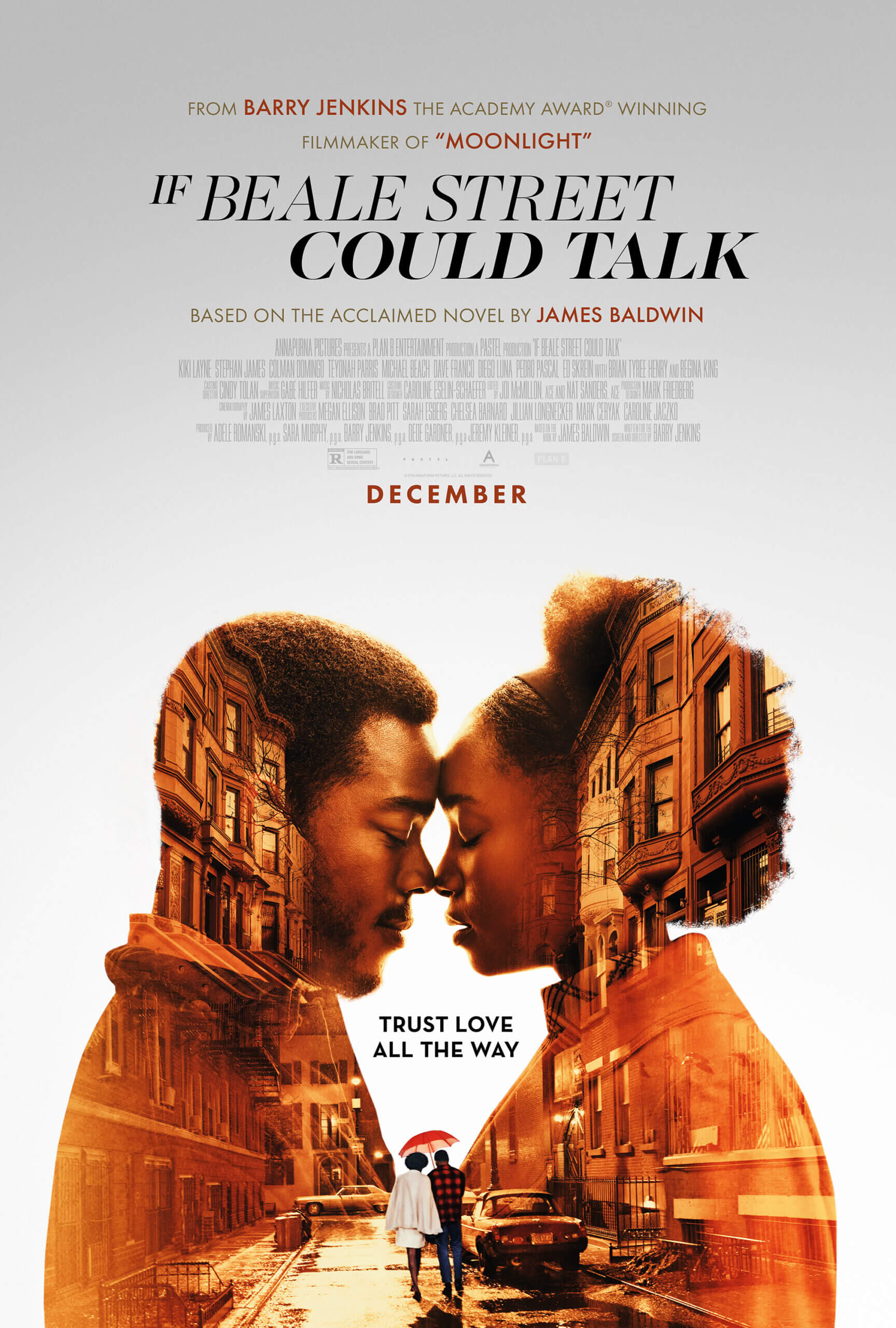

If Beale Street Could Talk

By Brian Eggert |

Barry Jenkins’ third feature, If Beale Street Could Talk, cannot help but draw parallels between its troubled Harlem setting in the 1970s and the present day. Based on the 1974 novel by the author and social commentator James Baldwin, the story follows a young woman whose future husband, the father of her unborn child, is wrongly imprisoned for a crime he did not commit. The film details the impossible struggle to prove his innocence while remembering, with a profound degree of humanist compassion, the beauty of the young couple’s pure love in hopeful possibility. Jenkins, just two years after his independent breakthrough Moonlight (2016) became an unlikely Oscar-winner, delivers another work of exquisite craftsmanship and artistry, once again drawing influence from the likes of Wong Kar-wai and Jonathan Demme. His picture details a corrupt system that robs African Americans of justice, jailing them inside of both prisons and their neighborhoods, while at the same time putting forth a loving ode to the people who endure despite the conditions around them. Although it sways toward social realism, Jenkins transforms the material into an expression of cinematic poetry.

