Reader's Choice

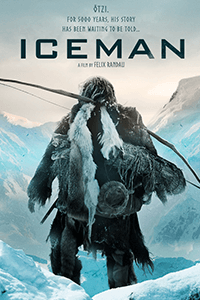

Iceman

By Brian Eggert |

Ötzi is the nickname given to a natural mummy discovered by two German hikers in 1991. Found frozen in the Schnalstal Valley glacier, amid the Ötztal Alps between Northern Italy and Western Austria, the Copper Age man was preserved in ice, clothed in furs, and armed with a copper axe. Researchers identified some 60 tattoos on his skin, an undigested meal in his belly, a wound on his head, and an arrow in his back. Ötzi has been the subject of intense scientific research and debate, though the consensus is that he’s over 5,300 years old. How he came to be so high in the mountains and why he was killed remain sources of informed conjecture, though forensics into pollen and other traces of evidence have revealed his birthplace, the region where he hunted, and his diet. Some archeologists hypothesize he was a high-altitude shepherd; others wonder if he was attacked and fled to the mountains to die. German filmmaker Felix Randau dreams up a potential scenario with his 2017 feature Iceman, an immersive and entertaining act of cinematic speculation, albeit limited by its simplistic plotting.

Iceman furthers the tradition of movies about prehistoric humans, including Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire (1981), Michael Chapman’s The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986), and most recently, Albert Hughes’ Alpha (2018). None of these examples have intricate narratives, but they each manage to be fascinating journeys into a time long ago, conveyed without discernible language but with an entrenched understanding of relatable human behavior—suggesting that, in thousands of years, we haven’t changed all that much. In Randau’s film, the characters speak in proto-Rhaetian, a language spoken in the eastern Alps and thereabouts in Europe. But never mind what they’re saying. An early title card informs, “Translation is not required to understand this story.” By necessity, then, Randau’s script keeps the narrative easy to follow, the characters communicating in basic needs and desires that, had subtitles been present, may have seemed rooted in clichés and trivialities. Randau also dabbles in exploitation genre tropes to keep his audience invested.

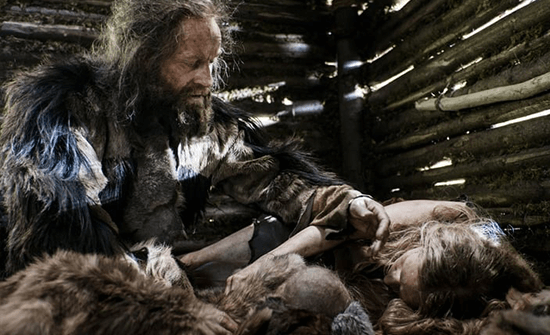

Indeed, the movie is not without a helping of sex, violence, and revenge. Randau first introduces Ötzi—credited under the name Kelab and played by German actor Jürgen Vogel—having sex with his mate, Kisis (Susanne Wuest), while their young son sits nearby, playing the flute. Modesty doesn’t exist yet, it seems. Then, in these early scenes, Kelab, who serves as some manner of chieftain, oversees the birth of a new child in their village, though the mother dies during childbirth. He and Kisis will adopt and raise the child in their two-family community, nestled in the foothills of the Alps, with modest huts, a bridge over the nearby river, and a fence that keeps pigs and goats. The plot kicks into gear when Kelab goes out hunting in the hills, checking traps and aiming his arrows at wild goats. Meanwhile, a rival group of three raiders launches an assault on Kelab’s village, leaving everyone brutally murdered and the huts burning. Kelab returns in a panic and, after recovering only the newborn and a goat, sets out to track down those responsible.

The narrative’s primal underpinnings don’t amount to much in terms of dimensionality or emotional range. And while Randau’s tale of single-minded revenge could have descended into a bloodthirsty B-movie, the violence seldom feels sensationalized or exaggerated to appease gorehounds. Rather, Iceman tracks Kelab on a straightforward journey to avenge his family, with few detours. Early on, he covertly attacks two bandits, believing them the culprits, only to discover he attacked the wrong people. At least the episode allows him to rescue a kidnapped young man who will return the favor in an unspoken life debt. A brief stop with an old hunter (Franco Nero) and his adult daughter or possibly a young wife (Anna F.) allows Kelab to offload the newborn and focus on his mission. Aside from a scene where Kelab feeds the child using a goat, Randau doesn’t show much interest in Copper Age child-rearing (for instance, Kelab never has to change a diaper). Eventually, he completes his journey over the mountain to exact his revenge, though he’s decidedly more humane to the women and children in his enemies’ village. Still, the viewer would be wise to remember Ötzi’s fate. Randau delivers a finale that recalls Carlito’s Way (1993), with the resident Benny Blanco from the Bronx showing up at the last minute to deliver a death blow.

