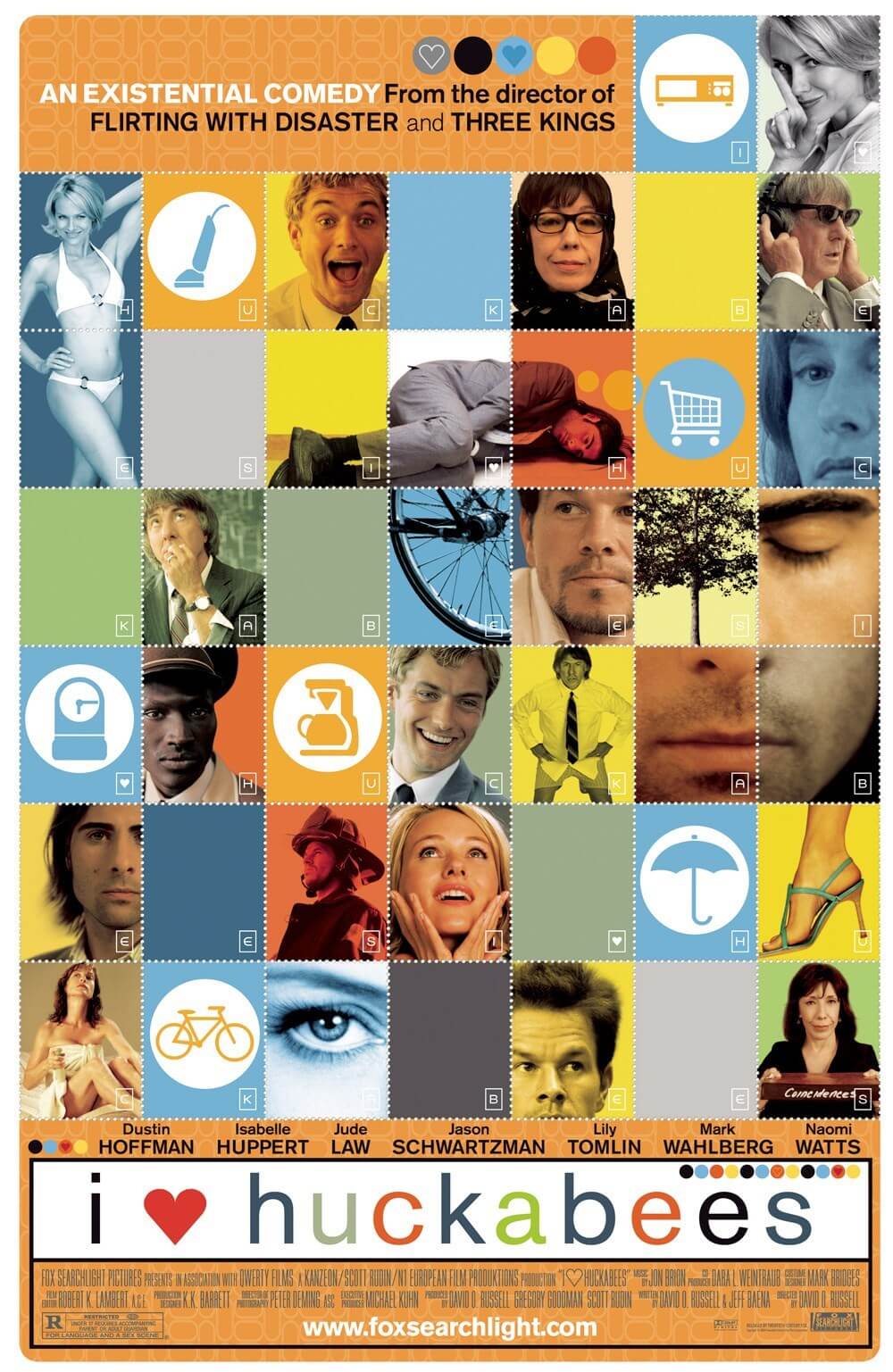

I Heart Huckabees

By Brian Eggert |

David O. Russell’s I Heart Huckabees epitomizes the love-it-or-hate-it film. Too thoughtful for audiences looking for lightweight entertainment and too filled with comic pandemonium to appeal to highbrows, this “existential comedy” has a select audience that can identify with the film’s continuous philosophical searching and still find the pleasures in Russell’s screwball construction. Here’s a film that, both in story and execution, is centered on the idea of finding order among chaos, and for viewers more accustomed to a tidy, straightforward narrative, the results can understandably seem like a helter-skelter experience. But there’s a method to Russell’s madness. Even amid idealistic discussions of capitalism versus liberalism or interconnectedness versus nihilism, there’s a surprising, level-headed middle ground at the core that makes the film strangely universal, if the audience is up for an existential trip.

Released in 2004, the film arrived five years after Russell’s lauded Gulf war masterpiece Three Kings, and eight years after Flirting with Disaster (the romantic comedy that solidified Ben Stiller’s “neurotic guy” persona). But Russell’s encouraging track record came to a halt here, as his unconventional film split audiences and critics alike—down the middle with a clean machete chop—leaving both sides convinced that what they’ve just seen is either utter nonsense or utterly brilliant. The terms “head-scratcher” and “disjointed” and “uneven” were used, whereas Rex Reed’s unkind New York Observer tirade remarked that the film “sinks to new depths of incoherent pretentiousness.” Overall, critics thought the film was a scattershot and preachy motion picture that failed to make a connection with its audience. In the minority, renowned critic and film theorist Andrew Sarris gave the film a rave review, calling it “a merry daisy chain of conflicting affinities linked together by Mr. Russell’s dazzlingly Ophülsian camera movements.”

