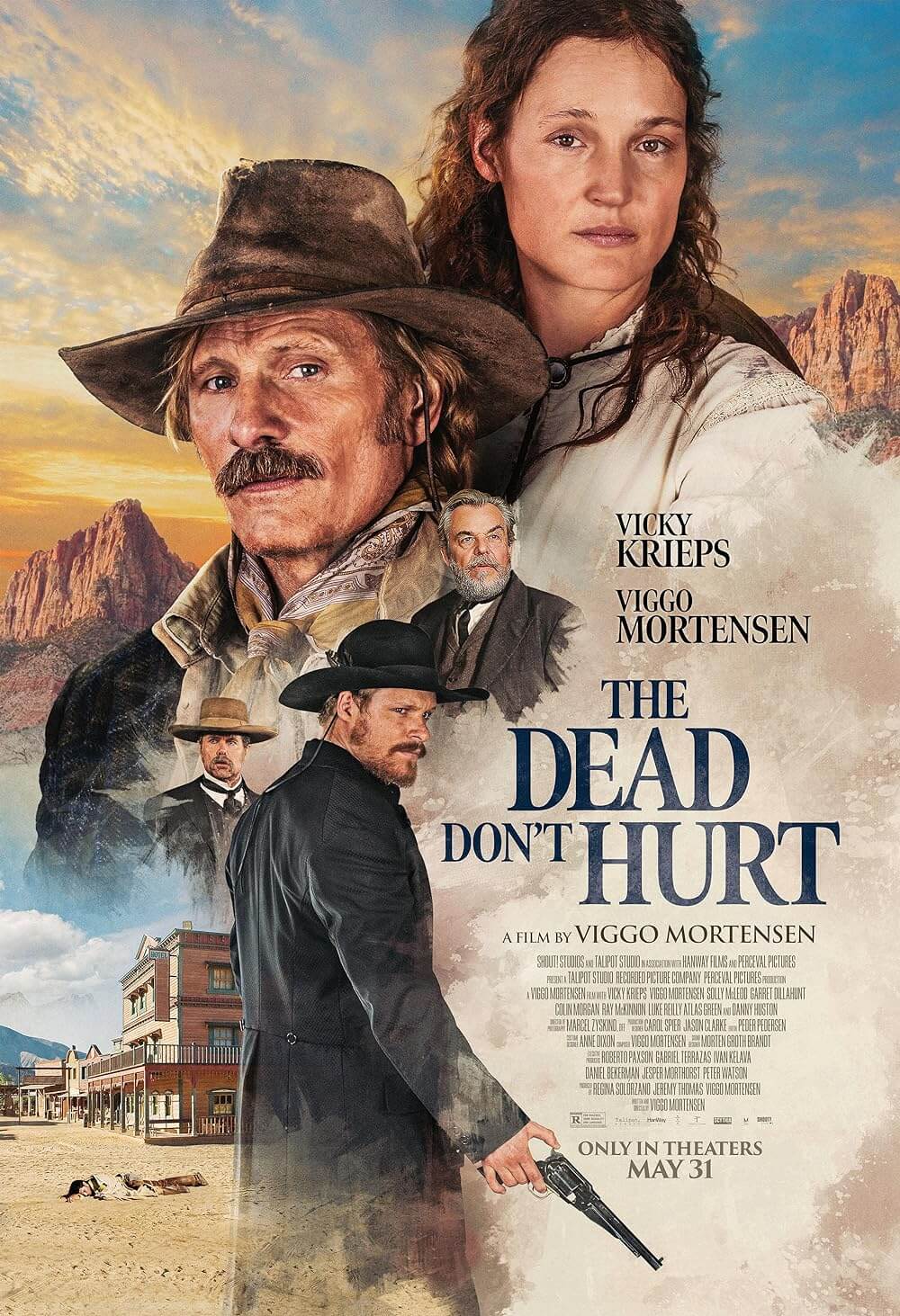

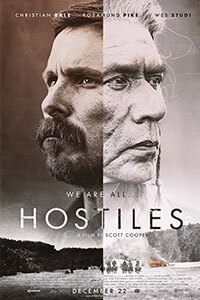

Hostiles

By Brian Eggert |

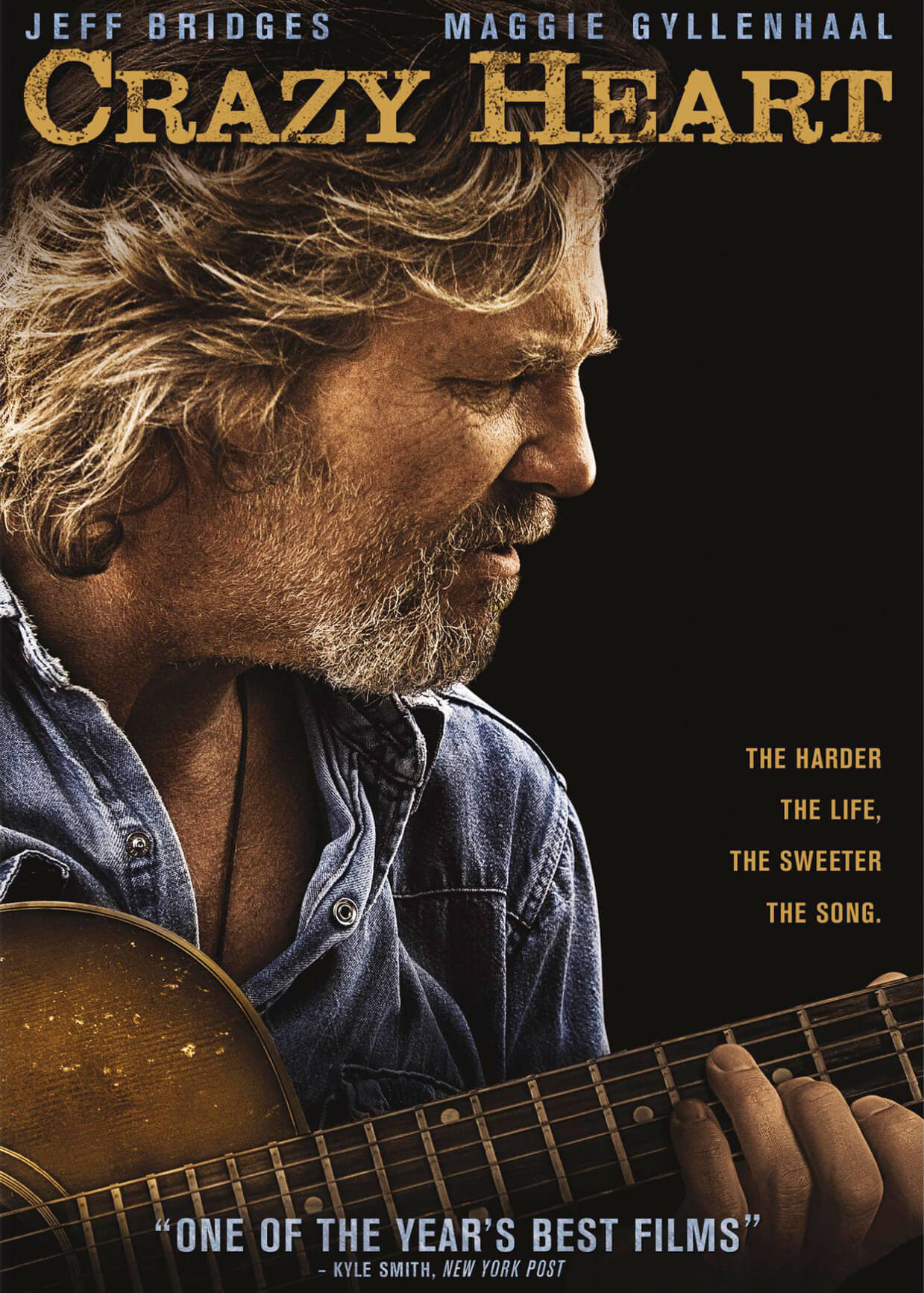

In Hostiles, writer-director Scott Cooper (Crazy Heart, Out of the Furnace, Black Mass) uses a Western landscape to explore historical accountability and deconstruct moral certainty in the United States. His film opens with the famous D.H. Lawrence quote: “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.” Although the average citizen of the United States today has been sated by capitalism, Lawerence’s words were never truer than their application to the American West. Cooper’s largely white characters have survived Civil War and the so-called Indian Wars in which white colonists obliterated native tribes; they are killers and survivors. But in 1892, the year the film takes place, there are no major conflicts. The characters must reflect on their past violence and try to avoid committing new atrocities, all while hoping for redemption. Beautifully shot and acted, Hostiles is an impressive production that explores notions of identity, history, and humanity. Even so, the film’s lofty thematic ambitions are occasionally thwarted by its limited characterizations and white perspective.

Cooper adapted his script from an unpublished manuscript by Donald E. Stewart, writer of the Costa-Govras picture Missing (1982). The material feels inspired by the career of John Ford, specifically Ford’s later titles that began to question the classical Western dichotomies of cowboys and cavalrymen as heroes against the savage Indian. Early in his career, Ford helped define the archetypes of the Western genre with The Iron Horse (1924) and Stagecoach (1939). Later on, he seemed to question and rethink those