Hereditary

By Brian Eggert |

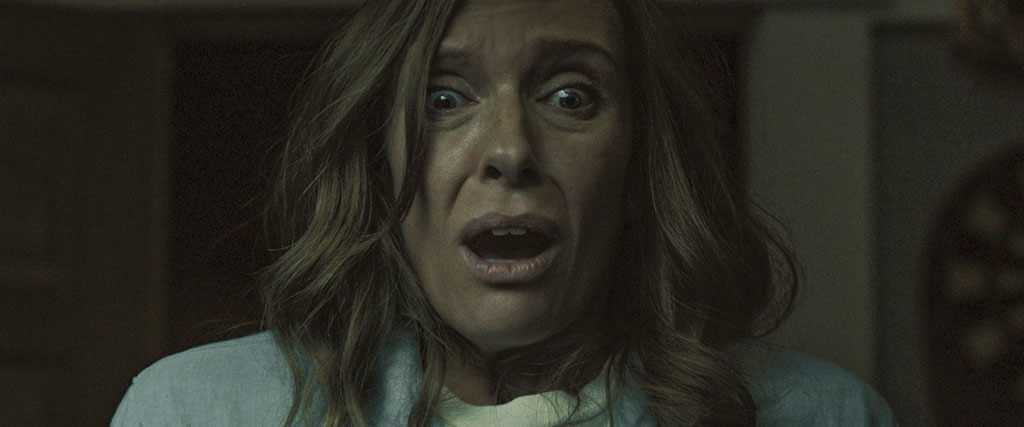

The distributors at A24 have done a marvelous job marketing Hereditary, a horror film that debuted in the Midnight category of the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. Those who avoid reading much about movies before their release often find themselves knowing exactly what to expect by the time a new title makes it into theaters. Trailers tell us everything, so we know exactly what we’re paying for—or at least what we think we’re paying for, since previews often amount to misrepresentations. A24, an indie company that emerged in 2013 and has since released some of the most exciting and original films in the last five years, avoided telling audiences much about Hereditary beforehand. Clips showed us star Toni Collette howling in terror, a strange girl making a clucking sound with her tongue, someone on fire, a teenage boy screaming, and bizarre imagery that didn’t register as any kind of familiar horror subgenre. That’s the best way to see this film, going in without a clear understanding of its hook, and A24’s promotional campaign piqued interest without giving anything away.

With that in mind, if you haven’t seen it, do yourself a favor: stop reading and see the film. It’s best to see Hereditary without even a one-line synopsis or any idea of its central gimmick—especially since the source of its scares isn’t revealed until late in the film, leaving the audience enrapt in a sense of What the hell is going on here? First-time writer and director Ari Aster makes an assured debut; he delivers a formally confident story within a detailed family dynamic, and thoughtfully conceived visual metaphors to reflect them. The horror erupts from his characters, their relationships, and sometimes cruel behavior toward one another, as opposed to some random external force exacting its influence on the family. Their twisted, broken feelings toward each other lay the groundwork for something even more blood-curdling, all of it pouring from raw emotions, captured by the impressive cast, led by Collette, and photographed in dark precision by Pawel Pogorzelski.

The setting is a large home surrounded by acres of woodland and grassy hills. The first shot peers out of a window at a treehouse before turning inside among the trappings of an artist’s workshop, where intricately constructed dioramas replicate the home’s interiors. The shot moves toward a small model of a bedroom until the frame performs a kind of magic trick: the scene in the dollhouse turns into real life. Beyond the impressiveness of the visual transition, the symbolic implications reveal the film’s multiple worlds—something larger outside of the characters, watching them. The home is one of rituals and artistry. But the fussy father, Steve Graham (Gabriel Byrne), who insists on shoes-off in the house, remains an outsider next to his artistically inclined wife and children. Annie (Collette), the mother, dominates the home with her creation of miniature art pieces, while her unhinged emotions have a sordid history. Their teenage son Peter (Alex Wolff) plays music, but he doesn’t trust Annie due to a betrayal from the past. Their younger teen daughter, Charlie (Milly Shapiro), carries haunted features; she’s an odd one, always munching on chocolate bars, assembling twisted little sculptures, or drawing demented pictures in a sketchbook.