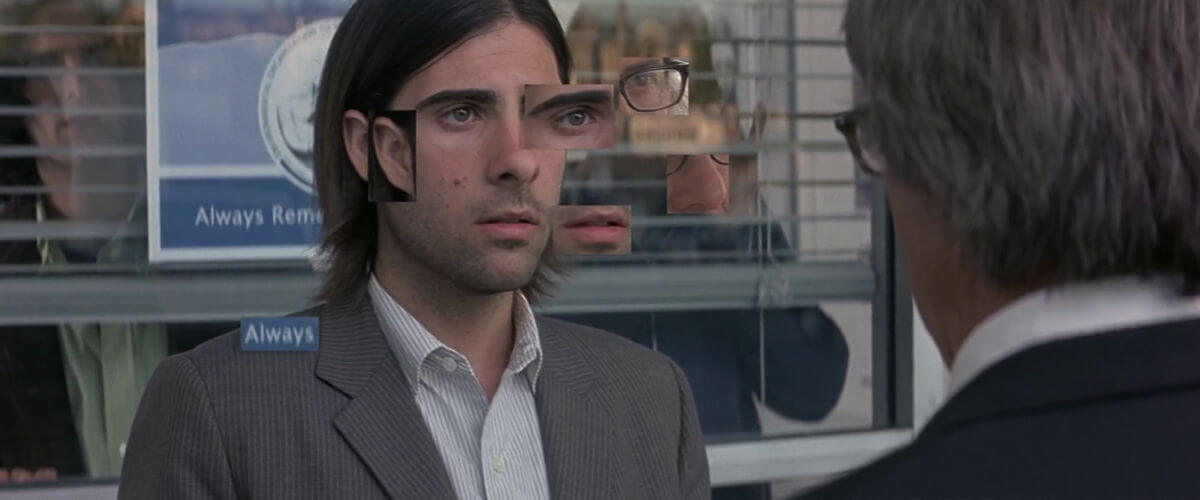

Much like Flirting with Disaster, Russell’s I Heart Huckabees is about the search for one’s identity. In one scene, the question is asked repeatedly: How am I not myself? The answer, of course, is that everything about you is part of yourself; thus, there is no such thing as not being yourself. But then, how can one be true to one’s Self when they are constantly growing and changing? By that logic, the idea of the Self does not exist at all at any point in time. There is no simple definition to the whole Self Question, as one is never either wholly one’s Self or wholly not. Are you following me so far? Perhaps I’m jumping ahead. Let’s begin where the film does, in the park, where Albert (Jason Schwartzman), a poet-environmentalist, has organized his environmental group to preserve a marsh and nearby woodlands from development from Huckabees, a Wal-Mart-esque retailer, represented by smooth-smoothy exec Brad Stand (Jude Law). Albert has questions, a lot of them, and for answers, he seeks help from “existential detectives” Bernard (Dustin Hoffman) and Vivian Jaffe (Lily Tomlin). Vivian asks him, “Have you ever transcended space and time?” Albert responds as the audience might: “Yes. No. Uh, time, not space… No, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Much like Flirting with Disaster, Russell’s I Heart Huckabees is about the search for one’s identity. In one scene, the question is asked repeatedly: How am I not myself? The answer, of course, is that everything about you is part of yourself; thus, there is no such thing as not being yourself. But then, how can one be true to one’s Self when they are constantly growing and changing? By that logic, the idea of the Self does not exist at all at any point in time. There is no simple definition to the whole Self Question, as one is never either wholly one’s Self or wholly not. Are you following me so far? Perhaps I’m jumping ahead. Let’s begin where the film does, in the park, where Albert (Jason Schwartzman), a poet-environmentalist, has organized his environmental group to preserve a marsh and nearby woodlands from development from Huckabees, a Wal-Mart-esque retailer, represented by smooth-smoothy exec Brad Stand (Jude Law). Albert has questions, a lot of them, and for answers, he seeks help from “existential detectives” Bernard (Dustin Hoffman) and Vivian Jaffe (Lily Tomlin). Vivian asks him, “Have you ever transcended space and time?” Albert responds as the audience might: “Yes. No. Uh, time, not space… No, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

