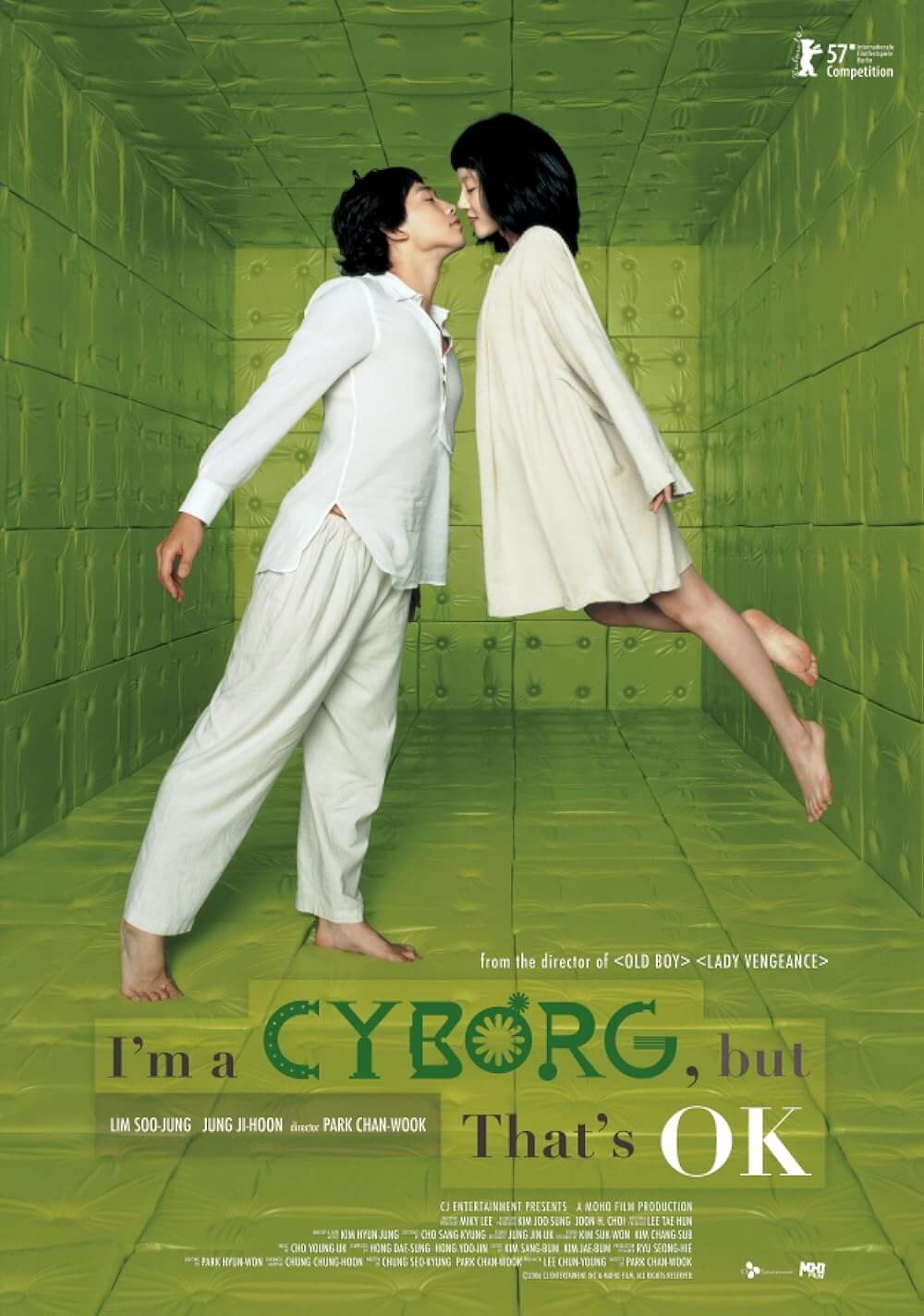

I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK

By Brian Eggert |

Films that take place inside mental institutions often begin with sane characters—someone who comes from a familiar, stable world and plunges into an unbalanced one. It’s the best way for storytellers to gain our sympathy and avoid drowning the audience under the surface of insanity. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest featured Jack Nicholson posing screwy to avoid duties at the workhouse. Bruce Willis confessed truths about a coming plague to psychologists skeptical about his ramblings in 12 Monkeys. And Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor offers a rational undercover journalist driven mad by his surroundings. Few films ever omit this safe entry point because the alternative is unrestrained lunacy.

South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook defies standards with every new film, so it should come as no surprise that in his latest effort, I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK, he refuses to comfort audiences with sane characters and thus an effortless viewing experience. Instead, aside from the background doctors attempting to maintain control over their hospital’s unhinged patients, the film’s story focuses entirely on the institution’s deluded, paranoid, compulsive, and hallucinatory patients. Taking this unconventional approach, he finds a curious sense of romanticism influenced by the imbalanced fantasies of his subjects.

