Reader's Choice

House of Wax

By Brian Eggert |

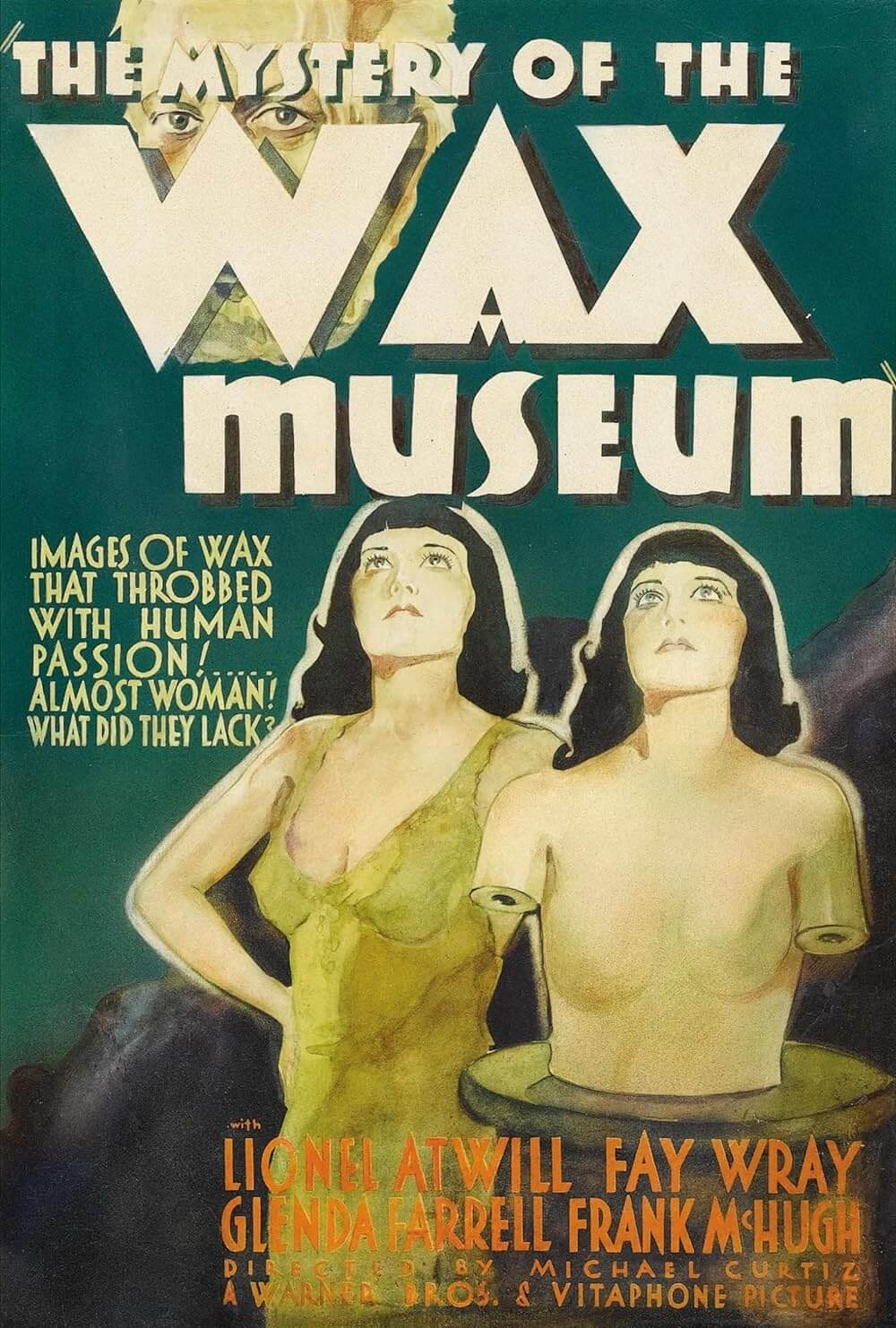

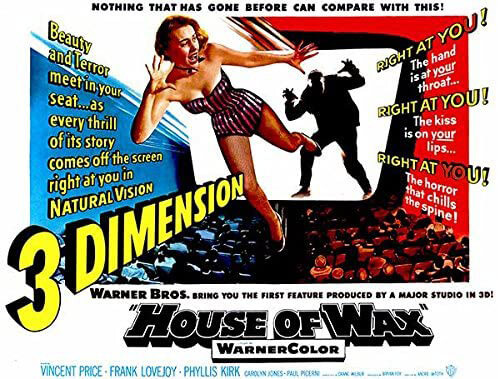

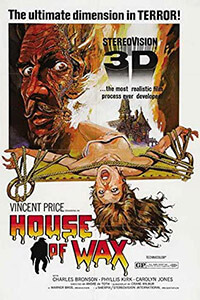

In the 1950s, monsters emerged from the shadows, and moviegoers had become accustomed to seeing them on the big screen. It was the Atomic Age, a period teeming with visitors from outer space and nuclear insects in titles ranging from The Thing from Another World (1951) to Them! (1954). At the same time, something like The Mystery of the Wax Museum, directed by Michael Curtiz for Warner Bros. in 1933 and shrouded in mood and shadow, would seem old-fashioned by the standards of 1950s audiences, who could find Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Wolf Man on late-night television broadcasts. People wanted to see their monsters; the more sensational, the better. Perhaps that’s why André De Toth’s remake, House of Wax from 1953, feels somewhat campy in comparison to Curtiz’s original. Although it was based on the same short story by Charles S. Belden, it was released in 3-D and stars Vincent Price under ghoulish makeup, captured in full color. Price’s mad sculptor scampers about on well-lit soundstages and has bright purple and pink scars over his face, lending the entire thing a sensational and somewhat comical tenor. If nothing else, it reinforces perceptions about the inferiority of remakes. Regardless of how charming Price may be as a cult novelty and how confident De Toth’s filmmaking seems, House of Wax feels like an unsubtle imitation designed to make a buck.

Indeed, the remake follows The Mystery of the Wax Museum so closely that it lacks any surprises. Aside from the initial setting of New York in the early 1900s, it uses many of the same story beats as Curtiz’s film. Price plays Henry Jarrod, a wax sculptor whose money-grubbing partner, Burke (Roy Roberts), sets his wax museum afire for the insurance money, burning all of Jarrod’s beloved