I’m Thinking of Ending Things

By Brian Eggert |

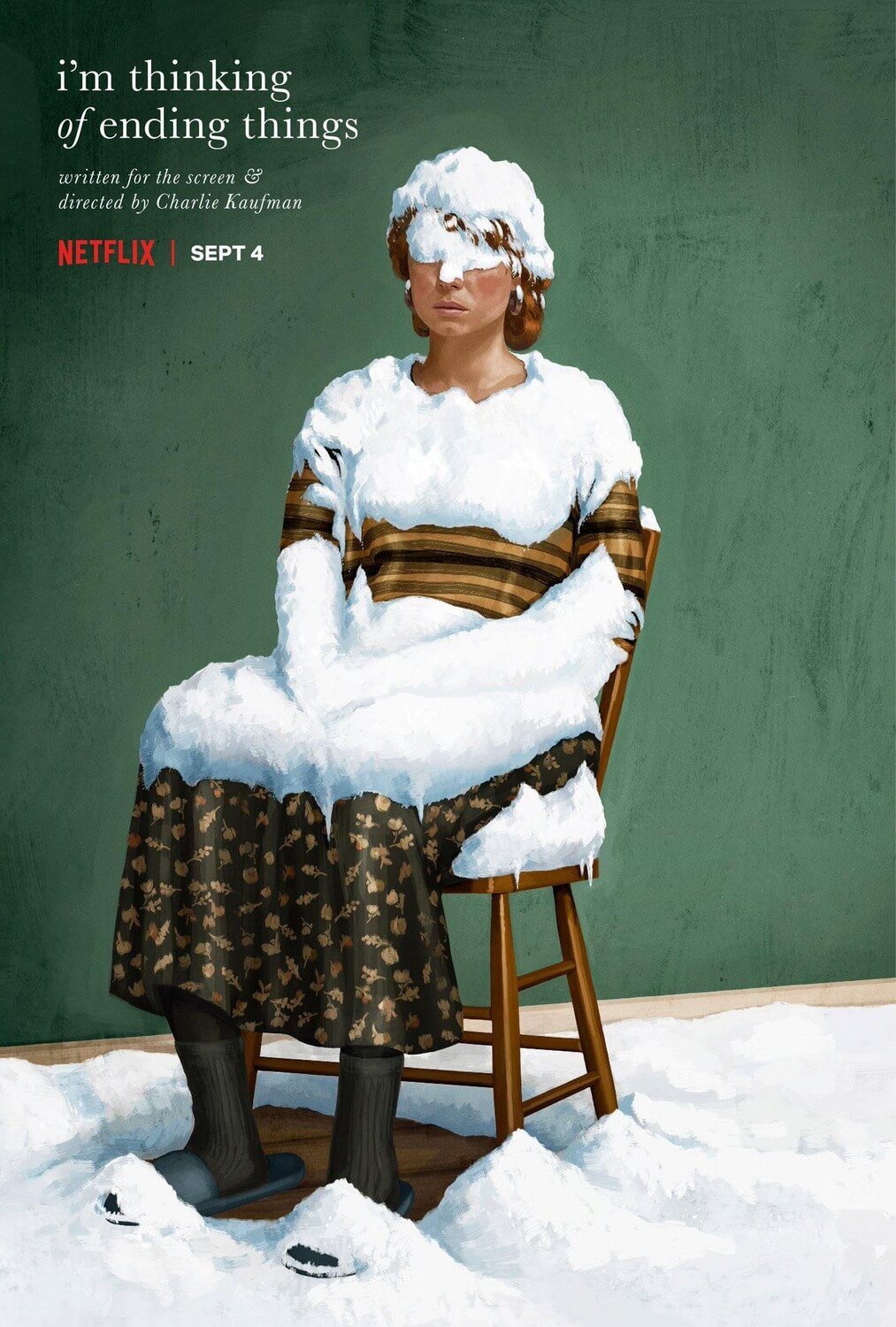

“It’s good to remind yourself that the world is bigger than your own head,” says Jake. The line comes early in Charlie Kaufman’s third film as writer-director, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, which he adapted from Canadian author Iain Reid’s 2016 novel. Depending on how you choose to interpret the story—and this is a film that, predictably, requires deciphering—Jake spends most of his time inside his head, disembodied from his routines as an elderly high school janitor. Jesse Plemons plays Jake in his younger years, but the actor’s appearance may just be a projection of the older man—spied briefly in intermittent scenes and played by Guy Boyd. The aged Jake’s mind wanders through his memories with an unstable grasp on time. But perhaps that’s revealing too much since most of the film remains with Lucy, played by Jessie Buckley, though her character’s name in the end credits appears as “The Young Woman.” Lucy might be the main character of this pensive, dour, and bewildering film; she may also be an amalgamation of Jake’s experiences with women—a mixture of lost opportunities, failed romances, and otherness that exists only in Jake’s mind. He tries to give her an internal life, but she remains outside of his mental prison, not entirely real. Like each of Kaufman’s screenplays, this one is about the egocentric struggle to escape your own head. At once an expression of interiority drawing from ideas swirling around in Kaufman’s brain and a self-loathing critique of that inwardness, I’m Thinking of Ending Things questions the extent to which we see each other as real.

