I Am Love

By Brian Eggert |

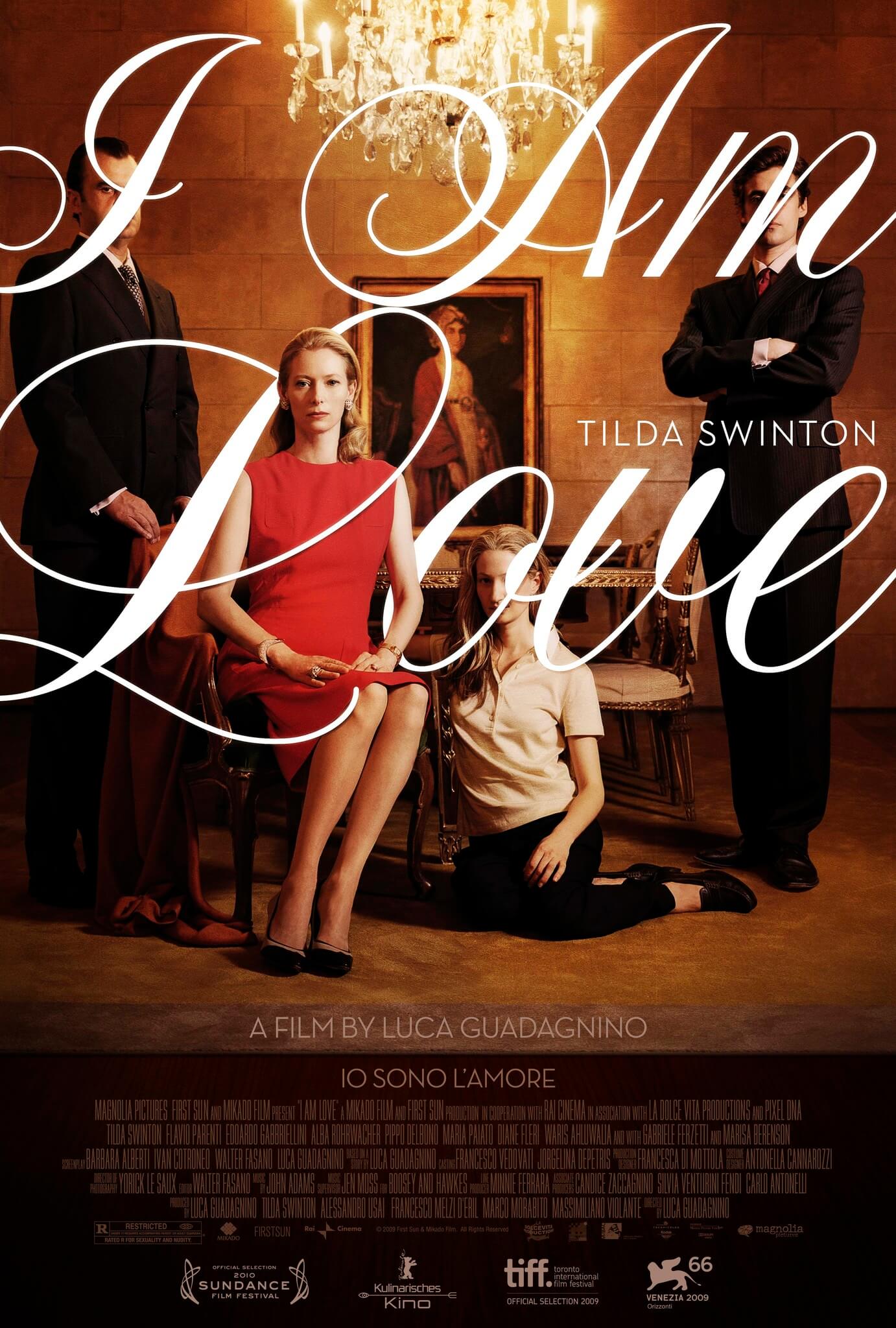

When the daughter of a Russian art dealer married into the Recchi family, a prominent textile empire based in Milan, she was told she must give up her Russian name and go by Emma. In a soaring embodiment-of-a-performance by Tilda Swinton, Emma finds herself amid Italian aristocrats bent on the tradition of wives being treated as outsiders in their own homes. For her, it’s even worse that she’s Russian, as valid emotions are often waved off as a sign of her nationality. As the wife to the family’s next in line, she may have a place among the highest of the Recchi clan, but after reformatting her lifestyle to become an Italian, she was long ago stripped of her identity.

I Am Love is an Italian film about the reclaiming of one’s Self, about casting away traditions that were preserved merely to preserve traditions. But it’s also a film ‘about’ embracing now unfashionable approaches to cinema established by great European filmmakers of yesteryear. Luca Guadagnino’s film values aesthetics as much as it dwells in the plight of its protagonist. The operatic production expects its audience to respond to theatrics, bright colors, lush details, and the swelling score by John Adams. The film wants to immerse the audience through the story, of course, but more so through the visual and auditory language of the entire mise-en-scène. It demands an audience that desires sumptuousness in their cinema, complete with bravado camerawork and meaningful, metaphoric passages to dissect.