oppositional conflicts, bringing an added dimension to Western mythology. With The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), he questioned the notion of history when his film coined the phrase, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Two years later, he released Cheyenne Autumn, a film with an almost funerary tone as it follows a massive party of Cheyenne from their barren Oklahoma reservation to their ancestral home in Wyoming. Despite the potential sympathy of such a story, it’s told from the perspective of Richard Widmark’s cavalry officer who questions his orders when he’s tasked with stopping the Cheyenne from returning home.

Hostiles reminded me of both Cheyenne Autumn and Ford’s The Searchers (1956)—a film that presents John Wayne as a problematic hero because his racism against Comanches has left him wounded, warped, and bent on revenge. Nevertheless, The Searchers portrays its Comanche characters as savages who kill indiscriminately. Similarly, Cheyenne Autumn exuded white guilt over the forced relocation of peoples who were slaughtered and whose land was stolen. But Ford never quite reached the point where his guilt resulted in giving his Native American characters agency in their representation. They inhabited those all-too-familiar tropes of the stoic noble or the inhuman savage. Cooper, though he means well with his on-the-nose title and carefully constructed narrative structure, does not transcend those narrow representational limits for Native Americans.

The severity of Cooper’s treatment is apparent from the first sequence. Rosalee Quaid (Rosamund Pike) loses her three children and husband to Comanche raiders. It is a vicious, violent act of one group encroaching on the land of another, a setup he returns to late in the film. Rosalee’s subsequent trauma results in her terror at the sight of any Native American. Captain Joseph Blocker (Christian Bale) bears a similar prejudice, having fought in the Indian Wars, where he endured, and caused, atrocities against an enemy he still hates. Blocker and Rosalee’s prejudices against Native Americans are tested when he receives orders, passed down from the President, to transport a group of Cheyenne prisoners from New Mexico to their ancestral home in Montana. Most of the Cheyenne characters (including Adam Beach and Q’orianka Kilcher) occupy the noble savage trope, especially their leader, Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi). Blocker is accompanied by his longtime friend, Master Sergeant Thomas Metz (Rory Cochrane, excellent), who suffers from melancholia, and several supporting players.

The film cannot help but feel episodic, as Blocker and his party encounter a series of unfriendlies on the trail to Montana. Early on, the Comanches who killed Rosalee’s family attack, and Yellow Hawk wants to retaliate. The group brushes with a pair of white fur trappers who kidnap and rape some of the women under Blocker’s care. After stopping at a fort for supplies, Blocker’s mission is complicated when he’s asked to escort a cruel murderer of Native Americans (Ben Foster) to prison. Each chapter seems to balance the other; for every horrible Native American act committed early in the film, there are even crueler and petty white men to follow. In a corny touch, and in gross defiance of its cynicism and bloody violence, love solves everything in the end. However inauthentic such an ending may be after enduring more than two hours of bitter, unflinching human savagery, it’s also a wonderfully handled moment.