This is a particularly timely subject, given that Kaufman’s film makes its debut on Netflix about six months after the first lockdowns due to COVID-19. When people see it, they will not watch it in a crowded theater with other human beings. Many will watch it alone, some with a cherished partner. Since the U.S. outbreak in March, some of us—those who decided to give a damn, anyway—have limited our social interaction with friends, family, and the public. Others are not so concerned. Meanwhile, elderly people make up most coronavirus deaths. Few seem to mind that more people could die; they would prefer to go maskless or continue to have birthday parties, even if it means someone’s grandparent will succumb. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, head of the World Health Organization (WHO), described the world’s apathy about elderly deaths from COVID-19 as a form of “moral bankruptcy.” Kaufman seems to acknowledge how, as we get older, we become increasingly less essential to others. We spend so much time trying to prolong our existence by dieting, exercising, and making healthy choices to extend our life, only to end up forgotten or thought of as an inconvenience. As one character puts it, our “terribly unkind” society is repulsed by the aged, fearful of how degenerative diseases like dementia will eat holes in our memory. I’m Thinking of Ending Things reminds us that inside the elderly person’s mind exists a lifetime of experiences, many of which we’re taking for granted.

Before we understand any of this, if the viewer can manage that, we seem to follow Lucy on a road trip to meet Jake’s parents for the first time. She’s thinking of ending her relationship with Jake, whom she’s been dating for six weeks. Or maybe she’s contemplating suicide. We hear her almost perpetual narration in these early scenes, and sometimes, Jake, driving the car, can hear this inner monologue. Throughout the drive, her mind wavers, and so does her character. Slight details about Lucy shift, not the least of which is her name. Jake calls her Lucia and Luisa at various points, which doesn’t seem to phase Lucy. She’s also hiding that someone named “Lucy” is calling her phone repeatedly, though she refuses to answer. Other discrepancies confound. She claims to study veterinary diseases; later, it’s physics, or maybe it’s painting—in any case, she cannot stay too long at Jake’s parents’ place because she has to return home to write a college paper. She also claims to despise poetry, but then she cries through a lengthy recital of her own poem (which is not her poem but one by Eva H.D.). For every inconsistency, which includes the color of her outfits, Kaufman establishes the film’s desperate attempt to make Lucy real, even though, like all writers, Kaufman merely accumulates details into a projection. What is anyone but the sum total of individual memories and personality traits that evolve over time?

Whether he feels compelled to cite William Wordsworth’s poem “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” or decries the narrow pop-awareness of David Foster Wallace’s suicide, Jake’s conversation with Lucy requires a certain literacy of artistic representation. But it’s also typical of a superior male perspective that Jake, a trivia nerd, holds his knowledge of such things over Lucy. He also corrects her, changes the subject when she asks a difficult question, or reacts with closed-off anger when he doesn’t get his way. You can feel Kaufman, through the aged janitor version of Jake, looking back at this behavior, seeing it through Lucy’s eyes, and recognizing its toxicity in a roundabout mode of self-reflection. Indeed, Jake’s behavior can be disturbing, filled with reticence and even violent outbursts in which he punches the steering wheel. He seems oblivious to the effect of his behavior in the moment, and as he looks back, you can sense the regret. Plemons commits to these moods, just as he performs the later musical numbers with impressive range. But through this blending of perspectives, Lucy—who makes a convincing argument for the rapey quality of the Christmas favorite “Baby It’s Cold Outside”— feels like a fully realized character only because Jake has seen himself as the problem.

Similar to his theme in the masterful Anomalisa (2015), in which Kaufman’s puppet protagonist saw everyone with a level of sameness that created a profound sense of alienation, Kaufman acknowledges the struggle to exist outside of life’s familiar and repetitive gestures. It’s an idea visualized by the patterned wallpaper in Molly Hughes’ production design, but also the obligatory conversations and social cues at the unusual dinner with Jake’s parents, played by Toni Collette and David Thewlis. If the chatter and intentional continuity errors in the car seemed strange, things get downright surreal at their destination, beginning with a haunting trip to the barn on the family’s property. Inside, away from the looming blizzard, Lucy enters a realm where Jake’s parents appear at various ages from young to senility, while Lucy struggles to remember how long they have been dating (“It feels like forever in a way,” she admits). His parents behave in the way young people see old people, as a series of odd and unnerving behaviors, heightened in Jake’s mind—and incredibly performed by Collette and Thewlis. The entire sequence at the house has the quality of a hilarious nightmare, complete with a dog that remains uncannily out-of-sight and out-of-mind, while something dreadful awaits behind the scratched basement door.

