Heretic

By Brian Eggert |

A passionate debate about belief systems and religious history can be healthy and productive. It can also be dangerous, depending on the motivations of those involved. In Heretic, two young Mormon missionaries visit a Colorado home and get drawn into a discussion about why they believe what they believe. Are they making assumptions based on what they’ve seen or been told? Do they believe based on blind faith or just because it makes them feel good? That conversation becomes a frightening intellectual and physical trap in the latest from writer-directors Scott Beck and Byran Woods. The duo also made a nasty little slasher, Haunt (2019), about killers operating an out-of-the-way extreme haunted house. And here’s another film about a predator luring unsuspected victims into a familiar situation, only to reveal they’ve been caught in a particularly warped snare. Heretic, far more cerebral, cinematic, and dialogue-driven than the filmmakers’ other work—including the entertaining B-movie 65 (2023)—is their most accomplished feature to date and 2024’s best horror film.

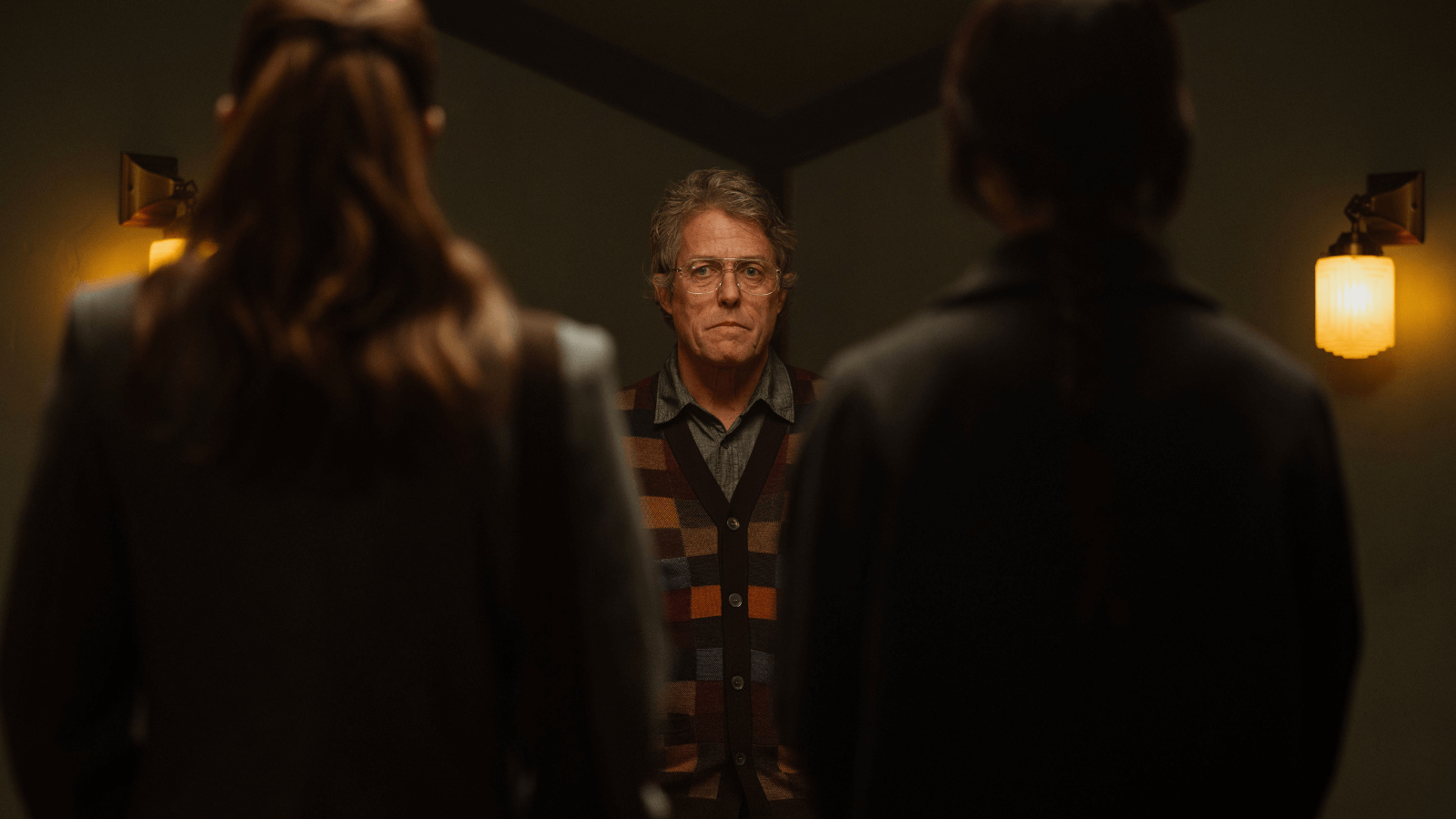

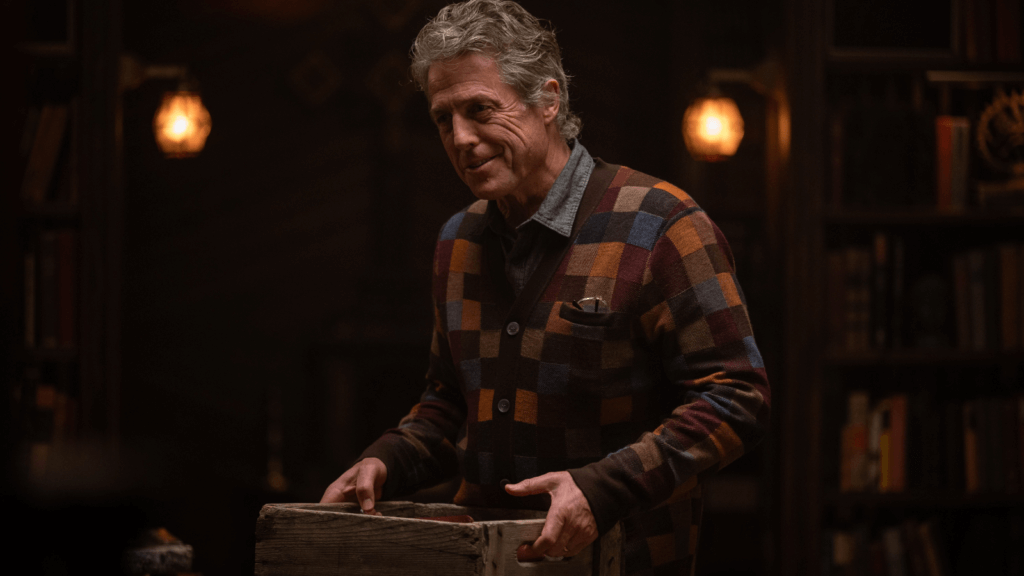

Spreading the word for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Sister Paxton (Chloe East) and Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) knock on doors, hoping to tally a few converts. With the weather getting ever more treacherous, they visit the unassuming Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant), whose bookish appearance and general chumminess prove so welcoming that they step inside his house for a slice of blueberry pie. Reed says his wife is baking in the other room, and the presence of another woman means they can enter. But once they begin peddling their religion, he asks questions