An impressive, independently financed production, Cooper’s $40 million picture will not strike a chord with mainstream audiences. Though in time, Western enthusiasts may come to regard it as one of the few serious-minded entries in the genre of the 2010s. Cooper has drawn heavily from Fordian motifs, as suggested, and his visual sense evokes Terrence Malick in his use of morning light and sun-drenched clouds. In one impressionist sequence—where Bale wanders in a field, buries his hands in the dirt, and looks for answers in the landscape—Cooper uses abrupt cuts that belong to Malick’s recent style (see Bale in Knight of Cups). Aside from this misplaced scene, Cooper’s treatment is measured and elegant. The revisionist quality of his film recalls Heaven’s Gate (1980) and Unforgiven (1992) in its use of spare scenery, natural light, and shadow. The pristine lensing by cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi adheres to an earthy palette of colors, captured while filming on location in New Mexico and Arizona.

The performances echo the equally harsh and serene landscape. Pike once again demonstrates that her talent far exceeds her usual roles; she’s brilliant here in her scenes of emotional ruin, followed by the gradual hardening of her character. Bale, behind a thick mustache and perpetual frown, seems to carry the weight of the United States’ crimes against the Native Americans. Studi, Beach, and Kilcher, while representing a whos who of Native American performers, inhabit one-note roles dependent on unfortunate stereotypes. Elsewhere, Cooper’s supporting cast is comprised of a dream roster of character actors: Jesse Plemons, Timothée Chalamet (underused), Stephen Lang, Peter Mullan, and Bill Camp make up the ranks. Jonathan Majors plays Blocker’s longtime friend, Buffalo Soldier Henry Woodson, and represents the sole person of color in the cast. His inclusion, while well-acted, seems like a device to establish that Blocker isn’t a complete bigot—his prejudice is just situational, a theme reinforced by the mutual respect that forms between Blocker and Yellow Hawk.

The performances echo the equally harsh and serene landscape. Pike once again demonstrates that her talent far exceeds her usual roles; she’s brilliant here in her scenes of emotional ruin, followed by the gradual hardening of her character. Bale, behind a thick mustache and perpetual frown, seems to carry the weight of the United States’ crimes against the Native Americans. Studi, Beach, and Kilcher, while representing a whos who of Native American performers, inhabit one-note roles dependent on unfortunate stereotypes. Elsewhere, Cooper’s supporting cast is comprised of a dream roster of character actors: Jesse Plemons, Timothée Chalamet (underused), Stephen Lang, Peter Mullan, and Bill Camp make up the ranks. Jonathan Majors plays Blocker’s longtime friend, Buffalo Soldier Henry Woodson, and represents the sole person of color in the cast. His inclusion, while well-acted, seems like a device to establish that Blocker isn’t a complete bigot—his prejudice is just situational, a theme reinforced by the mutual respect that forms between Blocker and Yellow Hawk.

Cooper’s film both embraces and questions the mythology of the West. He underscores the violent past of the United States and yearns for atonement, but then he also relies on many of the same generalizations he tries to dispel. Whether he does this knowingly as a commentary on the capacity for white Americans to casually live with their past crimes, or by oversight, depends on the viewer’s interpretation. But it should be noted how much of Hostiles plays out as quite obvious, making it unlikely that Cooper’s simplistic message would be lost. As the tagline (“We are all…”) and title (Hostiles) suggest, the film boasts a didactic quality that reinterprets Western mythology and portrays both sides of the classic Cowboy vs. Indian conflict as capable of atrocity. Nevertheless, the film comes from a white perspective and gives personality to its white characters exclusively, making it politically troubling. The material effectively implants a sense of remorse, but at the cost of another revisionist Western that makes the same mistakes all over again. Still, Cooper’s film is gorgeous and his cast superb. Though Hostiles doesn’t rewrite the genre, it represents a thought-provoking contribution.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review