rooted in movement and evocative silences. Though the film consists of vacant parties with static figures in empty rooms, where some characters are heard but not seen, the visible actors speak in body language. Even as their conversations unfold in voiceover, each actor expresses themselves with an equal measure of withdrawal, yet each is present in their minimalized gestures. As the almost wraith-like voices convey inner thoughts and feelings, the actors inhabit each scene through a purely physical performance. It’s a tactic that might be more admirable if Duras’ script had avoided being self-referential about her approach: Note how one voice remarks about a character’s “way of being silent” in an almost winking observation, or when the Vice-Consul asks Anne-Marie (from a voice off-screen), “Do you hear my voice?”

Duras was inspired to tell this story from her experiences as a child in French-occupied Indochina, and India Song, much like Claire Denis’ postcolonial masterpiece White Material (2009), uses its form as a metaphor for her critique of imperialism. Using a style reminiscent of Michelangelo Antonioni, albeit lacking the same urgent beauty, Duras establishes a vast expanse between the local population and the imperialist Europeans. After all, the only Indian seen or heard is a “mad beggar” woman who screams from outside of the embassy. The substance of her cries is left unknown; Duras doesn’t offer a translation, at least not in the film’s subtitles. She extends that metaphor into the film’s theme about “the destructiveness of love,” as the Vice-Consul, inconsolable as Anne-Marie will sleep with almost anyone else except him, screams with madness into the night (again, no subtitles provided). “The longer you stay in Calcutta,” one of the voices says, “the more you forget everything else.” Colonialism forces one to lose perspective, Duras seems to say, leaving one in a state of neither pleasure nor pain—it’s “nothing” to live in India.

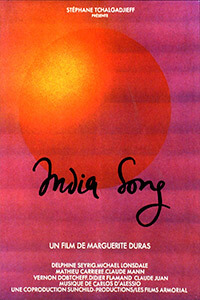

It’s no surprise that the setting sun, spied in India Song’s first shot and on its theatrical poster, is the film’s enduring symbol. Like a French postcolonial version of Satyajit Ray’s The Music Room (1958), the film captures the decline of an era (the remaining sectors of French India had been liberated about two decades before the film’s release). But even as one views India Song with an appreciation of its symbolism and bold formal experimentation, one must question whether it produces any feeling. Vincent Canby called the film an “overly intellectualized mistake”—a harsh assessment that nonetheless captures how Duras has thought out every detail, resulting in an austere aesthetic and unwavering formal precision that have a distancing effect. Unlike Resnais in Last Year in Marienbad or Antonioni in L’Avventura (1960), India Song lacks the same joy in its filmmaking—its emotions are bound up inside the visual and aural experiment, its ambiguity, and its symbolism. But it doesn’t evoke feelings of love or its destruction.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Rodarte-Quayle. Thank you for your support!)

Bibliography:

Duras, Marguerite, and Jan Dawson. “India, Song: A Chant of Love and Death.” Film Comment, vol. 11, no. 6, 1975, pp. 52–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43753025. Accessed 2 May 2020.

Loutfi, Martine A. “Duras’s India.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 3, 1986, pp. 151–153. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43796262. Accessed 2 May 2020.

McMahon, Laura. “Lovers in Touch: Inoperative Community in Nancy, Duras and ‘India Song.’” Paragraph, vol. 31, no. 2, 2008, pp. 189–205. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43151883. Accessed 2 May 2020.

Murphy, Carol J. “India Song by Marguerite Duras.” The French Review, vol. 49, no. 2, 1975, pp. 296–297. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/388729. Accessed 2 May 2020.

Ropars-Wuilleumier, Marie-Claire, and Kimberly Smith. “The Disembodied Voice: India Song.” Yale French Studies, no. 60, 1980, pp. 241–268. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2930015. Accessed 2 May 2020.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review