In taking his case, Bernard and Vivian sell their positive-thinking solution: that all things in the universe are connected. Bernard illustrates this by comparing the universe to a blanket: The blanket represents all matter and energy in the universe, and as a result, we’re all connected. Vivian, on the other hand, spies on Albert to record events in his life, hoping to amass enough evidence to explain what irks him. More than anything, Albert wants to believe in their theories of interconnectivity because he’s grown obsessed with a series of coincidences in his life. When everything’s connected, nothing is a coincidence. To further elaborate on their theory as it applies to Albert, they partner him with his “other,” the intense firefighter Tommy Corn (Mark Wahlberg, never better). Lonely and abandoned, in Corn’s crisis, the world troubles him—everything from child labor in Third World countries to the global effects of using petroleum-based technology. Tommy questions why, with all the terrible things in the world, would someone want to believe that there’s a great order to it all? Instead, Tommy reads the works of nihilist Caterine Vauban (Isabelle Huppert), the ostensible nemesis and estranged pupil of Bernard and Vivian. She believes nothing is connected and the universe is anarchy, and hence meaningless. For Caterine, all one must do to live contentedly is manage their own human drama.

But Albert is plagued by human drama. His wild fantasies about chopping Brad’s head off with a machete surface in troublesome moments—realized through joyful meditation sequences filled with surrealist imagery—as does his fascination with Brad’s girlfriend, Huckabees’ spokesmodel Dawn (Naomi Watts). This leads to Albert and Tommy trying to escape their obsessions, hilariously so, by hitting each other in the face with a rubber ball until they zone out, during which time they feel a blissful nothing. This self-medicating solution is a temporary one suggested by Caterine, who answers many of Albert’s questions and turns both men to her side. Meanwhile, Brad continues to sabotage Albert’s professional life by taking over his coalition’s drive to “save the marshes,” endlessly selling the constituents pathetic power stories about his knack for selling Shania Twain on a chicken salad sandwich. In time, Brad hires Bernard and Vivian for himself, but only as yet another power play—or so he says. It’s more likely that Brad didn’t realize how closely Bernard and Vivian would look into his personal life, and he rejects them when their impression of him as a man desperate for approval proves none-too-flattering. Hiring Bernard and Vivian backfires on him when, after being exposed to existential probing, Dawn begins asking questions of her own; soon, she refuses to prance around in bikini tops anymore, resolving to live free from leering eyes under a bonnet and overalls.