To be sure, I’m Thinking of Ending Things has been described as a horror film, an association loaded with expectations. It doesn’t quite meet the demands of the genre, but it does explore the grimness of reality and how people choose to avoid it. For instance, religion and cinema remain at the forefront of Kaufman’s mind. Each dilutes reality. “We watch too many movies,” Jake says, complaining that people prefer the escape of cinema in place of “seeing” people. Even so, Kaufman has made our knowledge of cinema an essential aspect of watching this film. One scene features Lucy acting out Pauline Kael’s review of A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Gradually, Buckley’s performance transitions from an impersonation of Kael to an embodiment of Gena Rowlands in that film, complete with her outta here gestures as Mabel Longhetti. This single sequence helps us better understand Lucy as a woman forced to inhabit the same space (even if it’s mental space) as her inconsiderate man. Yet, it also emphasizes how art helps us understand reality—a complex notion that both imbues the viewer with a greater capacity for empathy and creates a narrow, fictionalized filter through which they see the world. Kaufman pokes at the downfalls of fantasized cinema with humorous takes on movie musicals and the films of Robert Zemeckis (but apparently Kaufman hasn’t seen 2016’s Allied). If people see life as an imitation of art, Kaufman seems to argue, then they do not see life for what it is.

Kaufman recognizes the prison of the mind, and he yearns for his audience to consider the world beyond our subjectivity. It’s a theme he’s dealt with since his screenplay for Being John Malkovich (1999), where people paid big bucks to see the world through another person’s eyes. There is no objective reality, so we must gather as much subjective understanding as possible to further our knowledge of the world. Part of this subjectivity entails how we process time, a fluid and amorphous concept in Kaufman’s hands, both in his dialogue (“Do we move through time, or does time move through us?” asks Lucy) and his formal presentation. Much of the 132-minute runtime unfolds over three extended encounters—Lucy and Jake on the way to his parents’ house, their evening with his parents, and their long and episodic trip back. Although periodic interruptions occur, such as brief scenes with the elderly janitor. Kaufman makes us feel time in these passages, helping the viewer to not only process but acknowledge how time chips away at people. Matters of time and fading memory, and our willful dismissal of these concepts, become the substance of a film that asks us to avoid distractions and instead confront the brutality of everyday existence. It’s easy to overlook the harshness of reality with platitudes like “life can be difficult on a farm,” but the grim truth is that animals die on a farm, sometimes horribly. Take it from the cartoon pig, voiced by Oliver Platt, who died after being eaten from the inside-out by maggots.

If that sort of existential dread can be described as horror, then so be it. Kaufman’s presentation certainly evokes a state of spine-chilling surreality, beginning with cinematographer Łukasz Żal’s confining Academy aspect ratio. Kaufman has advanced from a mannerist screenwriter into a controlled filmmaker who has made every camera movement and every cut intentional and considered. Note the jagged quality of Robert Frazen’s editing, which suggests the disconnection between characters and the fragmentation of Jake’s mind, and how it isolates them. Or the set decoration, which reinforces the push-and-pull between our perception of life’s dull patterns and our unwillingness to see the humanity behind them. And the late-night detour at a roadside ice cream shop, called Tulsey Town (apparently Dairy Queen felt squeamish about being associated with this film), feels like something out of a bad dream. Ever self-reflexive and rooted in meta-commentary, Kaufman’s treatment considers how life is a “fast train to hell,” yet we too often attempt to leap off the train in a religious or artistic escape. These are lenses that distort how we see other people, often reducing their complexities into a few accessible characteristics. When Jake’s dad looks at one of Lucy’s landscape paintings (images pilfered from tonalist Ralph Albert Blakelock), he cannot feel anything without seeing someone in the frame. It’s a stark metaphor for how the average person views the world—unable to relate unless it pertains to them.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things is funny, bizarre, filled with terrific performances, but perhaps not entirely knowable—in the transfixing and delightful manner of most Charlie Kaufman films. Still, if one hopes to articulate its meaning from scene to scene, they must commit to a personal unscrambling of material, which is bound to resonate deeply. As for my interpretation explored above, I see a film with its mind on our limited capacity for self-awareness and empathy. It compels us to think outside of our own limited view and recognize that, even though we are alone in a physical space or the mental container of our mind, we must endeavor to see beyond these limitations. Too often, we fail to see others because of our own self-obsession. “I don’t think we know how to be human anymore,” someone says in the film, and it’s a statement that feels like a response to everything happening in the world today. I’m Thinking of Ending Things finds a character looking back on his life and acknowledging his own interiority, and while grieving for his error, he does nothing to escape his thoughts. Perhaps Jake is like his father, who looks forward to not remembering what he can’t remember. And yet, despite Kaufman’s hopeless assessment of society, his despairing and depressed film could serve as a prompt. Something about it brought to mind E.M. Forster’s sentiment: “Only connect.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review