about their beliefs, poking holes in their ideas—never in a smug way, mind you. He keeps the tone friendly and conversational yet confronts them about polygamy. Before long, he convinces them to move from the living room to his library, which they do, even while their internal alarms tell them something isn’t right. Maybe it’s that his wife never appears, or the candle on the coffee table burns with a blueberry pie scent, but this man isn’t what he seems. Sure enough, Mr. Reed lives in an intricately built home designed to catch and keep people. But for what purpose? Once they’re inside his library, he proceeds not with a horror show but with a lecture.

Using pop music and board games to show how one iteration borrows from the last, Reed waxes about allusionism and influence in religion. For instance, he notes how The Hollies’ “The Air That I Breathe” inspired Radiohead’s “Creep,” which then inspired Lana Del Rey’s “Get Free,” with each version prompting a lawsuit due to their similarities. That’s comparable to the way religion has evolved, Mr. Reed says. Notice how many ancient Mesopotamian religions had imagery and mythology that found their way into Christianity. Several ancient deities were born on December 25 to a virgin mother, walked on water, and healed the sick. Those who devised the Christ myth undoubtedly drew from those earlier narratives. Doesn’t this implant some serious doubt about the authenticity of events and beliefs in the religious texts that have led to Judaism, which informed Christianity and, in turn, led to Islam? Each set of beliefs and texts builds upon the last, with traceable allusions to earlier versions. Sister Barnes would rather focus on the differences between these religions to dispel the comparisons, but Mr. Reed cannot help but see a pattern among them.

