Hollow Man

By Brian Eggert |

Invisible men usually become irrational and power-hungry madmen in science fiction. This has been true since H.G. Wells first published The Invisible Man in 1897 and set his titular scientist loose on a transparent reign of terror across the English countryside. Wells’ excellent text has the good fortune of being imaginative, ahead of its time, and unavoidably naïve in matters of science, speculative or otherwise. But there’s no excuse for Hollow Man, Paul Verhoeven’s hokey and ill-received VFX letdown from 2000, which had more than 100 years to elaborate on Wells’ story and develop the psychology of its invisible man. After several science-fiction blockbusters—RoboCop (1987), Total Recall (1990), and Starship Troopers (1997)—each layered in extreme violence and surprising intellect, the Dutch filmmaker returned to the genre for this underwhelming and needlessly gory experience that, unlike his other forays into bloody sci-fi, contains none of the brains or thoughtful dimensions that audiences have come to expect from Verhoeven’s visceral-yet-witty brand of cinema.

The screenplay by Andrew W. Marlowe, writer of Air Force One (1997) and End of Days (1999), pays homage to Wells by following a similar structure to The Invisible Man, in which an egomaniacal scientist makes himself invisible and, because he no longer has to look himself in the mirror, becomes a madman killer. And aside from a few intriguing innovations in how the invisible man himself is represented onscreen, Marlowe doesn’t deviate from this very basic blueprint. Granted, no credit to Wells is given or warranted due to the vast restructuring of the scenario, but the influence is apparent. Hollow Man surrounds a top-secret research program funded by the Pentagon to create invisible soldiers. Still in the development stages, the project is headed by resident genius Sebastian Caine (Kevin Bacon), who, along with his group of scientists from various fields, toils in a spiffy underground lab. Their efforts have effectively rendered a few animals invisible, but they have yet to perfect the process. An early scene shows Caine finally cracking some unintelligible formula we don’t understand beyond the word “UNSTABLE” changing to “STABLE,” inciting Caine to advance his team’s testing onto humans.

Humans are exactly what Hollow Man is missing—interesting ones anyway. Caine is an absurd character, a “bad boy” scientist and narcissist who drives a sports car, wears a black leather jacket, and gazes out his window at a woman across the way. When he’s not peeping or feeding his god complex (the title’s “hollow” has a double meaning), he’s harassing his staff, among them his ex-girlfriend Linda (Elisabeth Shue) and her new boyfriend (Josh Brolin). Shue and Brolin are two credible stars who haven’t been given compelling characters to develop here; their roles are bland, despite being the heroes of the movie. Among the other characters are specialists played by Kim Dickens, Greg Grunberg, Joey Slotnick, and Mary Randle—all of them present to increase the body count later on, when things get messy after Caine loses it post-invisibility. Indeed, Caine insists on being their first human subject, and, predictably, his eventual invisible status has mental consequences, amplifying Caine’s personality disorders. His obsession with Linda becomes unchecked jealousy, his voyeurism turns into rape in a creepy subplot, and his intellectual resentment of his staff turns into pure violence. Halfway through the film, the science fiction becomes secondary to a jarring series of slasher-movie and cat-and-mouse clichés. (The movie’s corny tagline: “Think you’re alone? Think again.”)

The science of Hollow Man is shaky at best and fails to answer some very basic questions about invisibility that one cannot fault Wells for never asking, and which Hollywood has never bothered asking since. For example, how does a person see when turned invisible? After all, to see our eyes require light to reach our retinas; but if the retinas are invisible, then the brain cannot receive information about what we’re supposed to observe. In effect, an invisible person should be blind. Of course, what kind of invisible man thriller would it be if the main character struggled with blindness for two hours? As for how the scientists achieve invisibility, the film is no more thoughtful about its science than Wells’ chemical potions. Here, their process is called a “quantum phase shift,” suggesting that Caine will be vibrating at a different rate than normal matter, and therefore light will pass through him—a neat concept injected with just enough pseudo-scientific technobabble to sound plausible to John Q Moviegoer. We see Caine injected with a blue serum, and gradually, layers of skin, muscle, organs, and lastly, bone disappear, leaving only a seemingly empty bed sheet rising and falling with Caine’s breath.