The film’s opening scenes recall the Christmas party that opens Fanny and Alexander or the wedding reception that begins The Godfather, as the same prosperous sense of aristocratic excess and time-honored custom exists in the Recchi household. All have gathered for the birthday dinner of the aging patriarch, whose son and Emma’s husband Tancredi (Pippo Delbono) is announced as the successor, but only in a joint partnership with Emma and Trancredi’s eldest son, Edo (Flavio Parenti). “It will take two men to replace me,” he explains. The younger adult children, Betta (Alba Rohrwacher) and Gianluca (Mattia Zaccaro), have since moved on, so Emma remains at home, relating more to her long-serving domestic Ida (Maria Paiato) than her husband. When daughter Betta confesses to her mother that she’s a lesbian and in love, Emma reacts not with motherly disquiet, but with the curiosity of a good friend; Betta’s evident passion rouses Emma’s envy for such love. If only she could feel that way.

Enter Edo’s chef friend Antonio (Edoardo Gabbriellini), a divine cook whose dreams of opening his own restaurant will be realized by the leading Recchi son. Antonio’s inspired prawns and vegetable dish sends Emma into food ecstasy, igniting the awakening notion that her life could be filled with so much more than near-fascist Recchi customs. As she experiences more of Antonio’s food, she grows fascinated with him; infatuated even. There’s a splendid sequence where Emma—her hair in a spiral bun like Kim Novak in Vertigo, a microscopic but clever detail that suggests her romantic obsession—follows Antonio on the streets of Nice until they collide. He takes her back to his secluded country garden and passionate lovemaking follows talking and cooking. Afterward, in her bathroom mirror at home, she thinks of her encounter and beams a smile of unbridled jubilation. Though she has smiled much in the film at this point, it was often out of politeness or manners in her wife role; this is the first time we see the character smile and believe the expression is genuine.

Speaking pitch-perfect Italian and the occasional Russian, Swinton disappears into her rather beguiling role, which is all the more remarkable considering her androgynous performances in the past. She dons the finest clothes and carries herself with such elegance in the film’s first half, that when Emma begins to take hold of her life in the second half, Swinton’s transformation becomes representative of the actress’ impressive versatility. Her appearance, those high cheekbones and pale blue eyes spaced wide, often place a curious distance between the viewer and her character. She’s a difficult actress to figure out because of her unique and strangely fascinating appearance. And yet, here she gives a surprising and sensual performance, and she involves the viewer on raw emotional levels that build until the striking, operatic finale.

Speaking pitch-perfect Italian and the occasional Russian, Swinton disappears into her rather beguiling role, which is all the more remarkable considering her androgynous performances in the past. She dons the finest clothes and carries herself with such elegance in the film’s first half, that when Emma begins to take hold of her life in the second half, Swinton’s transformation becomes representative of the actress’ impressive versatility. Her appearance, those high cheekbones and pale blue eyes spaced wide, often place a curious distance between the viewer and her character. She’s a difficult actress to figure out because of her unique and strangely fascinating appearance. And yet, here she gives a surprising and sensual performance, and she involves the viewer on raw emotional levels that build until the striking, operatic finale.

But this says nothing of Guadagnino’s direction, which evokes a deep immersive quality through his gorgeous, artistic presentation. This is a stunning-looking film, shot with fluid camerawork by cinematographer Yorick Le Saux. It’s also exceptionally affecting. Guadagnino gives full submission to the extravagant Recchi world, enough so that we could lose ourselves in the rich meals, refined clothes, and lovely fixtures abound. Recalling Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard or Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence, the camera stops to regard paintings and lingers on food that we can almost taste. More than the surfaces, however, Guadagnino perfectly captures the emotions of every moment with equal parts class and artistry. Swinton’s performance can take much of the credit for the film’s impact, but there are also the generous flourishes that lend common melodrama moments—such as love scenes—poetic admiration over fetishist misuse.

It would be easy to dismiss I Am Love as pretentious, as a work of self-indulgent European melodrama (a common criticism of the film that assumes that melodrama is a negative trait, which it is not). How simple it would be to pick apart Guadagnino’s evident inspiration from the great directors referenced above (Bergman, Coppola, Hitchcock, Scorsese, and Visconti), attributing which scenes align with which classic film. How easy it is to dismiss all things melodramatic as negative, as some critics often do. But for the right audience, there’s a particular joy attached to this kind of filmmaking that harkens back to an era where Europe’s directors explored expressiveness and richness as a style. There’s a definite pleasure in high melodrama, the type of Visconti and Douglas Sirk, that doesn’t exist in films today. And now, filmmakers who approach melodrama without a sense of camp or irony are rebuked in their efforts for being “self-indulgent”. But what filmmaker doesn’t retain a level of pretentiousness by draping their style or lack thereof onto their production? If only more would indulge the emotive aspirations that Guadagnino conveys here, audiences might again find themselves attuned to grand emotions and style, instead of today’s sad over-reliance on ‘realism’.

There’s an unfortunate trend among both modern directors and film critics where ‘artsy’ expression and big emotions are viewed as problematic. If that is your opinion, then avoid I Am Love. For all others, here’s a film whose direction alone is worth getting thrilled about. The picture may not claim a lofty runtime to make it a sweeping dramatic epic in the sense of Fanny and Alexander or The Leopard, but it contains enough emotional substance and visual bravura to make the experience an intimate and stirring one. Words in this review such as “poetic” and “lavish” don’t begin to fittingly describe Guadagnino’s production, nor do “impressive” or “remarkable” properly describe the power of Swinton’s incredible performance. Suffice it to say that once the film grabs hold, it’s easy to admire, and for the right audience, easy to adore.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review