Independence Day

By Brian Eggert |

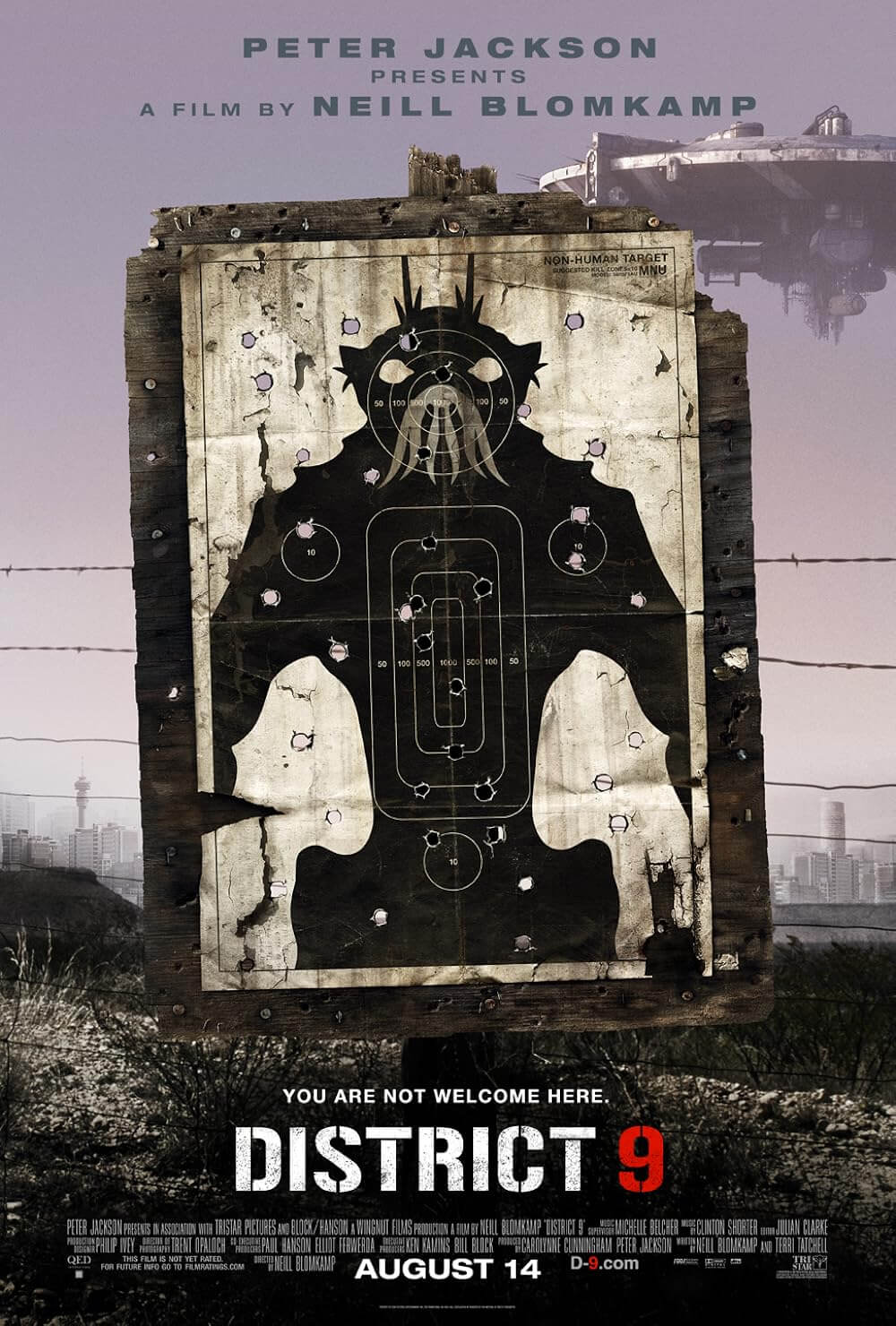

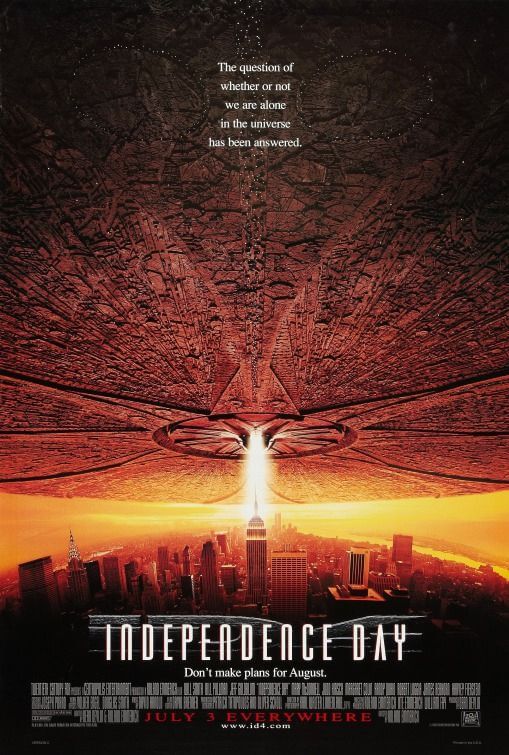

The nineties were a time when movie titles featured strange, often nonsensical numeric symbols. Sure, the nicknamed T2 abbreviated Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) with enough clarity. But no one really understood why 1992’s Alien³ was to the third power; it certainly wasn’t three times the film that Alien was. Replacing the “v” in Se7en (1995) with a “7” can’t help but force the reader’s head to the left in a hopeless attempt to make that “7” a “v” again. Among the most popular and successful of these was Independence Day, which debuted in 1996 with the lettering ID4 on the poster. This always confused me. “Independence” and “Day” are covered by the “I” and “D” respectively. The “4” is curious. There were not three previous movies leading up to ID4. Rather, the “4” suggests America’s Independence Day on July 4, 1776. Given the movie’s global alien invasion theme, the title is an eyebrow-raising demonstration of American exceptionalism that sees the world’s day of independence from alien invaders through a pointedly American lens.

After all, nearly 200 countries celebrate their separation or unification from a ruling state with an independence day of some form or another. By having Earth’s independence from aliens coincide with America’s independence from Great Britain, writer-director Roland Emmerich and his producer-writer Dean Devlin engage in a troublingly jingoist perspective—one that hopes to establish the United States as Earth’s defender. When President Whitmore (Bill Pullman) gives his rallying speech to a ragtag group of fighter