The Grahams might be cursed; misfortunes follow them through the generations. In the first scenes, the Grahams attend the funeral of Annie’s mother, a woman whose domineering presence has tormented Annie for some time. Annie has been left with resentment and unresolved tensions toward her mother who, after Charlie was born, insisted on breastfeeding her granddaughter herself. For Annie, Charlie has always been more like her mother’s daughter, whereas her own relationship with Peter remains distant at best. With her mother now gone, Annie begins to learn more about her, looking through her things to find a book on “Spirituality” and a cryptic quote that reads “our sacrifice will pale next to the rewards.” Curious symbols appear in and around the house, and the camera finds strange words like “satony” and “zazas” scrawled on the walls. Annie tries to find some solace in a support group for people who have lost family members and, despite her initial hesitance, she delivers an outpouring of her family’s troubling history with tragedy, mental illness, and inexplicable death—a history she has perhaps never verbalized.

The Grahams might be cursed; misfortunes follow them through the generations. In the first scenes, the Grahams attend the funeral of Annie’s mother, a woman whose domineering presence has tormented Annie for some time. Annie has been left with resentment and unresolved tensions toward her mother who, after Charlie was born, insisted on breastfeeding her granddaughter herself. For Annie, Charlie has always been more like her mother’s daughter, whereas her own relationship with Peter remains distant at best. With her mother now gone, Annie begins to learn more about her, looking through her things to find a book on “Spirituality” and a cryptic quote that reads “our sacrifice will pale next to the rewards.” Curious symbols appear in and around the house, and the camera finds strange words like “satony” and “zazas” scrawled on the walls. Annie tries to find some solace in a support group for people who have lost family members and, despite her initial hesitance, she delivers an outpouring of her family’s troubling history with tragedy, mental illness, and inexplicable death—a history she has perhaps never verbalized.

And then it happens—a disturbing freak accident that sets the horror into motion. Aster’s slow build toward this moment avoids any of the cheap tricks of Blumhouse fare; jump-scares and manipulative sound design that artificially ratchet our fright have no place in Hereditary. A prolonged sense of dread builds for much of the film as its nature becomes clearer. Joan (Ann Dowd), a friend of Annie’s mother, also grieving from the loss of a child, offers Annie the chance to contact a lost loved one through a séance. Convinced by the experience of meeting a ghost, Annie tries to impel her family members to believe what she’s seen. This leads to a familiar blend of horror tropes, expertly employed by Aster without the usual gimmickry: the eerie appearance of figures watching from a distance, spectral light, images associated with witchcraft, talk of demon possessions, and an attic with a disturbing secret. And just when we think we understand the film’s horror rules, the rules change, and it develops into something far more disturbing than we could have imagined.