creations, including his masterpiece of Marie Antoinette. Jarrod is believed dead, though not long afterward he appears garbed in black and his face deformed. Having turned himself into a phantom of the night, Jarrod murders Burke, only to later display the victim’s now-waxed corpse in his newly opened museum. In another disguise, Jarrod is wheelchair-bound and looks like his original self, but he remains unable to sculpt. Even so, he describes himself as “reincarnated” by the fire and uses assistants to complete his sculptures. When Sue Allen (Phyllis Kirk) recognizes her late friend Cathy (Carolyn Jones) in Jarrod’s sculpture of Joan of Arc, she tries to convince her boyfriend, Jarrod’s new apprentice Scott (Paul Picerni), that there’s something fishy happening in Jarrod’s House of Wax. Soon enough, Sue uncovers the truth, and the police, led by Lt. Tom Brennan (Frank Lovejoy), arrive just in time to prevent Sue from becoming Jarrod’s new Marie Antoinette.

House of Wax was one of the first pictures released by a major studio in the 3-D format. Throughout the 1950s, Hollywood devised a number of gimmicks to compete with the growing popularity of television. Some of them, such as color and widescreen photography, which had both debuted before television but were limited to “A” pictures only, would become the new standard over the next decade. But most of these techniques, many of them conceived by studio promotional departments, remain forgotten today. Perhaps that’s for the best, given their names: Smell-O-Vision, Illusion-o, and Hypno-Vista. Cinerama came the closest to succeeding, but the process, in which three separate projectors created an experience that surrounded moviegoers in a half-circle screen, proved too expensive to shoot and exhibit. None of them supplied any significant advancement in the cinematic medium; however, the possibilities of a three-dimensional viewing experience still fascinate Hollywood today.