pilots, he announces: “We can’t be consumed by our petty differences anymore. We will be united in our common interests.” In short order, his words of unity become hollow: “The Fourth of July will no longer be known as an American holiday… Today we [the world over] celebrate our Independence Day!” Indeed, the new Independence Day declared by Whitmore to an audience of Americans allows everyone else to be more like America through their victory. Had the speech been broadcast to the world over, perhaps it would have had a different subtext. But it wasn’t, so it doesn’t. Of the speech, Movie Review UK critic Neil Smith wrote,”[The speech is] the most jaw-droppingly pompous soliloquy ever delivered in a mainstream Hollywood movie”.

In this sense, and many others, Independence Day has aged badly since its release in the summer of 1996, when it earned $306 million in domestic receipts, despite mediocre reviews. The blockbuster also spurred an insurgence of Emmerich-directed disaster movies (Godzilla, The Day After Tomorrow, and 2012), many of them achingly stupid, and prompted a succession of science-fiction movies that gradually led to the mass popularization of the genre (Contact, Starship Troopers, Men in Black, The Fifth Element, and many others). Today the trend continues, with major sci-fi summer tentpoles like Avatar or Edge of Tomorrow appearing in theaters every month. The film itself has become overplayed and cliché. Scenes like Whitmore’s speech or when Will Smith famously declares “I’ve got to get me one of these!” are unintentionally laughable today, whereas the filmmaking style, heavily borrowed from Steven Spielberg’s body of work, was re-borrowed by Michael Bay for Armageddon.