But Albert is plagued by human drama. His wild fantasies about chopping Brad’s head off with a machete surface in troublesome moments—realized through joyful meditation sequences filled with surrealist imagery—as does his fascination with Brad’s girlfriend, Huckabees’ spokesmodel Dawn (Naomi Watts). This leads to Albert and Tommy trying to escape their obsessions, hilariously so, by hitting each other in the face with a rubber ball until they zone out, during which time they feel a blissful nothing. This self-medicating solution is a temporary one suggested by Caterine, who answers many of Albert’s questions and turns both men to her side. Meanwhile, Brad continues to sabotage Albert’s professional life by taking over his coalition’s drive to “save the marshes,” endlessly selling the constituents pathetic power stories about his knack for selling Shania Twain on a chicken salad sandwich. In time, Brad hires Bernard and Vivian for himself, but only as yet another power play—or so he says. It’s more likely that Brad didn’t realize how closely Bernard and Vivian would look into his personal life, and he rejects them when their impression of him as a man desperate for approval proves none-too-flattering. Hiring Bernard and Vivian backfires on him when, after being exposed to existential probing, Dawn begins asking questions of her own; soon, she refuses to prance around in bikini tops anymore, resolving to live free from leering eyes under a bonnet and overalls.

The way the story works itself out occurs in a free-form way, as the characters stumble upon the realization that neither ideology—connection nor disconnection—offers the correct answer. Rather, only through the process of searching for answers with an open mind does one attain the kind of nominal balance achieved at the end of the film. The path there may not be visible at all times, but the film hardly expects the viewer to dwell on structure; likewise, it does not want the viewer to know what to expect. Russell’s film arrived on the heels of Charlie Kauffman’s mind-bending scripts for Being John Malkovich (1999) and Adaptation (2002), and it’s the only film that achieves Kauffman’s otherwise unique brand of inspired imagery and intuitive characters within a narrative that tests known conventions of cinematic storytelling. Like Kauffman’s collaborations with director Spike Jonze, or his first writer-director outing with Synecdoche, New York, Russell’s film is indefinable as it is challenging and brilliant and funny.

Russell’s production employs polished camerawork and cutting; he fluidly moves between characters who flip-flop between schools of thought from one scene to the next, yet somehow retains a masterful control over the events and characters’ motivations. Along with his co-scripter Jeff Baena, Russell relied much on improvisation to drive the scenes as they do a bravado overlapping of dialogue. Characters finish each other’s sentences and carry on long, preachy tangents that are interrupted by Albert’s trippy dreams and otherwise peaceful moments of bike riding. But as much as Russell relies on improvisation on set, he demanded what some considered unreasonable control, insisting that the tone of a scene completely changes or that dialogue be said in a particular way, or that actors move to his precise instructions. Observe any scene from I Heart Huckabees, and it becomes evident that Russell is a director with a vision, but his treatment of his cast and crew has not always been spotless in the press. During the shoot on Three Kings, for example, he and star George Clooney engaged in fisticuffs, famously, when Clooney confronted the director about his unfair treatment of the cast and crew. Likewise, when Russell’s actors—most obviously Tomlin, as we know from YouTube—clashed with his approach, the resulting arguments made their way online, regrettably. Even offscreen, we see how Russell finds order out of chaos, and how not everyone is always on board for the experience.

Russell’s production employs polished camerawork and cutting; he fluidly moves between characters who flip-flop between schools of thought from one scene to the next, yet somehow retains a masterful control over the events and characters’ motivations. Along with his co-scripter Jeff Baena, Russell relied much on improvisation to drive the scenes as they do a bravado overlapping of dialogue. Characters finish each other’s sentences and carry on long, preachy tangents that are interrupted by Albert’s trippy dreams and otherwise peaceful moments of bike riding. But as much as Russell relies on improvisation on set, he demanded what some considered unreasonable control, insisting that the tone of a scene completely changes or that dialogue be said in a particular way, or that actors move to his precise instructions. Observe any scene from I Heart Huckabees, and it becomes evident that Russell is a director with a vision, but his treatment of his cast and crew has not always been spotless in the press. During the shoot on Three Kings, for example, he and star George Clooney engaged in fisticuffs, famously, when Clooney confronted the director about his unfair treatment of the cast and crew. Likewise, when Russell’s actors—most obviously Tomlin, as we know from YouTube—clashed with his approach, the resulting arguments made their way online, regrettably. Even offscreen, we see how Russell finds order out of chaos, and how not everyone is always on board for the experience.

