Reader's Choice

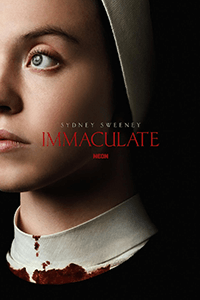

Immaculate

By Brian Eggert |

Watching Immaculate is a frustrating, disappointing experience because its premise and themes have incredible potential, almost enough to overlook its flaws. But that’s difficult when the movie fails to imbue its derivative setup and horror clichés with new life or tell a story that doesn’t feel woefully underwritten. Director Michael Mohan reteams with Sydney Sweeney, the star of his 2021 feature The Voyeurs, for a nunsploitation flick barbed with a sharp religious critique and drenched in blood. It warrants interest due to its timely themes concerning women’s ever-eroding right to choose what happens to their bodies. If only the writing, performances, and execution were as inspired as its worthwhile ideas, Immaculate may have better served them. However, a movie is more than just an ideology that the viewer agrees with or doesn’t agree with. But Immaculate takes itself too seriously to have fun with its genre and sensationalized concept, while the B-movie scenario proves too absurd to justify its grave tone.

The narrative involves Sister Cecilia (Sweeney), a young American novitiate from Michigan who travels to Italy to serve at Our Lady of Sorrows. The isolated hospice convent for dying nuns resides over ancient catacombs and houses one of the nails used to crucify Jesus. But there’s something wicked inside. A prologue involving another young nun (Simona Tabasco), who tries to escape, only to be attacked by a group of dronelike sister sentries, implants some dread about what will befall Cecilia. When she arrives, the demure protagonist, who apologizes when someone interrupts her using the restroom, struggles to adapt to her hardened, cloistered surroundings. And several oddities ignite her suspicion that something’s very wrong: At night, she dreams of nuns in red masks examining and stabbing her. Are they dreams or memories? One nun has crucifixes branded on the bottom of her feet, and another nun cuts a lock of Cecilia’s hair, announcing, “All of us adore you!” However, the strange behaviors are explained away as the wavering minds of the elderly and sickly.

