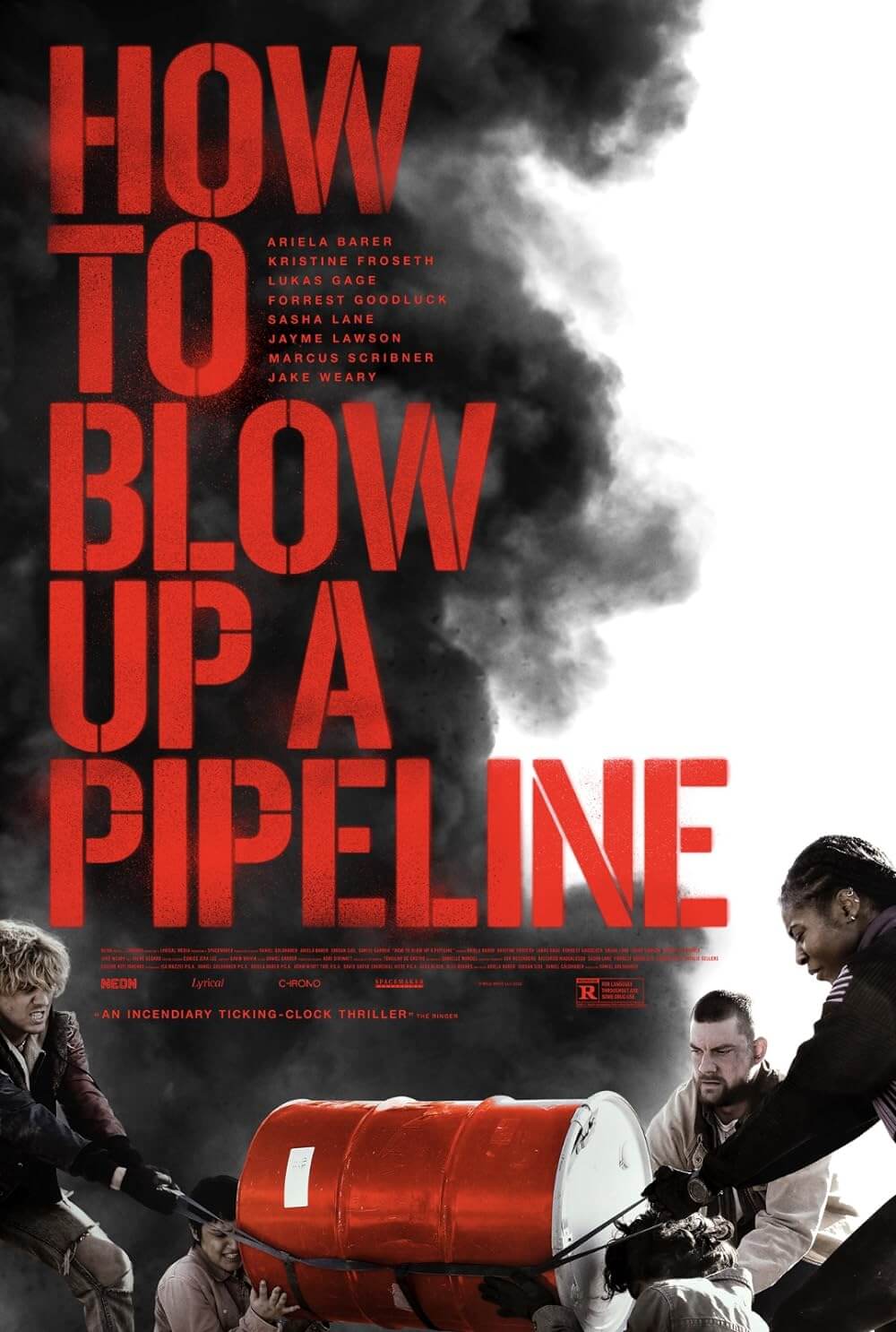

How to Blow Up a Pipeline

By Brian Eggert |

How to Blow Up a Pipeline will surely be divisive and, for some, an outright provocation. A tactile look at climate activism structured like a heist film, it concerns a generation fighting back against its bleak future, determined to “act outside of the system” and retaliate against the fossil fuel industry. The resulting eco-thriller is a propulsive and sharply considered experience from director Daniel Goldhaber, who, appropriately enough, treats the film like a group effort. In the press materials, Goldhaber shares credit along with co-writers Ariela Barer and Jordan Sjol, similar to the “Film by” credit shared with the writer of his first film, Cam (2018). With that collective spirit in mind, How to Blow Up a Pipeline follows a cadre of environmental activists who set out to commit an explosive act to disrupt oil prices. Distributed by Neon, the film walks the thin line between revolutionary advocacy and indie entertainment, offering an emblazoned marriage of the two. Fortunately, Goldhaber and his writers avoid didactic messaging thanks to the film’s relatable characters and kinetic situation. This is grounded filmmaking, superbly crafted and paced, that presents bold emotions and themes through an incendiary act of extremism.

The film is based on Swedish author and professor Andreas Malm’s nonfiction text, How to Blow Up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire. Published in 2021, Malm’s book outlines a history of sabotage and the destruction of property to achieve social, political, and institutional justice. Historically, sabotage has been used at the Boston Tea Party, to fight colonialism, and combat apartheid in South Africa. Though such acts were deemed terrorism then, they became ethical and strategic imperatives over time. In his critique of pacifism to combat the use of fossil fuels, Malm argues for the moral necessity of action. Whereas nonviolent activism does not dissuade investors from financially backing greenhouse gas emitters, Malm believes that sabotaging fossil fuel manufacturers or, say, luxury vehicles and yachts owned by the super-rich who support these systems, can produce results—if carried out in a manner that avoids harming people and animals or causing an ecological disaster. Moreover, given the threat of climate change to humanity, Malm believes that revolt against the fossil fuel infrastructure would not only work but is a moral choice toward a better ecological future.

Goldhaber and company take the ideas behind Malm’s book and develop a narrative around them. There have been plenty of movies about environmental sabotage and so-called eco-terrorists. But they often avoid taking the ideas of sabotage as activism seriously as strategic solutions. They also shrink from the topic by portraying their characters as morally compromised, emotionally disturbed, or deranged fanatics. And whatever moral questions they raise, the audience must answer. For instance, the extremist group in The East (2013) sets out to combat corporate corruption by taking action against the individuals responsible, putting people’s lives in danger. Can they be considered morally justified after harming people? Kelly Reichardt dealt with the human toll of sabotage in Night Moves (2013), suggesting a slippery slope that could lead to murder. Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2019) featured Ethan Hawke as a disturbed priest who takes action due to an existential and spiritual crisis. What makes How to Blow Up a Pipeline different is that Goldhaber attempts to understand the reasons and perspectives of his characters, who remain committed to their tactics, without the usual human flaw caveats that subtly imply this is the work of disturbed individuals.

Goldhaber and company take the ideas behind Malm’s book and develop a narrative around them. There have been plenty of movies about environmental sabotage and so-called eco-terrorists. But they often avoid taking the ideas of sabotage as activism seriously as strategic solutions. They also shrink from the topic by portraying their characters as morally compromised, emotionally disturbed, or deranged fanatics. And whatever moral questions they raise, the audience must answer. For instance, the extremist group in The East (2013) sets out to combat corporate corruption by taking action against the individuals responsible, putting people’s lives in danger. Can they be considered morally justified after harming people? Kelly Reichardt dealt with the human toll of sabotage in Night Moves (2013), suggesting a slippery slope that could lead to murder. Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2019) featured Ethan Hawke as a disturbed priest who takes action due to an existential and spiritual crisis. What makes How to Blow Up a Pipeline different is that Goldhaber attempts to understand the reasons and perspectives of his characters, who remain committed to their tactics, without the usual human flaw caveats that subtly imply this is the work of disturbed individuals.

Goldhaber’s film doesn’t build an argument like Malm’s manifesto, and neither the book nor the movie provides an actual instruction manual for blowing up a pipeline. Rather, Goldhaber immerses the viewer in the subjectivity of characters with clear-headed reasons and motivations behind their actions. The opening recalls the structure of Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama (2016), where brief scenes establish a group of characters, offering a glimpse of their lives before each follows a strict timeline, fulfilling a series of mysterious tasks and rendezvous. They assemble in the skeletal remains of a Texas house to prepare a workshop, hammer washers into flat metal bits, mix chemicals, craft electronic parts, and roll barrels full of explosives into position. What they’re planning and how they intend to achieve it remain unclear at first. Similar to the heist movie format of Ocean’s 11 (2000), the filmmakers do not reveal every detail, so the suspense comes from watching the plan unfold while knowing only the ultimate objective: their crew plans to detonate an oil pipeline in two spots, one underground and another above, the results of which will avoid any significant spillage.

