Hugo

By Brian Eggert |

In Hugo, Martin Scorsese takes us on an adventure to rediscover the origins of cinema. In doing so, he employs the latest cinematic techniques, including gorgeous special FX and the use of 3D, to bridge the gap between classic and modern films. Based on the book The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick (a relative of legendary producer David O. Selznick), the script by John Logan, who also wrote Scorsese’s The Aviator, includes an affectionate nostalgia for the magic of early moviemaking, whose progenitors were both artists and masters of technological trickery. As Scorsese demonstrates, they still are. Aligning his narrative ambitions with his prominent call for film preservation, Scorsese’s Dickensian children’s tale may, at first, seem like an unlikely picture for the director; however, as the story progresses and its themes emerge, it’s evident this is his most personal effort in years.

The film’s narrative follows a young boy, Hugo (Asa Butterfield), who almost never leaves the walls of a 1930s Paris train station. He scurries through hidden passages, up and down ladders, and along catwalks to manage the station’s clocks in perfect time, checking and oiling gears in the clockworks, just as his drunkard uncle (Ray Winstone) instructed him. Hugo is the station’s secret Quasimodo, who gazes out at Paris and sees a massive machine at work and then imagines himself as a crucial cog in that machine, but to what purpose? Abandoned by his uncle, Hugo survives by just scraping along, snatching food from station vendors, and narrowly avoiding the resident inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen, in a Tati-inspired performance). His routine is interrupted when an ill-tempered toy shop operator (Ben Kingsley) catches him taking a mechanical mouse; Hugo needs the parts to fix the automaton left to him by his late father (Jude Law). Within this elaborate wind-up doll hides a secret, and Hugo believes uncovering the secret will bring him closer to his father.

The old man allows Hugo to work off his multiple thefts by sweeping up the toy shop, and in turn, he helps develop the boy’s skill for mechanical devices, as well as card tricks. Hugo also meets Isabelle (Chloe Grace Moretz), who’s been raised by the old man and his wife (Helen McCrory). A bright girl with a large vocabulary and appetite for adventure from reading books, Isabelle joins Hugo in his search to uncover the automaton’s mystery, and he, in turn, introduces her to movies, taking her to the Harold Lloyd classic Safety Last. What they discover, thanks to the help of an early film historian (Michael Stuhlbarg), is that Isabelle’s guardian is none other than George Méliès, the former illusionist-turned-filmmaker who made hundreds of short films, including the iconic A Trip to the Moon (1902), in which a rocket crash lands into the Man in the Moon’s eye. Moreover, they learn the automaton belonged to Méliès, but its secrets reveal something far more substantial.

The old man allows Hugo to work off his multiple thefts by sweeping up the toy shop, and in turn, he helps develop the boy’s skill for mechanical devices, as well as card tricks. Hugo also meets Isabelle (Chloe Grace Moretz), who’s been raised by the old man and his wife (Helen McCrory). A bright girl with a large vocabulary and appetite for adventure from reading books, Isabelle joins Hugo in his search to uncover the automaton’s mystery, and he, in turn, introduces her to movies, taking her to the Harold Lloyd classic Safety Last. What they discover, thanks to the help of an early film historian (Michael Stuhlbarg), is that Isabelle’s guardian is none other than George Méliès, the former illusionist-turned-filmmaker who made hundreds of short films, including the iconic A Trip to the Moon (1902), in which a rocket crash lands into the Man in the Moon’s eye. Moreover, they learn the automaton belonged to Méliès, but its secrets reveal something far more substantial.

The film’s incorporation of actual film history into this fantastical story brings a sense of wonderment to any film aficionado, particularly when Scorsese details Méliès’ career, complete with recreations of Méliès’ sets and filmmaking process. Méliès had been hugely successful for a number of years until the Great War, when his cinematic reveries were no longer popular; after he went bankrupt, he was forced to sell his film stock to a company that melted down the celluloid and used it to produce the heels of women’s shoes. For years, his films were thought lost and the man himself was believed dead until Méliès was discovered working in a toy shop, at which point his films became the subject of a vast restoration project. Today, more than 175 of Méliès’ short films survive.

