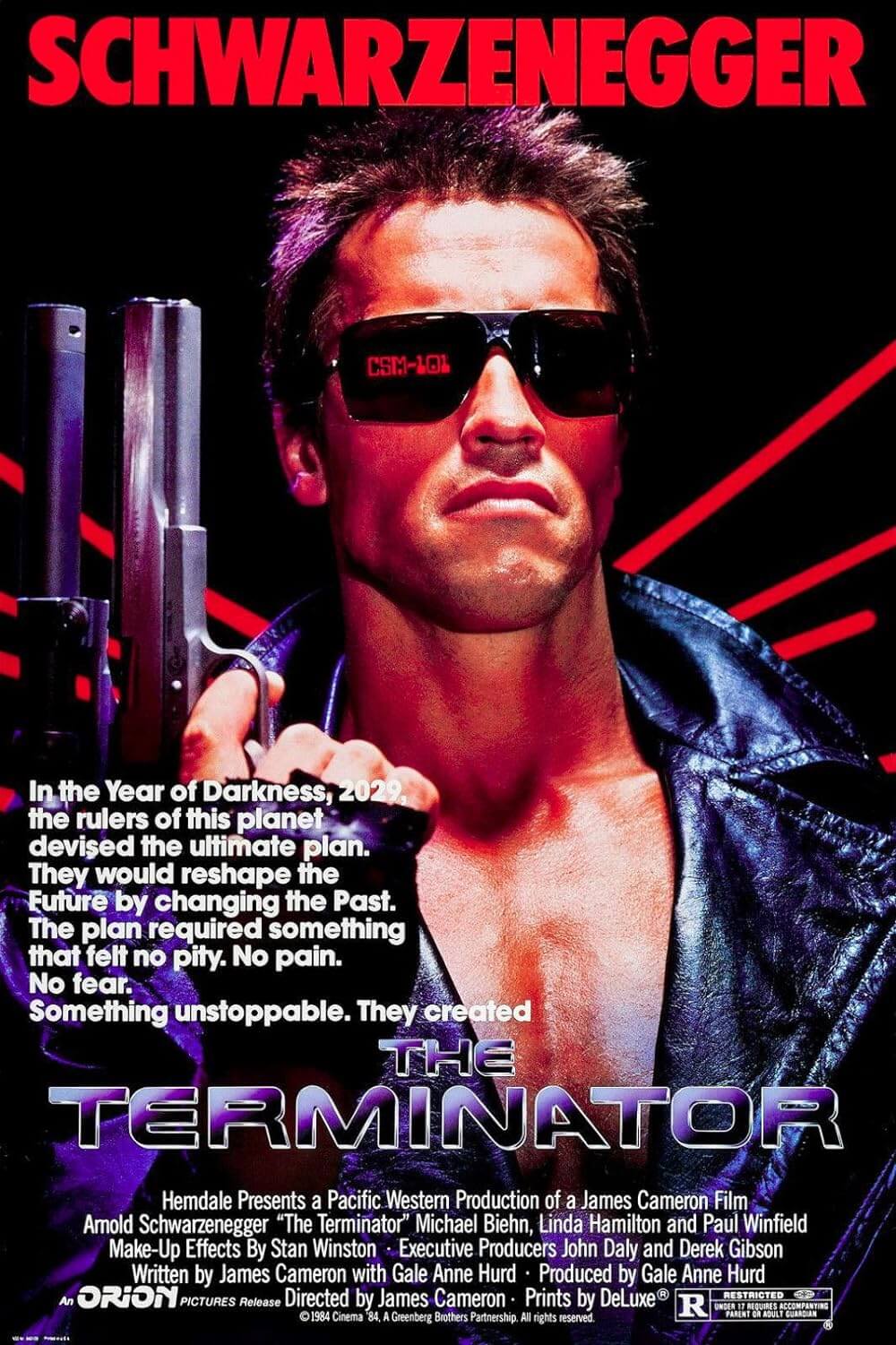

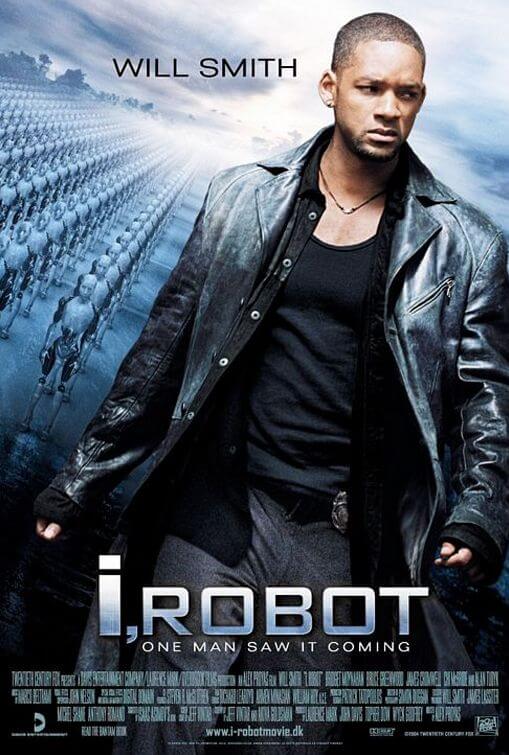

I, Robot

By Brian Eggert |

Alex Proyas made I, Robot in 2004 for Twentieth Century Fox when notorious executive Tom Rothman was running things, and after watching the film, the director’s name on the credits feels like an after-the-fact courtesy. Not only does this sci-fi blockbuster play like a studio-directed project in the worst ways, it’s evident onscreen and from the director’s remarks after the film’s release that Fox executives retained complete control over the product to assure it was commercially appetizing in every way possible. Though the material possessed the potential for landmark genre filmmaking, the result feels like two hours of product placement, so-so-special FX, too much comic relief, and non-acting from a star sleeping through his performance.