Ratcheting the suspense with each notch of progress toward the activists’ ultimate goal, Goldhaber creates sympathy for his characters in chapters that shed light on their motivations. The de facto leader, Xochitl (Barer, also co-writer and producer), lost her mother, who lived near an oil refinery in Long Beach, California. Xochitl works with a pacifist group in Chicago, but their fliers and videos aren’t making progress. She wants to attack what’s destroying the planet. So she assembles a team: Shawn (Marcus Scribner) works closely with Xochitl and helps recruit others. The self-destructive Michael (Forrest Goodluck), a Native American from North Dakota whose land has been invaded by drillers, has taught himself to make bombs. Dwayne (Jake Weary), a Texas native whose home became a government eminent domain acquisition to build a pipeline, wants his land back. Xochitl’s friend Theo (Sasha Lane) has been diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia, known to appear in people who live near oil refineries, and Theo’s partner, Alisha (Jayme Lawson), is there to support her. The wild cards are Rowan (Kristine Froseth) and Logan (Lukas Gage), a horny couple who treat activism like the next high.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline isn’t a slick, polished movie. Shot on 16mm, it’s a scrappy production with a low budget—an operation not unlike the one onscreen: urgent, immediate, and a distinct contrast to the average studio project. Cinematographer Tehillah De Castro and editor Daniel Garber create a documentary-like aesthetic with handheld shots and stripped-down, unglamorous location photography in Los Angeles, North Dakota, and New Mexico. There are no big-name actors in the cast to dispel their authentic presence; instead, the production offers an unrelenting energy that reflects the situation and passionate perspectives of its characters. Gavin Brivik’s electronic music—somewhere between Vangelis and Elliot Goldenthal’s music in Heat (1995)—provides a galvanic undercurrent. Along with the glowing titles that transition every chapter, Brivik’s post-’80s synth music gives the proceedings a downright apocalyptic quality. Despite its grittiness and doom, Goldhaber and his co-writers deploy some effective heist movie tension and misdirections, making it impossible not to feel immersed in every moment and surprised by the outcome.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline isn’t a slick, polished movie. Shot on 16mm, it’s a scrappy production with a low budget—an operation not unlike the one onscreen: urgent, immediate, and a distinct contrast to the average studio project. Cinematographer Tehillah De Castro and editor Daniel Garber create a documentary-like aesthetic with handheld shots and stripped-down, unglamorous location photography in Los Angeles, North Dakota, and New Mexico. There are no big-name actors in the cast to dispel their authentic presence; instead, the production offers an unrelenting energy that reflects the situation and passionate perspectives of its characters. Gavin Brivik’s electronic music—somewhere between Vangelis and Elliot Goldenthal’s music in Heat (1995)—provides a galvanic undercurrent. Along with the glowing titles that transition every chapter, Brivik’s post-’80s synth music gives the proceedings a downright apocalyptic quality. Despite its grittiness and doom, Goldhaber and his co-writers deploy some effective heist movie tension and misdirections, making it impossible not to feel immersed in every moment and surprised by the outcome.

To be sure, there’s a sense of fatalism and self-sacrificial determination pushing the characters forward, each aware they will probably be labeled a terrorist by the authorities and media outlets. But as Michael declares, “If the American Empire calls us terrorists, then we’re doing something right.” Even though How to Blow Up a Pipeline explores what these characters are doing and why, it’s to understand them and create a visceral experience from their plan. The film never feels prescriptive; it doesn’t preach, even though it’s immersed in the characters’ perspectives and acknowledges the dangers of surviving on Earth for younger generations. Still, the choice seems clear when the options are to watch passively as these industries destroy the planet or to take action to create change. The film may soften the message by containing its ideology within a familiar, accessible scenario, but any other approach may feel like less impassioned storytelling. Regardless of how you may feel about the characters and their actions, the film is an exceptional thriller—fast-paced and burning with the fire of revolution.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review