House of Wax was one of the first pictures released by a major studio in the 3-D format. Throughout the 1950s, Hollywood devised a number of gimmicks to compete with the growing popularity of television. Some of them, such as color and widescreen photography, which had both debuted before television but were limited to “A” pictures only, would become the new standard over the next decade. But most of these techniques, many of them conceived by studio promotional departments, remain forgotten today. Perhaps that’s for the best, given their names: Smell-O-Vision, Illusion-o, and Hypno-Vista. Cinerama came the closest to succeeding, but the process, in which three separate projectors created an experience that surrounded moviegoers in a half-circle screen, proved too expensive to shoot and exhibit. None of them supplied any significant advancement in the cinematic medium; however, the possibilities of a three-dimensional viewing experience still fascinate Hollywood today.

Aside from a few experimental shorts and Bwana Devil—a B-movie distributed by United Artists in 1952 about killer lions (and based on real-life big cats, also the subject of The Ghost and the Darkness from 1996)—the 3-D format gave viewers a new kind of moviegoing experience that seemed to reach out from the screen. Warners used House of Wax as a testing ground for this and other new technologies, each branded with marketing spin. Onscreen credit is given to “Natural Vision 3-Dimension” shot in “Warnervision” color before Vincent Price’s name. And don’t forget about the four-track “WarnerPhonic” sound that rumbled theater seats. However hokey these gimmicks may seem today, Warners’ investment in newfangled exhibition technologies paid off on House of Wax, earning the studio over $20 million on the production’s $1 million budget. They also ensured that every other studio, even small-time hucksters like William Castle, would follow with promotions of their own. Working with Castle, Price became the king of movie gimmicks: he made several more titles in 3-D; he starred in House on Haunted Hill (1959), featuring the Emergo system where skeletons leaped at the audience; and he had the leading role in The Tingler (1959), which advertised Percepto!, a seat buzzer designed to give viewers a small jolt.

Still, watching House of Wax today takes some patience. Several scenes were inserted into the mix solely to enhance the theater-going experience and test the limits of 3-D. This is the downfall of most 3-D presentations screened later, at home, and on a traditional 2-D display (see the floating fish heads in Jaws 3-D or the yo-yo routine in Friday the 13th Part III). De Toth, despite having just one eye and being unable to see the full 3-D effect himself, oversaw the new process. Note the embossed opening titles, the compelling depth-of-field inside Jarrod’s museum, the objects that come flying at the camera, and even the poster’s tagline (“It comes off the screen right at you!”)—all typical of a 3-D production. The oddest 3-D scene must be the can-can dancers kicking their legs and presenting their bottoms to the viewer. But no scene brings the film to a screeching halt faster than the wax museum’s hype man, a barker armed with three paddle balls. In a sequence that seems to go on forever, he bounces rubber balls on a string and almost seems to break the fourth wall (“Lookit that, a bag of popcorn”). The extended sequence finally ends when an onlooker faints after the barker catches the three balls in his mouth.

Audiences in 1953 may have caught The Mystery of the Wax Museum on television; otherwise, they had twenty years to forget about the similarities between the original and its remake. Explorers of film history today aren’t so lucky. Watching the two films in sequence within a few days, months, or even a year or two apart, one cannot ignore how much House of Wax resembles its predecessor. Then again, over the years, House of Wax has become the more popular film given the cult around Price’s celebrity and the camp quality of his performances during this period. Doubtless, most of today’s viewers will see House of Wax before its predecessor, which may mute the effect of the 1933 film. Although screenwriter Crane Wilbur made small alterations to the setting and characters, the story’s general structure remains intact between the two films. De Toth and his set decorator Lyle B. Reifsnider all but reconstruct the mad sculptor’s lab from the design of the original set as well, while the director repeats a memorable shot of a human hiding among several wax heads. One gets the sense that De Toth sought to pay homage to Curtiz with small flourishes, such as a scene where the camera follows a large shadow creeping along a wall—a Curtiz visual signature. And when Price says, “People say they can see my Marie Antoinette breathe, that her breast rises and falls,” it is perhaps a wink to the camera catching Fay Wray breathing as the statue in the original.