By the film’s release in 1996, The X-Files (1993-2002, 2016) had been teasing secret alien invasions for years with an ongoing plot about genetic colonization. One of the most popular network series of the 1990s, The X-Files was a weekly dose of sci-fi conspiracies and monsters-of-the-week that prepared audiences for any number of fringe topics for further exploration in theaters. Before Emmerich and Devlin took a cue from The X-Files and conceived their alien invasion story, Emmerich had directed a number of B-level sci-fi films, many back in his home of West Germany, and a few hits for Hollywood (Universal Soldier, 1992; Stargate, 1994). In an oft-told anecdote, Emmerich and Devlin came up with the idea for Independence Day during a press conference for Stargate, when a member of the press prompted the idea of a full-on, massive-scale alien invasion. Though it seemed like an impromptu notion, Emmerich and Devlin’s script would resemble alien invasion staples—specifically, H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds and Byron Haskin’s 1953 movie version.

By the film’s release in 1996, The X-Files (1993-2002, 2016) had been teasing secret alien invasions for years with an ongoing plot about genetic colonization. One of the most popular network series of the 1990s, The X-Files was a weekly dose of sci-fi conspiracies and monsters-of-the-week that prepared audiences for any number of fringe topics for further exploration in theaters. Before Emmerich and Devlin took a cue from The X-Files and conceived their alien invasion story, Emmerich had directed a number of B-level sci-fi films, many back in his home of West Germany, and a few hits for Hollywood (Universal Soldier, 1992; Stargate, 1994). In an oft-told anecdote, Emmerich and Devlin came up with the idea for Independence Day during a press conference for Stargate, when a member of the press prompted the idea of a full-on, massive-scale alien invasion. Though it seemed like an impromptu notion, Emmerich and Devlin’s script would resemble alien invasion staples—specifically, H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds and Byron Haskin’s 1953 movie version.

After receiving a quick greenlight from 20th Century Fox for their script, Emmerich and Devlin were given a budget of $75 million to accomplish a then-record number of special FX shots and pyrotechnics. According to a commentary track on the DVD for Independence Day, the U.S. military originally agreed to provide army vehicles and costumes to the production, but they later refused when Emmerich would not remove references to Area 51. (NOTE: The Fox Mulder in me recognizes this is all but confirmation that Area 51 is a vast conspiracy. Why else would the military back out? There’s no other explanation for this behavior.) Effects artists built models of famous landmarks, all of them in the United States—we don’t see the Eiffel Tower or Taj Mahal—and made them explode real good, launching a movie trend in which famous landmarks are destroyed onscreen. Production designer Patrick Tatopoulos designed the rather dull aliens, whose big heads and telepathic abilities remained close to established concepts for aliens (once again, already popularized by The X-Files). The production would go on to earn an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, though much of the green screen work looks dated by today’s standards (most notably, the destruction of the White House and the digitally added helicopter in the foreground, or the dog who leaps to avoid a fireball).

Epic, yet also narrow in scope, the story follows a number of individuals who survive the initial global attack of an alien invasion. To distracting effect, the characters are exclusively American, despite several countries around the world being targeted by the 15-mile-wide flying saucers that have burned their way into our atmosphere and position themselves over major cities. Never mind how Africa, Germany, Japan, or hell, even England think about what’s going on—America is what matters, the filmmakers seem to say. The masses in U.S. cities flee and loot in response to the visitors, causing a few traffic accidents. But the reactions are surprisingly lacking in their absolute terror (a single scene depicting suicide or a religious zealot barking “The End is nigh!” would have added some realism). A few enthusiasts position themselves atop skyscrapers, holding signs that say “Beam me up!” and such. Only David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum, playing a dumbed-down version of Seth Brundle and Ian Malcolm), an MIT-educated cable guy, recognizes a countdown signal embedded in our satellites.