The narrative’s primal underpinnings don’t amount to much in terms of dimensionality or emotional range. And while Randau’s tale of single-minded revenge could have descended into a bloodthirsty B-movie, the violence seldom feels sensationalized or exaggerated to appease gorehounds. Rather, Iceman tracks Kelab on a straightforward journey to avenge his family, with few detours. Early on, he covertly attacks two bandits, believing them the culprits, only to discover he attacked the wrong people. At least the episode allows him to rescue a kidnapped young man who will return the favor in an unspoken life debt. A brief stop with an old hunter (Franco Nero) and his adult daughter or possibly a young wife (Anna F.) allows Kelab to offload the newborn and focus on his mission. Aside from a scene where Kelab feeds the child using a goat, Randau doesn’t show much interest in Copper Age child-rearing (for instance, Kelab never has to change a diaper). Eventually, he completes his journey over the mountain to exact his revenge, though he’s decidedly more humane to the women and children in his enemies’ village. Still, the viewer would be wise to remember Ötzi’s fate. Randau delivers a finale that recalls Carlito’s Way (1993), with the resident Benny Blanco from the Bronx showing up at the last minute to deliver a death blow.

The production shot on location in the Italian Alps, capturing stunning scenery at real-life locations, from vast mountain range panoramas to expansive forests, from natural wildlife to narrow passages inside a glacier. Cinematographer Jakub Bejnarowicz uses digital cameras to shoot the action, which occasionally feels too modern or electronic a visual technique to feel in tune with the story. Then again, celluloid isn’t exactly an ancient technology either. Still, the handheld quality of the filmmaking recalls Mel Gibson’s approach on Apocalypto (2006), a similar tale of an ancient hero’s inevitable collision with history. In Iceman, the production design and costumes look as though much research went into them to ensure historical accuracy. But there’s little beyond appearances to consider. The movie’s singular narrative thrust is an adventure across rugged and deadly terrain, demonstrated when one of Kelab’s enemies falls from a cliff while trying to secure a better position from which to shoot arrows. Randau and editor Vessela Martschewski compose efficient, straightforward action that’s easy to follow and often thrilling to behold.

Although Randau doesn’t offer psychologically complex characters or personalities to cling to, his film confronts a few universal truths that suggest Iceman has a worldview or lesson to impart. For instance, the raiders in the opening seem to be interested only in a mysterious object, which Kelab worships and keeps in a wooden box, hidden from the viewer’s eyes like the suitcase’s contents in Pulp Fiction (1994), albeit without the glow. The shrine inside emboldens the connection between Kelab and his god, whom he shouts to more than once in lines that the viewer can reasonably interpret (“Why have you done this to me?!”). Randau confronts how one of the few constants of humanity is that people are willing to kill when one party wants something another has. Another prevailing theme suggests humanity’s basic need for vengeance perpetuates a cycle of violence that leaves only ruins. Of course, Randau wants to entertain, so his narrative is actionized to almost questionable extremes. However, traces of several other humans’ blood on Ötzi suggest that perhaps he was engaged in some epic altercation before his death, so the movie’s revenge-thriller mode of interpretation isn’t all that unbelievable.

Alas, a mystery is often more compelling than getting answers, and that rule applies to Ötzi and Iceman. Admittedly, I enjoyed reading about Ötzi in various scientific articles and on the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology (his current home in Bolzano, Italy) in preparation for writing this review more than I enjoyed watching Randau’s comparatively uncomplicated movie about his life. Randau includes a few small details that reference trace evidence left on Ötzi’s body, but the filmmaker’s speculations don’t amount to much. What we learn from Kelab and Ötzi is that humanity has always felt an innate need to invent absurd reasons to kill one another, take what’s not theirs, protect its family, seek revenge, and survive. The lessons aren’t exactly eye-opening, but the formal execution, contained within an efficient 97-minute runtime, is so compelling and attention-grabbing that it’s difficult to deny on those essential terms. Watching Iceman alone may illuminate, but it’s a worthy prompt to the internet rabbit hole that follows.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on January 7, 2024. Many thanks to Troy for requesting this review and for your Patronage!)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review