In the Heart of the Sea

By Brian Eggert |

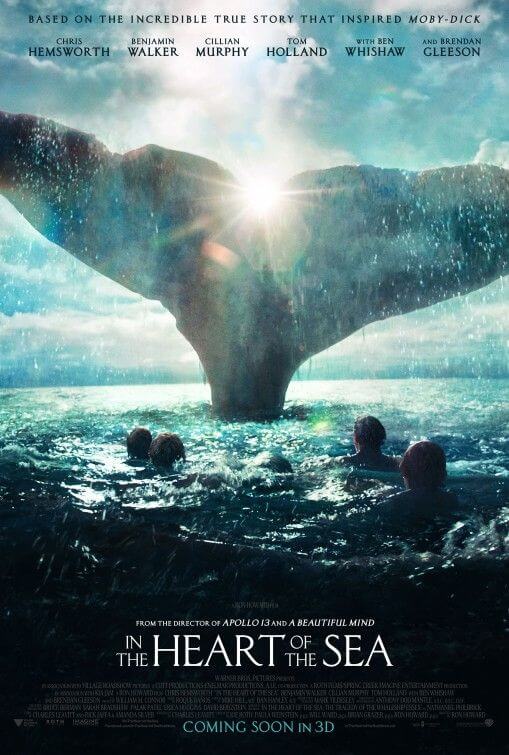

Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2000. Its harrowing true story follows the Essex, a doomed ship in the bygone era of 19th-century whaling. A fascinating page of history, the Essex hailed from Nantucket and was eventually demolished by a gargantuan, white sperm whale in 1820. The crewmembers, lost at sea for months, endured the punishing elements and engaged in cannibalism to survive. Herman Melville used this story, among others, to conceive his Great American Novel, Moby Dick, which dramatized the tale into a meaningful and powerful narrative. Rather than adapt another Hollywood-style Moby Dick, director Ron Howard resolved to take on In the Heart of the Sea itself. But the true story hasn’t been shaped for the dramatic purposes of cinema, and the effect is largely a drab and plodding experience onscreen, with the occasional strong performance to keep us involved.

Charles Leavitt (Blood Diamond) adapted Philbrick’s novel into a classical sort of structure where, in 1850, the young Melville (Ben Whishaw) tries to convince the Essex’s last surviving crewmate, Tom Nickerson (Brendan Gleeson), to tell his story. After accepting a wad of cash to recount the worst chapter of his life, Nickerson, determined to find absolution by talking about these events for the first time, begins his tale. The film fades into a flashback starting in 1820, when Nantucket was the world’s premier whaling town. Whalers embarked from and returned to port sometimes more than a year later with thousands of gallons of whale oil in their cargo, which was soon burned to keep the world illuminated at night. Nickerson, then just a boy (played by Tom Holland), watches as tensions build between the Essex’s new, untried, over-privileged captain George Pollard Jr. (Benjamin Walker) and his more experienced first mate, Owen Chase (Chris Hemsworth)—an obvious conflict of class, ego, and skill between them, all of which come to a head on the high seas.

Arguments persist between Pollard and Chase, with the second mate (Cillian Murphy) loyal to Chase, but it becomes clear that Pollard doesn’t have the respect of his crew and needs a man of action like Chase to keep everyone alive. As Nickerson somehow recounts conversations that took place behind closed doors or elsewhere he could not witnessed, the story unfolds that the Essex made its way around Cape Horn after discovering the Atlantic had few whales in sight. Now in the Pacific, the crew finds a veritable treasure trove of whales and begins hunting. All at once, the fabled white whale of those seas attacks the crew; the buck capsizes their ship and leaves the crew stranded over three lifeboats. And if suffering from the ensuing dehydration and starvation isn’t enough, the white whale pursues them, seemingly out of vengeance. (After all, the whalers were throwing harpoons at other whales. I would be angry too if someone threw harpoons at my family.) The story drags in the final third with dull, familiar scenes of skeletal men wasting away, sunburnt and finally drawing lots to determine who dies to feed the others.

Much of the $100 million production looks surprisingly cheap for a film by veteran Howard. Scenes on the sea show obvious signs on greenscreen work, with an embarrassing distinction between the real-life foregrounds and artificial backgrounds. Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle shoots some scenes quite typically for a historical epic, in a pointedly nautical color scheme, although the humans seem like the only real thing onscreen. All shots of the ocean, Nantucket, and underwater sequences appear in none-too-impressive computer animation. Elsewhere, editors Daniel P. Hanley and Mike Hill incorporate curious, ultra-close-up shots that look to be shot with a GoMotion camera housing a fisheye lens. No doubt these shots are meant to give the film a really there vibe, but the CGI and intermittent scenes between Melville and the older Nickerson ruin any hope of documentarian-worthy verisimilitude.

In the Heart of the Sea isn’t the story Melville told. It involves moments of tragedy and grim human desperation when faced with death. Melville sought to explore his Captain Ahab’s attempt to conquer Nature, and thus God, through his obsession, madness, and unbridled anger at the world. The film shows the depths of human physical suffering, not unlike 2014’s Unbroken, but also shows the lengths people will go to ensure the world gets the fuel it needs (a theme overemphasized in a final scene). It does not, however, consider any existential suffering. Less of a commentary is the obvious savagery against animals. Whaling may be deemed illegal by most countries today, but there’s still a few hangers-on who cling to the cruel industry. The filmmakers lost an opportunity to sympathize with these beautiful, intelligent mammals, and instead resort to depicting the “demon whale” as just that—regardless of a CGI moment or two where the whales feel more like victims than a resource. As a result, it makes sympathy for the Essex crew hard to come by.

Howard seems at odds with the material, split between whether he wants to make a historically accurate story about an ill-fated seafaring crew, or whether he wants In the Heart of the Sea to feel like a classical Hollywood sea epic. Lewis Milestone’s 1962 take on Mutiny on the Bounty came to mind—indeed, there are even counterparts for a stubborn Captain Bligh and upstart Fletcher Christian here. Likewise, the acting styles performed by Hemsworth and Walker feel more theatrical than authentic, their natural accents apparent under a forced Nantucket brogue. The material presents a serviceable survival yarn but carries none of Melville’s singular weight or even the historical insight served by Philbrick’s novel. Feeling like a movie from start to finish in all the worst ways, In the Heart of the Sea is perhaps most notable for the books it might inspire its audience to read.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review