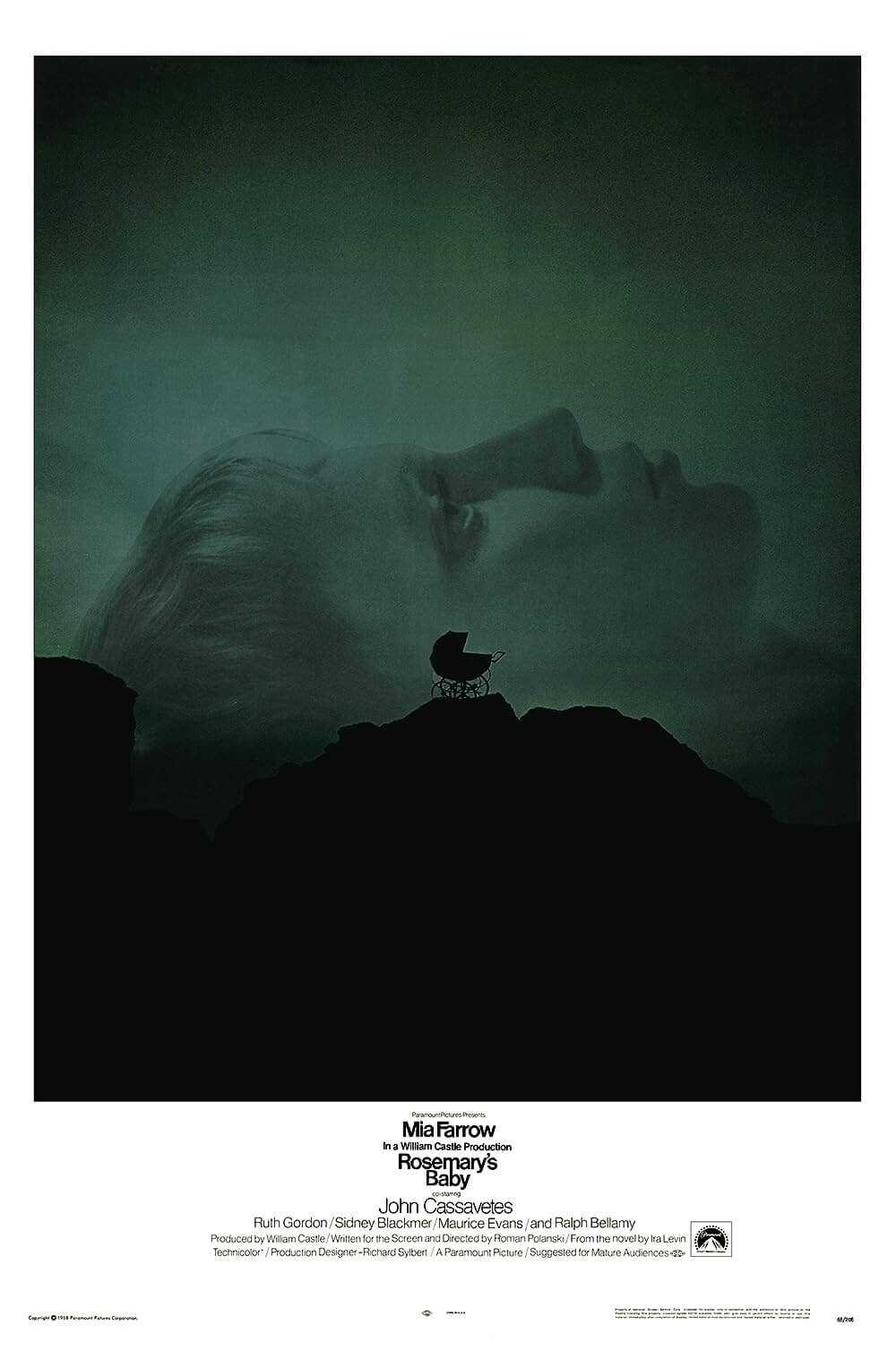

When Cecilia suddenly becomes pregnant, despite being a virgin, the convent’s leadership—Father Sal Tedeschi (Álvaro Morte), the resident Cardinal (Giorgio Colangeli), and the Mother Superior (Dora Romano)—embrace her as a Mother Mary figure. Almost everyone in the convent worships her as the host of the Second Coming; Cecilia even goes along with being dressed up and praised like an icon. But their zealotry is extreme, complete with a familiar “It’s all for you!” self-sacrifice. Indeed, Andrew Lobel’s script draws liberally from Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Omen (1976), attempting to instill a frantic paranoia in Cecilia as she questions what she’s carrying and the motives of those around her. When she investigates, she does so by searching in the dark with a flickering candle or an unreliable flashlight, leading to inevitable and ineffective jump scares. Cecilia soon finds herself at the mercy of the torturous convent, which insists on controlling her access to healthcare and limiting her contact with the outside world, despite her teeth falling out and nails peeling off from whatever’s growing inside her womb. The situation soon reveals itself, and Cecilia realizes she’s at the center of a warped Catholic conspiracy to resurrect their savior using genetic engineering.

The 89-minute runtime doesn’t allow for much characterization or dimension beyond Cecilia’s evolution from a mousy nun to a raging defender of her body. The story criticizes those who justify their warped actions by evoking God’s will and saying, “If this is not God’s will, why does God not stop us?” The message isn’t subtle. If only the movie’s style were equally as bold. Other critics have compared this setup to an Italian Giallo picture, with Mohan evoking the similarly themed What Have You Done to Solange? (1972). But Mohan’s aesthetic feels subdued by comparison, whereas Giallo paints in bold colors and bombastic visual flourishes. Mohan and cinematographer Elisha Christian shoot in admirably natural light and achieve a muted color palette, apart from the displays of red in the bloody finale. At the very least, a memorable score by Will Bates gives the movie a spooky atmosphere.

Cleverly, the movie doesn’t initially reveal the era in which it occurs. The viewer might assume the setting is the mid-twentieth century based on the surroundings. When Mohan introduces a cell phone and a modern vehicle, he delivers a subtle twist to emphasize the movie’s relevance to the contemporary viewer. This isn’t some story that happened long ago; it’s happening right now. To be sure, there’s an unmistakable commentary on how the mostly conservative Christian members of the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade in 2022, which has given rise to many states limiting or outlawing access to abortion. Great horror films often tap into contemporary anxieties and political issues, and Immaculate comments on how patriarchal religion uses its dogma to control women’s bodies. That the distributor at Neon put the film in theaters a week before Easter, when theaters are packed with Christian-themed cinema to exploit the occasion, is firebrand marketing at its best. If only the movie were better.

Immaculate might be fun as camp, in the true sense of the word, meaning it’s so bad that the viewer enjoys the experience but not as the filmmakers intended. Indeed, moviegoers in my screening turned on the picture after a while, openly chuckling at the script’s ham-fisted dialogue, Sweeney’s flat line delivery, and other moments that failed to land. Sweeney, the current obsession of celebrity entertainment outlets, is outmatched by material that reveals her limited range and screen presence. She doesn’t inhabit the role; we can always see the effort in her acting. The final scene, where the camera remains on Cecilia’s bloodied face as she takes action, should be a stunner. Mohan’s choice should make us think about how a woman’s identity means more than what she can produce, about how she should have the right to choose, but under politics informed by religious ideology, she must fight and claw for that right. Instead of confronting the viewer with these ideas, Mohan and Sweeney deliver one underwhelming scene after another. The viewer can always see how a different filmmaker, a better script, and a stronger lead may have made this material feel more alive and less like a missed opportunity.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on March 26, 2024.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review