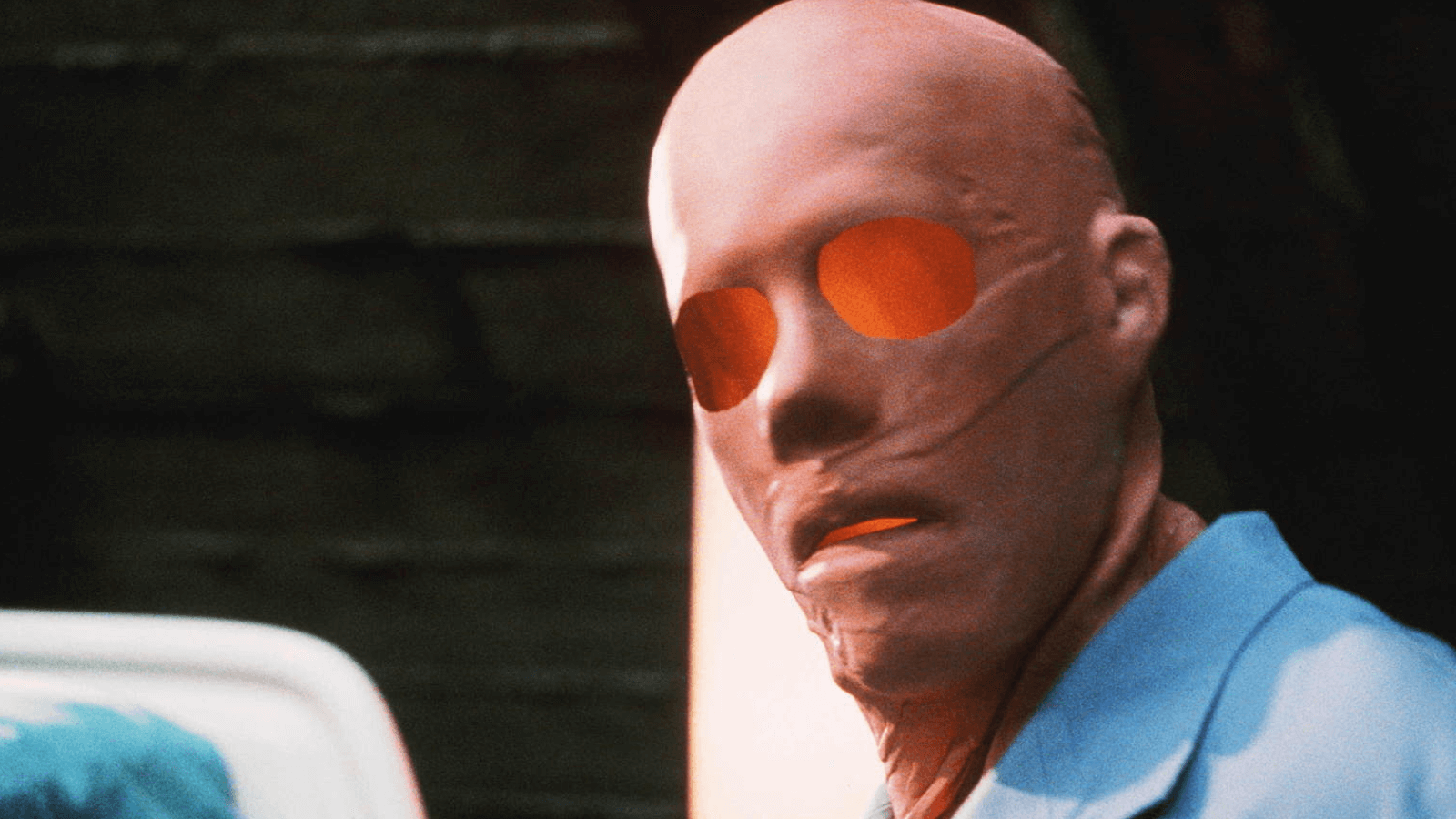

Oscar-nominated effects bring the invisibility process to remarkable life, whereas Bacon’s transparent appearance takes various shapes throughout Hollow Man. He’s seen in infrared goggles during Predator-like point-of-view shots; moving objects such as swinging doors alert us to his presence; the outline of his bare body is defined by water or, in a grotesque scene, bags of blood tossed into the air. For much of the movie, Bacon acts through a flesh-colored latex mask with empty holes where his eyes and mouth should be. These images alone were worth the price of admission in 2000 and warrant a revisit today, but none of the invisibility concepts or CGI are groundbreakingly original. James Whale was moving doors and lifting books with strings back in 1933 with his wonderful adaptation of Wells’ book for Universal Pictures, starring Claude Rains. And John Carpenter first tested the “invisibility CGI” waters back in 1992 on Memoirs of an Invisible Man, an underrated comedy-thriller starring Chevy Chase and Sam Neil.

Set aside Hollow Man’s striking visuals and the remainder is an assemblage of tedious characters, mindless plot developments, and recycled elements from better movies—none of which contain Verhoeven’s distinctive touch. The director’s wry sense of humor and self-aware smarts, evident in his other sci-fi fare, revert into what might be called his “Showgirls mode”—supplying an audience with the basest of moviegoing needs. However effectively realized on a technical level and only mildly watchable, primitive thrills are the movie’s lowbrow objectives, as Marlowe’s screenplay avoids any in-depth discussion of Caine’s psychological breakdown or the endless possibilities inherent to becoming invisible (apparently, Marlowe hasn’t read Plato’s second book in Republic). Instead, the movie uses invisibility as the novelty by which a routine series of events unfold. That the story involves an invisible man at all seems like an inconsequential detail once the screenplay’s slasher autopilot is engaged. And though the underdeveloped narrative and scientific concept remain frustrating, the biggest disappointment about Hollow Man is that it bears Verhoeven’s name but that his presence is almost invisible.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review