But House of Wax lacks the atmosphere and provocative touches of the Pre-Code original; it’s also less progressive. Given the enforcement of the Production Code in 1953, the moral standards of the day meant that certain references from the original had to be omitted for the remake. For instance, The Mystery of the Wax Museum’s allusions to sexuality have been removed. The sculptor’s heroin-addicted minion becomes a more palatable alcoholic in the remake. And, predictably, the police stop Jarrod in the remake, whereas they were mostly ineffectual in the original, leaving the final battle up to the boyfriend. By the end of House of Wax, the audience’s faith in systems of authority and order in the universe have been restored. What is more, The Mystery of the Wax Museum followed a strong-willed, no-nonsense female reporter played by Glenda Farrell; there’s no such character in the remake, just Sue. It’s a thankless role for Kirk, playing a typical horror movie damsel. Besides her inability to scream as well as Fay Wray, her character is reduced to doubting herself among men who refuse to believe her worst fears about Jarrod’s sculptures.

But House of Wax lacks the atmosphere and provocative touches of the Pre-Code original; it’s also less progressive. Given the enforcement of the Production Code in 1953, the moral standards of the day meant that certain references from the original had to be omitted for the remake. For instance, The Mystery of the Wax Museum’s allusions to sexuality have been removed. The sculptor’s heroin-addicted minion becomes a more palatable alcoholic in the remake. And, predictably, the police stop Jarrod in the remake, whereas they were mostly ineffectual in the original, leaving the final battle up to the boyfriend. By the end of House of Wax, the audience’s faith in systems of authority and order in the universe have been restored. What is more, The Mystery of the Wax Museum followed a strong-willed, no-nonsense female reporter played by Glenda Farrell; there’s no such character in the remake, just Sue. It’s a thankless role for Kirk, playing a typical horror movie damsel. Besides her inability to scream as well as Fay Wray, her character is reduced to doubting herself among men who refuse to believe her worst fears about Jarrod’s sculptures.

House of Wax is best when it delights in the macabre, more exploitative aspects of its story. The scenes with Price are especially juicy, as he speaks with typical grandiosity about the historical background of his wax subjects and “morbidly curious” tastes of his museum patrons, thus, the film’s audience. Before his encounter with the fire, Jarrod refuses to satiate his patrons’ desire for a “chamber of horrors,” but afterwards, he delights in showing crimes of violence in wax (a stabbing, an assassination, and executions: the guillotine, the electric chair, the rack). And just as in The Mystery of the Wax Museum, his sculptures’ melting faces in the fire sequence are genuinely unnerving. The remake also benefits from Igor, played by a creepy Charles Buchinsky (later known as Charles Bronson). Originally, Igor was the name of the sculptor, though it was almost certainly changed once the horror genre began associating the name “Igor” with assistant roles. Less scary are the scenes of Jarrod lurking about in his black coat and hat, haunting Sue at night. De Toth shoots these scenes with the fog machine on high and the shadows to a minimum. Although, Price’s appearance in these scenes, not to mention his character’s ability to construct a false face, seems to have inspired Sam Raimi’s antihero in Darkman (1990).

The idea behind House of Wax, where a sculptor molds sculptures out of corpses by sealing their bodies in melted wax, remains inherently disturbing. To be sure, the most alarming thing about the film may be that it unconsciously inspired artist Gunther von Hagens, whose plastination process preserves anatomical wonders for his fascinating Body Worlds exhibition. Nevertheless, the requirements of a 3-D exhibition rob the film of the original’s mystery and atmosphere today. This is curious, since its older setting in the early 1900s, complete with turn-of-the-century costumes and foggy cobblestone streets, lend themselves to rich Gothic storytelling. But House of Wax prefers to forego any eeriness for silly devices and cheap tricks to sell its scares, which prevent the viewer from fully immersing themselves in the storytelling. Though one can imagine the experience being a lark in 1953, accompanied by a crowd of teenagers watching with equal measures of chills and irony, the experience remains a historical curiosity—like one of the sculptures in Jarrod’s museum, little more than a convincing copy of the real thing.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Hefferman, Kevin. Ghouls, Gimmicks, and Gold: Horror Films and the American Movie Business. Duke University Press, 2004.

Lev, Peter. Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959. University of California Press, 2006.

Paszylk, Bartłomiej. The Pleasure and Pain of Cult Horror Films: An Historical Survey. McFarland, 2009.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review