Drawing from Baldwin’s novel for much of his screenplay, If Beale Street Could Talk begins as a period drama told from the perspective of Clementine “Tish” Rivers (KiKi Layne), the sometimes-narrator and protagonist. The 19-year-old discovers she is pregnant, but the child’s father, Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (Stephan James), Tish’s longest childhood friend, who has since become her lover, was just arrested on a bogus charge of rape. He is railroaded into prison by a corrupt cop with a beef (Ed Skrein), who arranged for the victim to select him out of a lineup. Now, the 20-year-old sculptor and future father must watch Tish’s pregnancy develop through glass. Those on the outside attempt to help. Tish and Fonny’s fathers (Colman Domingo and Michael Beach, respectively) try to raise funds for better legal representation—a well-educated white attorney (Finn Wittrock), who begins to realize the white-dominated system is stacked against his Black client. Meanwhile, Tish’s mother (Regina King) tries to speak with the victim, who has since disappeared.

Structurally, Jenkins intersperses moments from Tish’s memory into If Beale Street Could Talk’s rather hopeless aftermath following Fonny’s arrest, supplemented with her narration. We see the first time Tish and Fonny look at each other and realize there is something more beneath their longtime platonic friendship—complete with flashbacks-within-flashbacks of their shared bathtime as youngsters. We experience their untainted bond when they first make love or scout their first place together, seen through a gilded and dreamy frame, achingly romantic. Jenkins also flashes back to ominous moments, such as Fonny’s initial encounter with the white cop, who eventually frames him. Or take when Tish and Fonny serve a meal to Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry), a friend, who is fresh out of prison for reasons that foreshadow Fonny’s experience. The non-linear construction gives the viewer perspective on what has happened and why, though its application is occasionally inconsistent. For instance, most of the story is told from Tish’s perspective, accompanied by her voiceover—recalling the first-person singular style of Baldwin’s text. But other scenes, such as those involving Fonny’s attorney or Tish’s mother, seem to come from the filmmaker’s perspective.

Jenkins uses stylistic flourishes throughout the film that, alas, can have an occasional distancing effect. Although early scenes—such as when Tish tells her parents about the pregnancy, then they tell Fonny’s parents, and the situation becomes explosive—feel natural and even theatrical in their staginess, and the drama becomes more austere and deliberate as it unravels. The tone of If Beale Street Could Talk is predominantly melancholic and affected, treating the material with an artistic weight that reveals itself in the film’s form. Jenkins employs slow-motion for added gravitas, and Nicholas Britell’s crestfallen score renders these touching moments with undeniable heaviness. The director also overuses Demme’s signature shot—where a character looks directly into the camera. Whereas in The Silence of the Lambs (1992) or Philadelphia (1993), Demme used this shot to immerse the viewer into his character’s subjectivity, for Jenkins, who accompanies it with slow-motion or dialogue that now and then feels overwrought, it doesn’t have the same effect as its intimate use in Moonlight. However, when Tish visits Fonny at the prison, it’s potent and immersive.

“Don’t be scared,” Tish tells him in one of their face-to-faces. “Just remember that I belong to you.” Tender words such as this overwhelm the film’s artistic pretense, which occasionally distracts the viewer from the otherwise authentic, romantic, and tragic world of If Beale Street Could Talk. This is filmmaking that the viewer cannot help but notice throughout, sometimes to our appreciation of its self-consciously perfected refinement, sometimes to our sidetracked eyes. The characters have been shot in a beautiful array of golden hues captured by cinematographer John Laxton—who also filmed Jenkins’ other two features, Medicine for Melancholy (2008) and Moonlight. Caroline Eselin’s costumes appear in sharp yellows, bold reds, and deep greens, recalling something Todd Haynes might have assembled in an ode to Douglas Sirk. At the same time, everything onscreen is perfectly framed, arranged, and presented, resulting in a coldness at times—or at least an apparent self-awareness in its attempts at creating an arty warmth. The actors, however, are astoundingly sincere and human. The relative newcomer Layne is the film’s emotional core, but then everyone else onscreen inhabits their roles in earnest, deeply felt performances that counteract the film’s brief moments of stylistic embellishment.

If Beale Street Could Talk is ultimately a more significant parable than a love story. Baldwin meant Beale Street to be a cipher of the Black experience in America. Jenkins opens the film with a foreword by the author about his book in which he writes, “Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy.” In that sense, the story that unfolds reveals a shared set of commonalities that prove universal in their human toil. Jenkins adopts Baldwin’s humanist brand of elegiac drama to create something more than just a tale of an average Harlem family; rather, it is a social and political statement, as many Baldwin works are. Of course, the suffering and love on display throughout contain overwhelming moments of feeling, rendered with the filmmaker’s meticulous staging and application of form. His treatment has been constructed and performed with passion to spare. But the consequence of If Beale Street Could Talk extends further into the realm of allegory, and more than its depiction of love and endurance, the film’s message lingers at the forefront of the viewer’s mind.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review