Set in the Chicago of 2035, the story follows the robo-phobic Det. Spooner (Will Smith) who pieces together a mystery involving the death of leading robot designer Dr. Alfred Lanning (James Cromwell). Spooner suspects a U.S. Robotics (USR) robot is behind Lanning’s death, which the company’s billionaire head Lawrence Robertson (Bruce Greenwood) claims is a suicide. But everyone knows robots are “Three Laws Safe”—the machines follow a strict code, written by Lanning, that prevents them from harming or being taken advantage of by humans. Along with USR scientist Susan Calvin (Bridget Moynahan), Spooner discovers “Sonny” (Alan Tudyk), a robot created by Lanning to experience emotion and defy the Three Laws. Could Sonny have killed Lanning? Spooner thinks so, even though everyone believes his hunch is crazy.

Robots in this world are metal shells with vacant expressions, used as a servant class by everyone, except Spooner of course. He hates them ever since one ripped off his arm when it rescued him from drowning. The newfangled units, called NS-5s, look more streamlined and have semi-transparent white skin; their yellow eyes appear on blank faces. All older models will be replaced by NS-5s in an economically absurd exchange program, and when it’s over there will be 1 robot for every 5 humans, each of them more lifelike and attuned to human needs. Except, Spooner isn’t fooled, not even by Sonny’s unique blue eyes or by the feelings he seems to have. Eventually, Spooner’s attention is driven elsewhere, as it becomes apparent someone at USR is trying to have him killed for snooping into the Lanning case. But when the robots start headhunting Spooner and attacking people on the streets, the hero realizes a much larger conspiracy is unfolding before him.

Derived from Isaac Asimov’s robot-themed stories like Little Lost Robot and The Evitable Conflict and named after one such collection, the screenplay for I, Robot had been a long time coming in Hollywood. Drafts dating back to 1995 had gone through a series of renamings and revisions, culminating with a final draft credited to Jeff Vintar and Akiva Goldsman. Vintar supplied the screen story, whereas Goldsman (of Lost in Space infamy) supplied the painful humor and cheesy action fodder needed for a Will Smith vehicle. Through it all, the story was reduced from a brainy murder investigation that never left the scene of the crime, to a sprawling, overblown actioner. Goldsman gave the mystery central to the film a lobotomy, added the necessary Will Smith-brand humor, and therein pleased the studio that wanted to twist a smart thriller into a blockbuster adventure.

What’s worse, somewhere along the line the film goes from being an adaptation of a classic science-fiction world into a two-hour commercial. Consider the first scene, where Smith’s Spooner wakes up and laces on his “vintage” 2004 Converse shoes, which he reflects on as “a thing of beauty”. (The only way it could be more obvious is if he looked into the audience and uttered “In stores now!”) Throughout the film, remarks are made about Spooner’s wonderful shoes, beating the audience over the head with the in-film advertisement. But let’s not forget about the rampant appearance of Audi, FedEx, and JVC within the film as well. This is the wrong way to do product placement. The right way to do product placement is as it appears in Minority Report, a sci-fi film from 2002 that cleverly uses its sponsors to incite a commentary about the dangers of futurist technology—Tom Cruise’s character in that film is made to transplant his eyes in order to avoid the ads’ incessant eye scanners, revealing product placement as a key plot device, to the extreme of the film critiquing its own sponsors.

But I, Robot is too busy flaunting its now-dull computerized effects, and being hip and funny for Will Smith’s sake, to concern itself with a social commentary. Smith is on autopilot here, indistinguishable from his characters in Bad Boys or Independence Day. The wise-crackin’ actor unloads his snarky lingo while blasting away robots in yawn-inducing, bullet-time action sequences, directed with post-The Matrix verve by Dark City helmer and Australian native Alex Proyas. The actors almost never look like they aren’t standing in front of a green screen, and the robots are about as three-dimensional looking as a cardboard standee. Even the film’s future-world design feels undeveloped, many of its elements lifted directly from Minority Report—including magnetic cars, holograms, and corporate corruption to advance new technology.

However, Proyas shouldn’t be held accountable for his directorial performance here, given the production’s sordid development history and the power struggles that occurred behind the scenes. Fox co-chairman Tom Rothman has earned himself a villainous reputation for turning potentially smart blockbusters into brainless duds (victims include the Alien, Predator, and X-Men franchises), and it’s no secret the same approach was given to this film, forcing Proyas to inject unnecessary humor (including a pointless comic relief role by Shia LaBeouf) into an otherwise thrilling setup. Proyas has since opened up and warned off fellow directors from working for Fox, saying he would “never again” subject himself to their employ after their meddling in this film. And even though I, Robot proved a financial success and demonstrated the marketability of another dumb Fox blockbuster, primarily due to the pop status of its star, the outcome borders on being unwatchably bad today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review