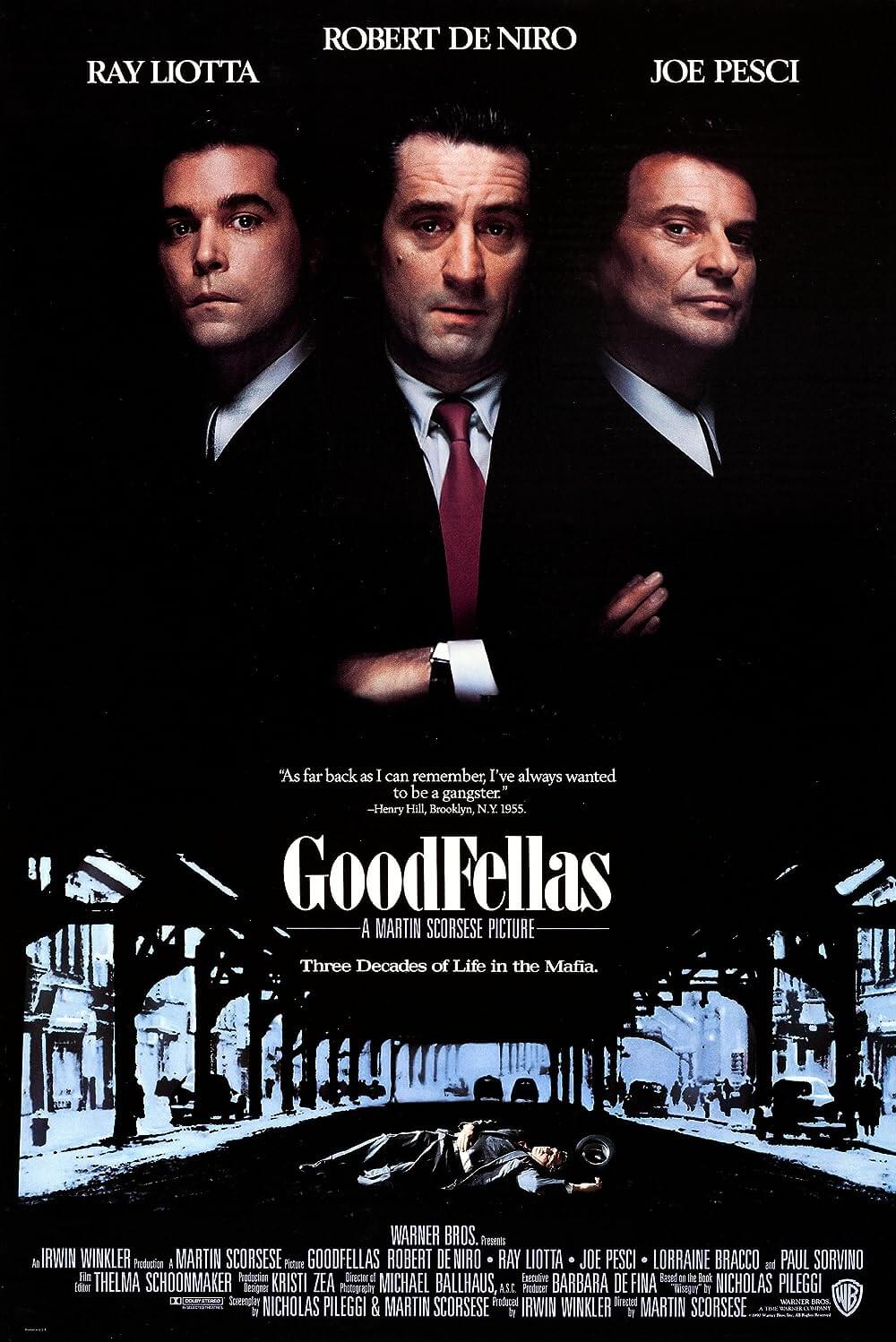

It’s not difficult to understand why Scorsese was drawn to the story, no matter how atypical a PG-rated family film may seem for the director of Goodfellas and Taxi Driver. There’s an autobiographical parallel here, as the young asthmatic Scorsese grew up looking out windows in Little Italy, his chief amusement being the local moviehouse. His earliest passions for watching images projected on a screen in a darkened room haven’t waned a bit; today, Scorsese’s love of cinema is just as enthusiastic, having founded The World Cinema Foundation, an organization dedicated to preserving films. Much like Hugo does with Méliès, Scorsese’s efforts have saved classic films from being destroyed, as well as rekindled newfound interest in forgotten filmmakers, such as Michael Powell. It doesn’t take long for anyone familiar with Scorsese’s personal history to see the director’s face in our young Hugo.

What’s more, Scorsese’s love of cinema as a magic-making device feeds a major theme in Hugo. He lovingly recreates a screening of the earliest film, the Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896), during which audiences ducked in terror as the train approached the camera. Scorsese recognizes that early filmmakers were not only technicians but illusionists, a group that had always sought the latest technology to augment their spectacle. For filmmakers like Méliès, this was the next logical step forward from sawing a woman in half. Méliès employed trick editing and hand-painted film cells to create illusions for his audiences and found that instead of magic, he was recording our dreams and playing them back for us. Today, filmmakers use CGI and 3D glasses to deliver such illusions, but the dreams themselves haven’t changed.

What’s more, Scorsese’s love of cinema as a magic-making device feeds a major theme in Hugo. He lovingly recreates a screening of the earliest film, the Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896), during which audiences ducked in terror as the train approached the camera. Scorsese recognizes that early filmmakers were not only technicians but illusionists, a group that had always sought the latest technology to augment their spectacle. For filmmakers like