Still, Russell has cajoled some incredible comedic performances throughout his career, and he holds an almost exclusive reign over Wahlberg’s best roles in their three collaborations (Russell also directed 2010’s The Fighter, which, in writing of fine performances in Russell’s film, won its co-star Christian Bale the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor). In I Heart Huckabees, Wahlberg’s fiery performance steals the show; his out-of-left-field outbursts and rants about petroleum are nothing short of side-splitting. But Naomi Watts finds an unexpected comedic voice when Dawn gives up her model lifestyle for a bonnet and proposes a new “truth” ad campaign where her spokesperson flops about the screen like a child impersonating an elephant. Jude Law, too, uses his good looks to play a singularly goofy, repressed character—a superficially confident executive motivated by jet skis and cutouts of Shania Twain. His performance is incredibly nuanced, as Brad is both arrogant and desperate for approval, and then later must manage a crumbling ego.

Though the film’s simplification of theories—ranging from the likes of Camus to Nietzsche to Sartre—may ultimately feel like Philosophy 101 to those who’ve studied these ideas, the ideas themselves prove all the more thought-provoking in the comedic context, in no small part due to the performances and the actors’ willingness to appear in absurdist situations. Consider Albert’s hallucination where he imagines Brad as a motherly figure; Law appears in a Goldy Locks wig, his man-mammaries oozing breast milk that’s being slurped up by a suckling, baby Albert who cries “mama.” Try ever forgetting that image. Later, the film boasts easily one of the strangest, least erotic sex scenes ever put to celluloid when Albert and Caterine run off into the marsh and proceed to dip each other’s faces in the mud, rubbing dirt over each other and then having sex in the muck. Add to these moments Wahlberg’s crazed appearance and Watts’ extreme frump factor as she remarks, “You can’t deal with my infinite nature, can you?” with a mouthful of brownies, and one must reflect with delight on the several memorable, clever, and crazily funny scenes littered throughout the film.

Though the film’s simplification of theories—ranging from the likes of Camus to Nietzsche to Sartre—may ultimately feel like Philosophy 101 to those who’ve studied these ideas, the ideas themselves prove all the more thought-provoking in the comedic context, in no small part due to the performances and the actors’ willingness to appear in absurdist situations. Consider Albert’s hallucination where he imagines Brad as a motherly figure; Law appears in a Goldy Locks wig, his man-mammaries oozing breast milk that’s being slurped up by a suckling, baby Albert who cries “mama.” Try ever forgetting that image. Later, the film boasts easily one of the strangest, least erotic sex scenes ever put to celluloid when Albert and Caterine run off into the marsh and proceed to dip each other’s faces in the mud, rubbing dirt over each other and then having sex in the muck. Add to these moments Wahlberg’s crazed appearance and Watts’ extreme frump factor as she remarks, “You can’t deal with my infinite nature, can you?” with a mouthful of brownies, and one must reflect with delight on the several memorable, clever, and crazily funny scenes littered throughout the film.

But the question of the film isn’t whether viewers will laugh at the joyfully outlandish sense of humor; it’s whether they can put together how those scenes are more than just brief off-the-wall imagery employed for a laugh. They are character-deepening clues embedded with double meanings and subtexts to be second-guessed and psychoanalyzed on repeated screenings. The test put to I Heart Huckabees’ viewer, strangely enough, becomes the same one put to the characters within the film—to embrace that everything in the film is both interrelated and disorderly, to make connections and find significance by piecing together one’s own purpose through the various existential principles on display. Watching the film, an audience must lose themselves in this deceptively controlled experience, only to find their way back again. Of course, not all audiences or critics are up to Russell’s challenge, which solidifies its status as a love-it-or-hate-it film. I Heart Huckabees is not for viewers who like to shut off their brains and watch, but rather for those who see the film as an ongoing investigation of elements that contain many momentary, metonymic rationales, yet also form into a larger, rather profound metaphor.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review