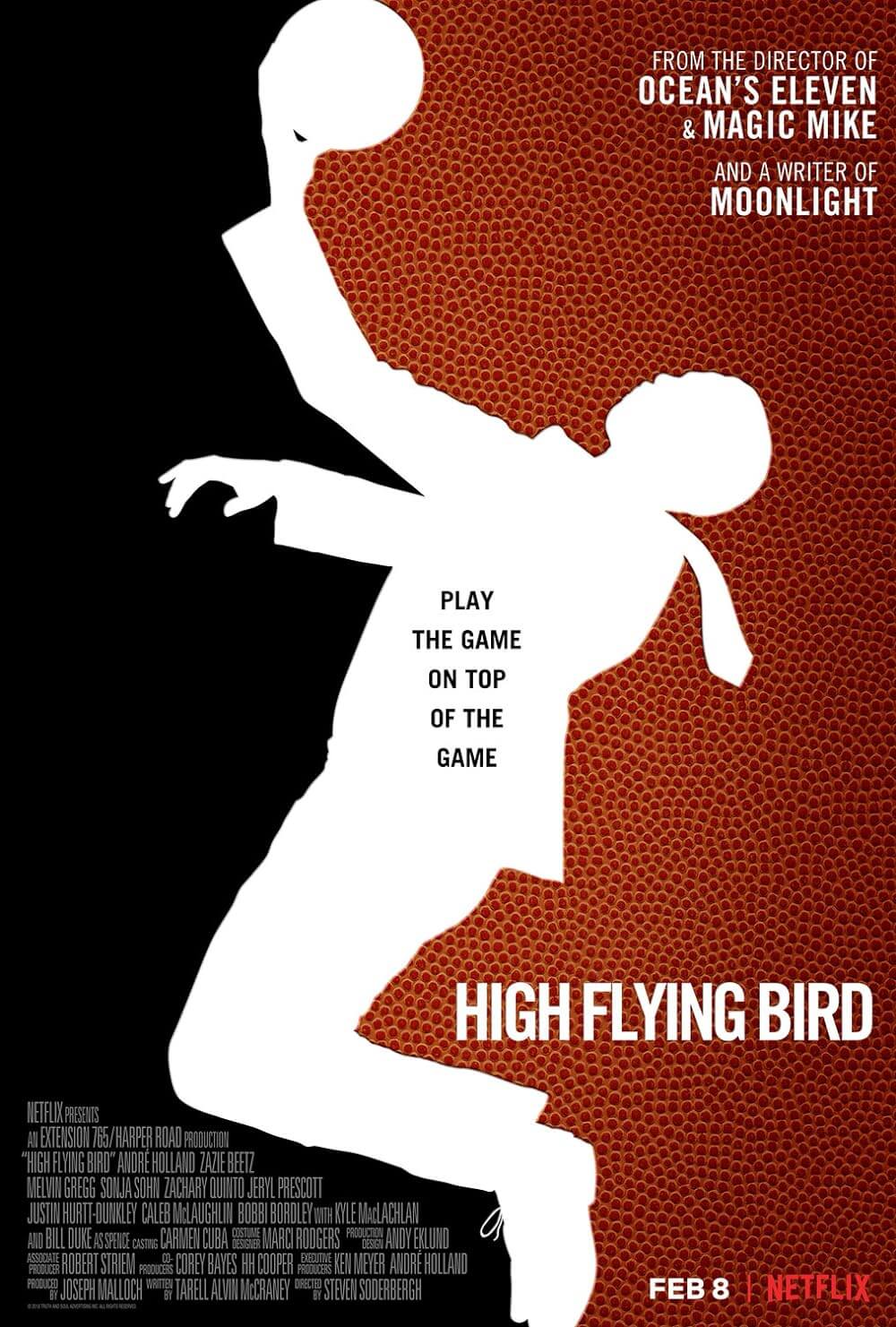

High Flying Bird

By Brian Eggert |

In High Flying Bird, André Holland plays a sports agent named Ray Burke who finds himself in a unique situation. The NBA has enacted another lockout, halting player salaries to negotiate a new labor deal with the team owners and television networks. The flow of money has frozen, and Ray’s star client, Erick Scott (Melvin Gregg), a number one draft pick who’s waiting to launch a career as a superstar, is getting anxious. Ray is anxious too. At a lunch meeting with Erick, the restaurant declines his agency’s expense card. Now Ray walks from one meeting to another in the opening scenes, deescalating one situation and trying to control the next one. As he does, director Steven Soderbergh captures Ray crossing the street, and behind him, an armored car waits at a stoplight. The brief image suggests that High Flying Bird is like an elaborate heist movie, where Ray must determine how to break inside a well-protected moving target that has all the money his client will ever need.