Méliès, this was the next logical step forward from sawing a woman in half. Méliès employed trick editing and hand-painted film cells to create illusions for his audiences and found that instead of magic, he was recording our dreams and playing them back for us. Today, filmmakers use CGI and 3D glasses to deliver such illusions, but the dreams themselves haven’t changed.

For the production, Scorsese gathered his usual team of wizards to achieve breathtaking craft and technical daring, and together his crew brings vivid life to the train station and its assorted characters. Robert Richardson’s cinematography captures Sandy Powell’s rich costumes in magnificent detail; the colors are vibrant, and the atmosphere dreamlike. But also there is romance. This is a storybook Paris, after all. Adorable subplots involving various station employees blossom, including one between Baron Cohen’s snooty inspector and Emily Mortimer’s flower girl Lisette, and another between an aged merchant (Richard Griffiths) and a bakery owner (Frances de la Tour). Scorsese’s production transports us into another time and place designed, in part by Dante Ferretti’s gorgeous production and Rob Legato’s visual effects, to romanticize in such a way that renders this film a Méliès-esque fantasy.

Hugo will enchant bright young moviegoers and adults hungry for a sophisticated viewing, and audiences will respond to a greater degree if they already have an appreciation for early cinema. 2011 has been a landmark year for films “about” film; Scorsese’s film heads Rango and Super 8 as the best of them. This is the stuff of film history and appreciation, a deeply felt ode from Scorsese to the filmmakers who continue to inspire him. To watch the wonder in young Butterfield’s eyes as images flicker on the screen of a Parisian cinema is to see Scorsese still in love with films and film-making. And yet, Scorsese has done today’s young film-goers a major service by captivating them as much as A Trip to the Moon must have enthralled viewers upon its debut. In its own way, more even than addressing Méliès’ history within a fictional story, Scorsese preserves film by delivering a picture that will not soon be forgotten.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review