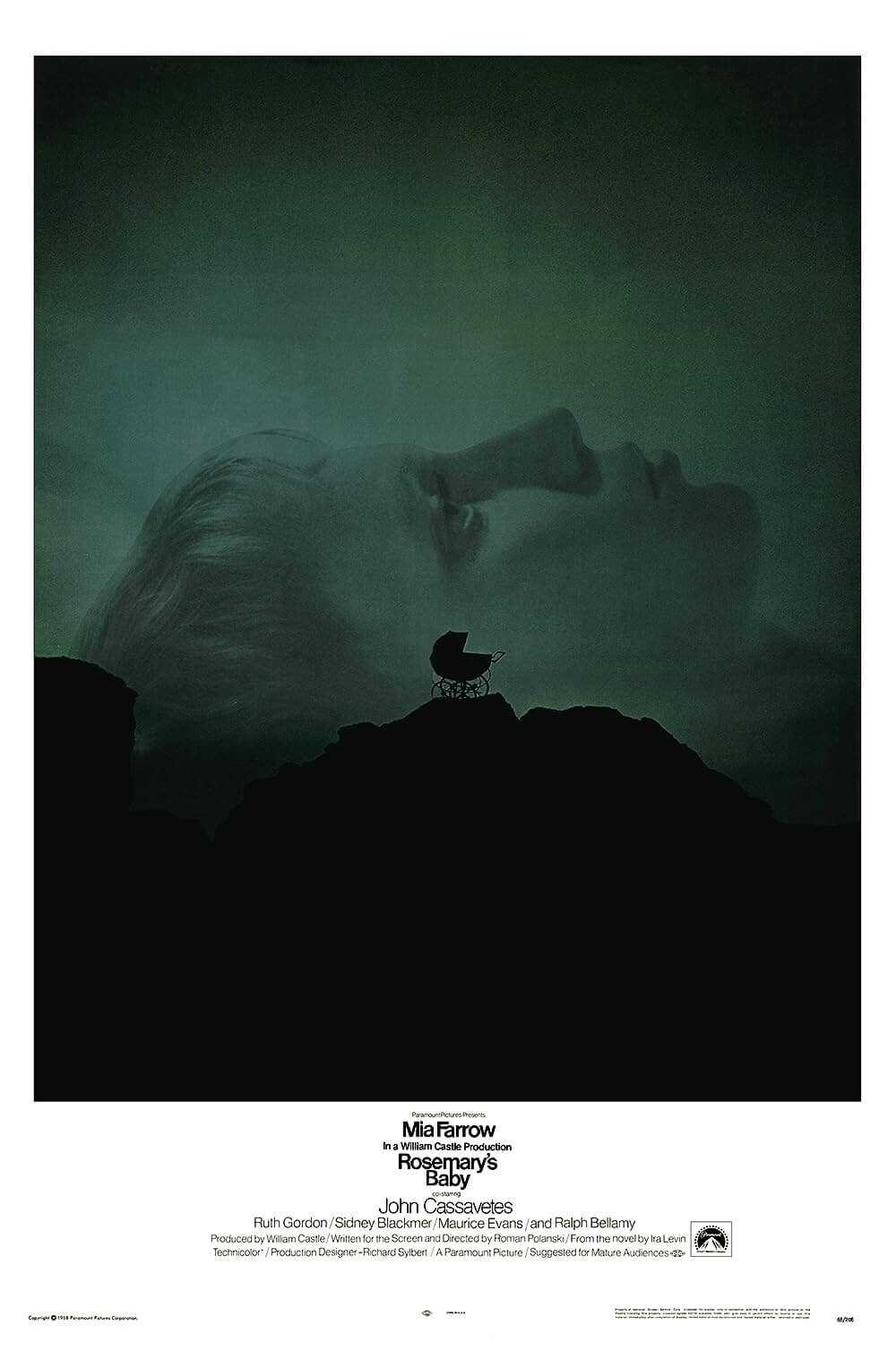

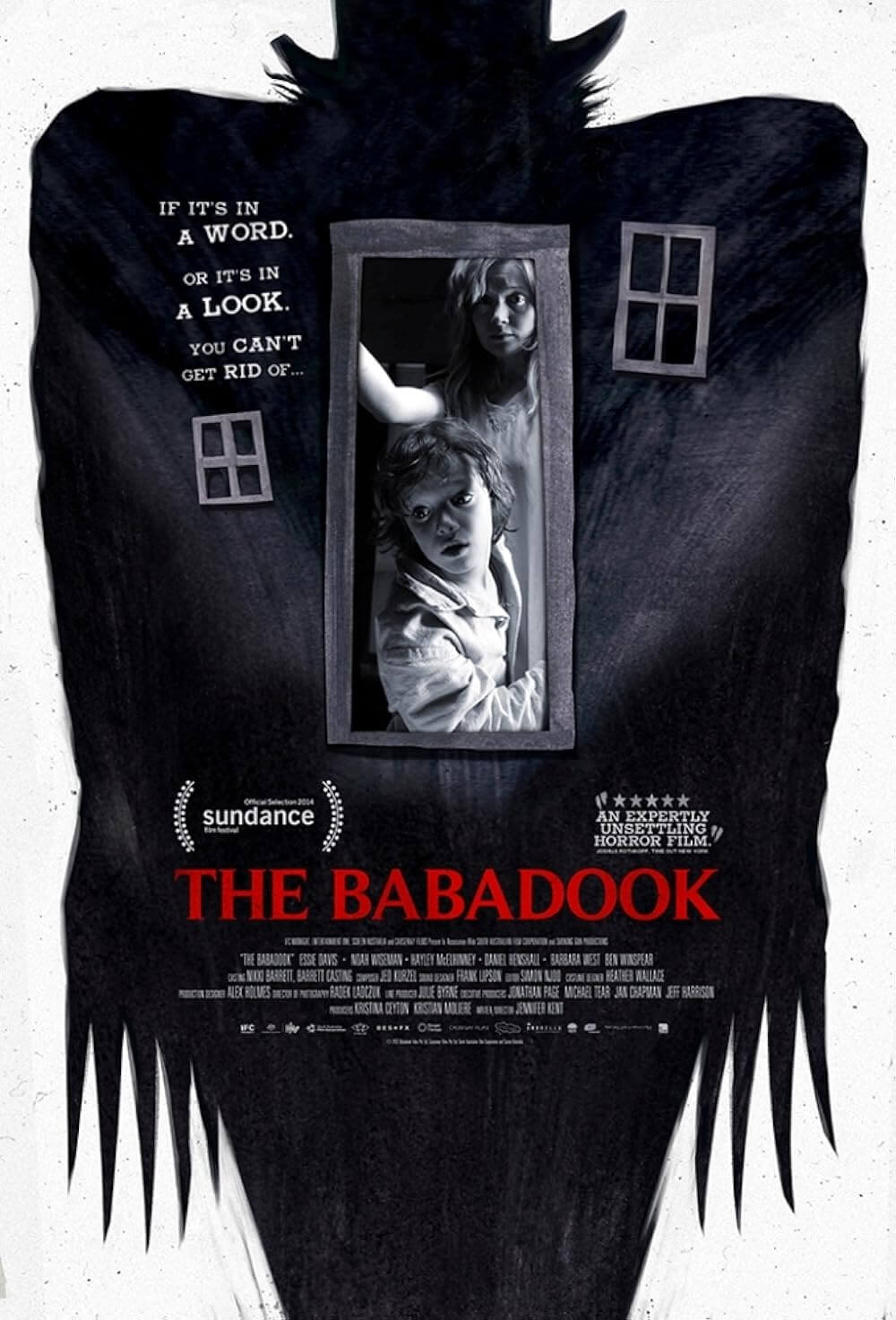

But rather than introduce the horror elements as an oppressive force on the Grahams, the horror in Hereditary emerges from their emotions, fraught psychological hang-ups, and damaged family relations. It recalls the progression of demonic forces in The Exorcist (1973) from the internal states of its characters. To be sure, Aster borrows several moments from the genre’s most celebrated films. Throughout our discovery of what’s going on, he creates the same sense of paranoia and doubt that Roman Polanski engineered in Rosemary’s Baby (1968). At any moment, it might be entirely plausible for Annie’s belief in the supernatural to be justified, but then again, we wouldn’t be shocked if it turned out that her greatest fears lie in her head. Annie’s behavior and their family history validate a plausible doubt among others, making for heightened moments where Annie tries to convince them that something real is happening. But if there’s anything flawed about Aster’s approach, it’s his obvious use of horror touchstones as influences, particularly in the finale that shares tonal and situational similarities with the ending of Rosemary’s Baby. Elsewhere, Aster evokes Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976) in a scene that recalls the famous “It’s all for you, Damien!” moment with the equally creepy line, “I expel you!”

When so much of Hereditary has been expertly crafted—from its measured pace to its use of omnipresent moonlight that brings night scenes to vivid clarity—Aster’s choice to mirror such famous scenes in his film, as opposed to using them as inspiration to create something altogether new, proves disappointing. Audiences expecting run-of-the-mill horror will be shocked out of their moviegoing complacency early on, while the last fifteen minutes may test the otherwise carefully preserved suspension of disbelief. Nevertheless, the film’s purpose, built in gradual pieces throughout, leads to disturbing sights and revelations, the unflinching and uncanny sort that will compel viewers to gasp and cover their mouths. Aster demonstrates with this astoundingly confident first film that he’s a promising new talent, and what’s more capable of orchestrating emotion, the fantastical, and the appalling in a prolonged mood of uncertainty—all leading to a chilling grand design. But his most brilliant stroke must be Collette, who spares no raw emotion or gut-wrenching scream in her outstanding performance, while simultaneously selling every implausibility along the way. Hereditary is exciting for how it accomplishes something that could be too easily described as a horror film about witchcraft and malignant spirits, but as A24 recognized, it’s much more than that.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review