But now you’re wondering about that title, trying to figure out what exactly being a cyborg has to do with mental institutions. Nothing, really. It’s just that Young-goon (Lim Su-jeong) believes she’s a cyborg, complete with machine guns hidden in her fingers. Young-goon’s family has a history of mental illness, as you might have guessed. One relative believed she was a mouse. Her grandmother was sent away for obsessively eating radishes, but she forgot her dentures when the caravan took her. Now Young-goon wears them, using them to speak to the hospital’s light bulbs and vending machine. (How else are machines supposed to hear you?) Perhaps you didn’t know, but cyborgs don’t eat food like you or me. Young-goon licks batteries during lunch while her meal is woofed down by a food-crazed inmate. Electricity is her only source of energy, something fellow patient Park Il-sun (Rain) notices straightaway.

Besides his standard kleptomania, Il-sun believes he can steal anything, including a person’s soul. He hops about in a rabbit mask, “stealthily” pilfering this and that. As a favor, he pinches one patient’s desire to do everything apologetically, nearly curing the man; meanwhile, another accuses Il-sun of stealing their ping-pong moves. What’s strange is how he uses his curse-of-a-talent to help Young-goon. She refuses to eat, and the doctors believe she’s suicidal. Maybe she is. Il-sun concocts a brilliant way of “operating” on her, using sound effects and touches on her back so she can’t see, to convince her that he’s installed a food-electricity converter. Now she can eat food, and her toes will light up with rainbow colors just like they’re supposed to.

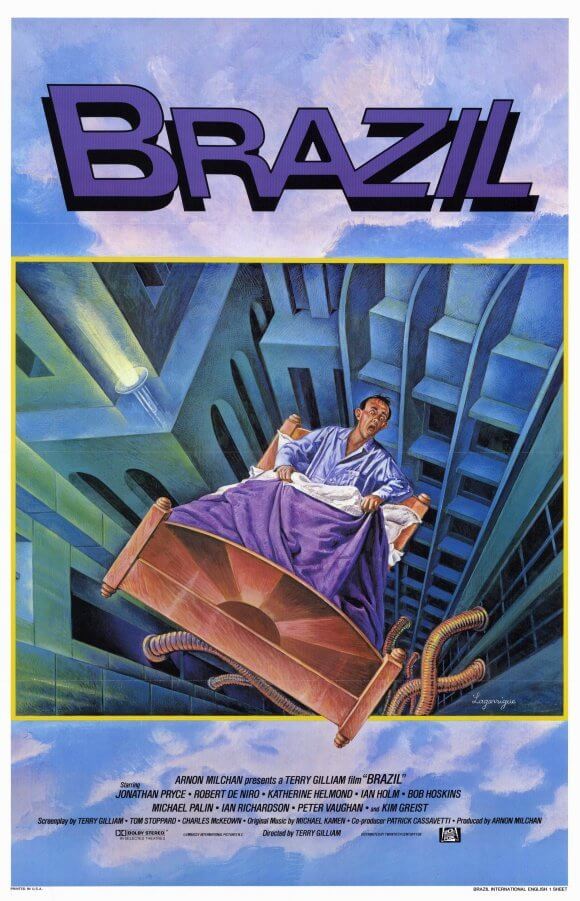

If this all sounds crazy, don’t be deterred. Identifying the film’s genre will prove troublesome because there are sad confessionals behind every patient, making each one a victim of themselves and their circumstances. There’s also an energy Park sews into every scene, imbuing them with bright colors, hilarious hospital nonsense occupying the background, and touching romance burgeoning throughout the picture. The closest comparison that comes to mind is The Fisher King, except without the sanity (and that I suggest one of Terry Gilliam’s films is “sane” should illustrate the potency of this picture). Indeed, romantic comedy elements combine with a lively fantasy, as Park floats away on long journeys into his patients’ dreams. Consider the simultaneous detail, dazzling composition, and joyful terror in the sequence where Young-goon shoots down the hospital staff with her nonexistent finger guns, her tongue reeling like an ammunition belt. Of course, this is a delusion. But oh, what a delusion!

Barely distributed in the United States, Park’s film bears modest resemblance to his previous efforts, speaking both in its visual palette and narrative. JSA: Joint Security Area (2000), and Park’s revenge trilogy of Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), Oldboy (2003), and Lady Vengeance (2005), each boast dark, grave, irresistibly engaging substance, full of drama and bloody tragedy. Profitable triumphs in his homeland, his earlier works made commercially viable imports when tagged as Tarantino-esque. Not so with his latest, whose returns disappointed, as the product is wholly offbeat and surely impossible to market. Given the unconventional, uncharacteristic result when compared to Park’s other films, I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK proves his style is all his own, no matter how American video companies want to advertise him. No release is planned on DVD, so film buffs should keep an eye on IFC’s television schedule or just cross their fingers. Panning for this singular little gem might prove strenuous, but the rewards are worth the effort.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review