Although the film is about basketball, it’s less about the sport and more about the business and its effect on people’s lives. It has that in common with Steve James’ Hoop Dreams (1994) and Spike Lee’s He Got Game (1998), clear sources of inspiration for its playwright-turned-screenwriter Tarell Alvin McCraney. Along with Barry Jenkins, McCraney won an Oscar for Moonlight (2016), an he’s authored several Broadway hits. But McCraney’s style in High Flying Bird cuts into its subject matter with a razor’s edge. His writing recalls that of David Mamet, with a fast volley of crackerjack dialogue, negotiation, and insults exchanged between the smartest people in every room they enter. Also similar to Mamet, McCraney’s story—and perhaps this is a spoiler—is a con game with a master grifter and deal-maker at the center. Quite simply, more than the cast or even Soderbergh’s direction, McCraney’s writing is the star of the show.

With nothing more than a few dollar bills in his wallet, Ray bounces between a series of meetings that signal impending disaster, yet he’s suspiciously calm. He must contend with his boss (Zachary Quinto), who announces that the agency will be moving into a more stable, lockout-free market of hockey. His soon-to-be-former assistant Samantha (Zazie Beetz), who idolizes Ray, nonetheless realizes she must outmaneuver him if she wants to become him. An agent for the player’s association, Myra (Sonja Sohn), and the sleazy owner of the New York team (Kyle MacLachlan), also scheme and cut deals to ensure their own futures. Holland is supremely charismatic in these scenes, having worked with Soderbergh on Cinemax’s short-lived series The Knick (2014-2015). All the while, there’s talk of the philosophy of the game on the court, the difference between the official “organized” corporate game run by rich white men, and by contrast, the more vital street ball dominated by players of color.

In another strain of the film, Ray exposes how the NBA “invented a game on top of the game” after 1950 by inviting African American players into their league, and then turning that league into an exploitative business that more than one character compares to slavery. Ray’s former coach and mentor, Spence (Bill Duke), runs a youth basketball program, and he resents comparisons between basketball and slavery. When someone makes such an analogy in his presence, he requires them to recite the same prayer: “I love the Lord and all his black people.” But Ray has figured out how to get players like Erick paid by circumventing the NBA during the “sweet spot” of the lockout. He equates the action to a slave revolt or, more accurately, the rhetoric of Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton’s belief that black workers must unite: “All members of the working classes must seize the means of production […] to do this we must become psychologically free so that we can be fully capable of meaningful self-determination.”

Soderbergh, working under his usual pseudonyms—Peter Andrews as cinematographer and Mary Ann Bernard as editor—once again experiments with an iPhone. Frankly, his work on last year’s thriller Unsane delivered a better use case for the medium. Here, the wide-angle lensing and smooth extended shots allow for maximum mobility, whereas the film’s many smaller, intimate scenes suffer. His standard two-shot conversations, for instance, quickly become repetitive, as do the many shots of Ray walking around New York City. At other times, the film looks so good that it’s impossible to believe it was shot using a mobile device. Consider the elegance of several monochrome inserts, which serve almost like thematic introductions delivered by three real-life professional players (Reggie Jackson, Donovan Mitchell, and Karl-Anthony Towns). At the same time, the screenplay integrates story elements about smartphones and streaming services, as though McCraney somehow knew that Soderbergh would shoot the film this way, and it would eventually be released by Netflix.

High Flying Bird tackles issues of race, exploitation, and image in the sports entertainment industry. Its issue-heavy substance is rendered light-as-a-feather by McCraney’s writing, however, and the con game driving the plot is nothing short of thrilling. Following Ray, he executes one blow after another in a corporate sparring match that’s like boxing “but without the brain damage.” But it’s not all gamesmanship and negotiation. Throughout, there’s a persistent theme that players must “always be on the clock” to maintain their reputation—which underscores the film’s themes of slavery and begs the question: Why aren’t they being paid during the lockout? At a brisk 90 minutes, Soderbergh and McCraney offer a smart, thoughtful investigation into grandiose themes with copious amounts of verbal showboating, but it’s handled with such intimacy among its characters and energy in its momentum that it never feels preachy or didactic, just urgent.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review