Just as the skeptics and atheists in the audience begin to nod in agreement and think Mr. Reed isn’t wrong, his behavior becomes more insidious and his plan more warped, speaking of “one true religion” and gradually revealing his demented agenda. Still, for much of Mr. Reed’s dialogue-heavy lecture, Grant is devilishly charming, using humor and sound logic to mask a looming sense of danger. Thatcher and East, who were both raised as Mormons, show an almost naive surface at first, disguising their mounting yet contained terror. The effect recalls Speak No Evil (2022, 2024) in its maddeningly polite characters who, initially anyway, dismiss warning signs of possible impending danger because to do otherwise would be rude. Reed preys on their conditioning as Mormon women to behave with humility and modesty, leading them down an elaborately arranged path to nightmarish revelations in his basement and sub-basement. Beck and Woods keep the proceedings unpredictable, resisting horror movie clichés so that, even if you think you know what might happen next, you’re probably wrong.

While Reed’s ideas could be found in any college-level religious history or theology course (Maybe he was a professor at one point?), the most confronting of his assertions remains this: “The more you know, the less you know.” This irony thrives in academia, where the more you learn, the more you realize how much you have yet to learn. As it applies to religion, the notion recalls a concept shared in this year’s Conclave, where Ralph Fiennes’ Vatican administrator warns against “certainty.” By definition, faith requires embracing doubt, whereas certainty is dangerous and morphs into a controlling mechanism when people stop questioning their beliefs. These lessons extend beyond Reed’s claim that religion is a mere controlling apparatus to social, cultural, and political beliefs. However, the filmmakers don’t endorse Reed’s methods or his messed-up plan, even if he raises salient points about the equal dangers of belief and disbelief. Instead, Beck and Woods see the value in faith as something that can work for people and bring them together, even as they challenge you to think about the potential ramifications.

Grant is no stranger to darker roles despite his prominent reputation for romantic comedies, esteemed dramas, and lighthearted fare. His early part in Ken Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm (1988) comes to mind, as does his performance in Roman Polanski’s twisted Bitter Moon (1992). For a long time, Grant was typecast thanks to the success of Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), Notting Hill (1999), and Love Actually (2003). However, starting with some unexpected turns in Cloud Atlas (2012), Grant has spent the last decade playing juicy, often hilarious villains you love to hate, such as his part in Paddington 2 (2017) or the baddie in last year’s Dungeons & Dragons movie. Beck and Woods use Grant’s presence and knack for dialogue to disarm the tension with Reed’s sly humor and mischievous smile. But his likability makes him even more of a threat; he doesn’t look or speak like a monster, even when he cleverly questions religious history and philosophy, even as he coerces his guests deeper into his house to entrap them. Grant is terrific in the role, and Heretic wouldn’t be quite the film it is without him.

Independently financed, and distributed by A24 in the United States, Heretic fits the company’s brand of making artist-driven films that defy today’s commercial imperatives. It’s unique for a few reasons. For one, it’s rare to find a horror film that’s so dependent on dialogue. Along with the limited space of a chamber piece, the film risks being compared to a filmed stage play. Except, cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon, a regular collaborator with Oldboy (2003) director Park Chan-wook, keeps the camera moving with extended, fluid shots. For a film with most of its scenes inside Reed’s house and centered on discussion, Chung makes it look cinematic, delivering the most visually impressive Beck and Woods production yet. That’s also because the filmmakers have plenty in store for viewers to discover. Production designer Philip Messina creates an outwardly shabby, average house, but it’s a geometrical maze armed with hidden timers, locks, and secrets, reminiscent of Buffalo Bill’s home in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Every subtle, loaded detail informs what’s to come, and it’s echoed by the film’s scenes stuffed to the brim with dialogue.

Beck and Woods engage in Hitchcock-level audience manipulation, intriguing us with theological concepts, making us chuckle at the macabre humor, and delivering an immersive experience. For much of the first half or more, I felt the buzz one gets when every component of a film is pushing me in the same direction, giving me no inkling of where it’s going. It’s only slightly disappointing that, when Reed reveals his cards, he’s a monster, albeit one who uses words and deception to control his victims. But Reed’s reveal allows his would-be victims to overcome his logic. Alongside Grant, Thatcher and East bring subtle layers to their characters, and their outward appearances give way to intelligence and insight. The way Heretic plays viewers throughout results in an incredibly accomplished film, ushering its characters and the audience into a veritable Dante’s Inferno, going down ever further until revelatory moments worthy of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. In its blend of religious discussion and horror chills, few recent commercial films have been so thought-provoking and thrilling to behold.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review