The thinly drawn characters are each two-dimensional at best: Will Smith’s Captain Steven Hiller adopts the actor’s bombastic Will Smith-ness from Bad Boys (1995), making way for that same persona in Men in Black, Enemy of the State (1998), and Wild Wild West (1999). His character’s only qualities seem to be his cockiness, and his plans to propose to his stripper girlfriend (Vivica A. Fox). David’s exaggeratedly Jewish father Julius (Judd Hirsch) appears as comic relief and a moral center. Randy Quaid’s former pilot turned drunk also provides comic relief, playing Russell Casse, a less disgusting version of National Lampoon’s Cousin Eddie—yet again leading his family in a Winnebago—and making dismissed claims that he was an alien abductee. More official types have even less personality or identifying traits, except that they’re played by a roster of familiar character actors: Robert Loggia, Margaret Colin, James Rebhorn, and Adam Baldwin. Among them, Brent Spiner (better known as Data from the Star Trek: The Next Generation series), plays an eccentric scientist who’s been squirreled away in Area 51 for too long.

Most of these characters utter phrases like “My God” or “Heaven help us” or “May God have mercy on our souls” at the size of the alien craft or dire situation. Independence Day is a Christian-exceptionalist movie as well. A scene cut from the theatrical version shows Julius asking soldiers and White House staff to join him in a Jewish prayer, which they do, but the scene was removed to maintain Independence Day’s target audience: God-fearing Americans. (NOTE: The scene was restored in the home video “Special Edition” cut.) Meanwhile, the plot borrows from War of the Worlds, as mentioned above. When David concocts a plan to upload a “virus” into the mother ship, it’s not unlike an updated version of Wells’ classic, where the aliens are wiped out by the common cold. At any rate, David’s plan works, the shields protecting the alien craft shut down, and the Americans obliterate the aliens. Though potentially billions have died the world over, all seems to end well.

From start to finish, the story’s logic is creaky, even by blockbuster standards. Just ignore that aliens with the ability of intergalactic travel and the capacity to engineer 15-mile long spacecraft don’t have a way to communicate without our puny human satellites, despite their mother ship shadowing the Moon. Pay no attention to how, after detonating a missile at the attack ship’s center in the finale, the other jets somehow fly 7.5 miles in a matter of seconds to escape the falling ship. Don’t bother questioning why, after the arrival of the alien ships, everyone still refuses to believe Russell’s abduction stories. Shouldn’t they have pity on him, given that his abduction undoubtedly led to his alcoholism? Somewhere, Fox Mulder’s head explodes at the ridiculous amount of evidence to support Russell’s claims, and the persistent doubts against him. The effect is not unlike someone who sees Independence Day as a piece of brainless Hollywood drivel, and yet faces its overwhelming popularity among audiences. A critic is bound to feel like Russell, the village drunk who professes “The aliens are coming!” only to be humiliated by slack-jawed yokels on local television.

Indeed, Independence Day isn’t a smart movie, nor even a blockbuster of average intelligence. It’s a stupid movie that drains every ounce out of novelty out of its subject matter and squanders it on explosions and CGI. And yet, people love it. Emmerich’s movie worked well enough in its day in terms of moronic escapism, but audiences have, debatably, grown less tolerant of dim-witted sci-fi since 1996. Perhaps it’s more significant for further synthesizing America’s then-current passion for science-fiction, alien invasion scenarios, and government conspiracies thanks to The X-Files—although, this quality is so absolutely overshadowed by the movie’s blockbuster-ness that it’s almost not worth mentioning. (Also, The X-Files had a perfectly entertaining movie itself in 1998, no doubt as a result of Independence Day‘s popularity.) Today, the term “mind-numbing” has never been more appropriate, since sitting through Emmerich’s proceedings, gaps in logic and all, wears down on the viewer until their brain all but shuts down, except for rudimentary functions that remain drawn to the explosions and FX onscreen. For those purposes—and those purposes alone—Independence Day could be called entertaining.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review