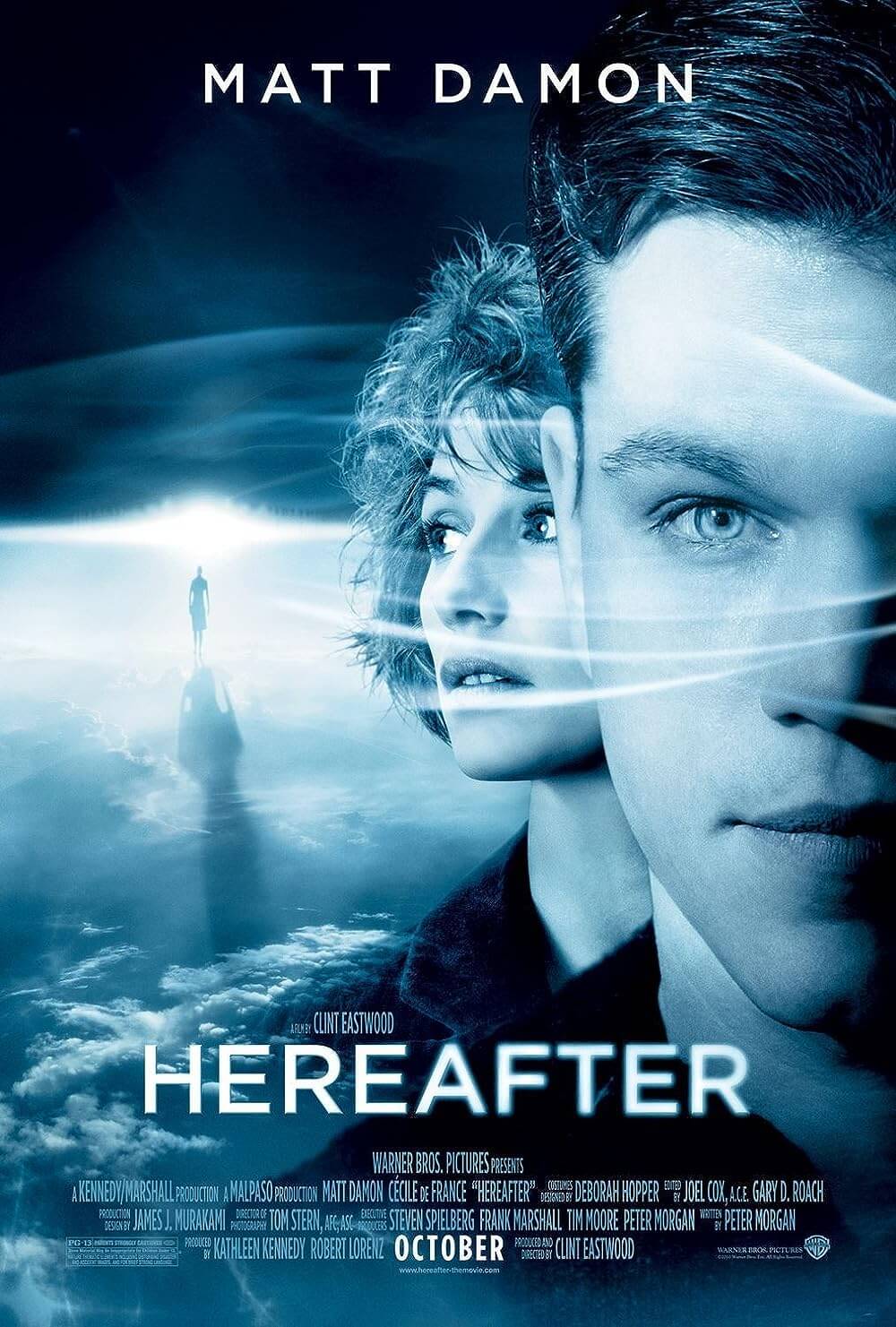

Hereafter

By Brian Eggert |

Clint Eastwood’s Hereafter dwells on characters affected by death with the patience and insight of a master. The former hard-edged actor behind Dirty Harry and The Man with No Name has become the most intuitive of directors, telling his calmly flowing stories with assured hands. His is a patient film, a spiritual film—a film that avoids religious implications and instead confronts basic human questions. He avoids turning central plot elements, such as psychic abilities and a near-death experience, into mere devices. Instead, he advances with equal fascination and respect for his story and characters. As his directorial efforts in the last several years have confirmed, even at his poised version of 80, Eastwood continues to grow as an artist, expanding his horizons through the material he chooses and the way in which it’s presented.

Eastwood’s film opens with a sequence that one wouldn’t usually expect from his work. A slowly building progression leads to the bravado arrival of a tsunami on a vacation island, where French anchorwoman Marie (Cécile De France) is swept away by the sudden wave, nearly drowning from her ordeal. In fact, she does drown, and she dies, but she’s revived by two good Samaritans, only to find that in her brief moments of death, she experienced something. In the scene, water bursts through the village markets; the camera rushes along with the water; explosions crash in the background as Marie is carried through falling debris by the current, witnessing the horror unfold all around her. The sequence feels epic, not how one would describe Eastwood’s usually solemn films. One can’t help but speculate that the film’s executive producer, Steven Spielberg, gave Eastwood a few pointers on the tsunami sequence.

Revolving around three characters, the story’s arrangement takes time to form before its shape is anticipated by the audience. In France, Marie’s traumatic experience has forced her to ask existential questions that her sales-minded employers aren’t interested in asking. She leaves her job as a popular reporter and sets out to write a book on the scientific study of the afterlife. In London, the bond between 11-year-old identical twins Jason and Marcus (George and Frankie McLaren) is split when Jason dies. Marcus is left alone, missing the crucial other half of himself and pondering how he can get in touch with his brother. And in San Francisco, George (Matt Damon) has given up his life as a psychic, despite an authentic talent for speaking to the dead. His brother (Jay Mohr) wants to make his brother’s gift a business again; he was formerly a low-grade John Edwards type. But George considers it a curse to make a living on death, as all of his relationships fall apart because of his abilities.

It takes some time for these fundamentally connected but geographically separate stories to come together, but when they do, they offer some of the most woeful, moving scenes in any Eastwood film. Damon and De France give remarkable performances, and the mere sight of the grief-faced McLarens is bound to put knots in the stomach. Screenwriter Peter Morgan, normally associated with political dramas such as Frost/Nixon and The Queen, handles his topic with vital seriousness and profound humanity. Whereas another filmmaker may have dwelled on the supernatural elements, Eastwood integrates them into the story effortlessly, rendering a story that further absorbs us with each new scene.

Leaving the screening afterward, the audience shared their audible disdain for the picture. “That was boring” and “I certainly wasn’t expecting that” and “Clint won’t be earning any awards for that one” were some of the comments heard. Eastwood’s pacing and meandering narrative structure suggest that an audience accustomed to mainstream Hollywood cinema, not the least of which includes Eastwood’s earlier films, will find the presentation sluggish. His presentation here has been described as characteristic of French dramas, and it’s hard to argue with that assessment. Perhaps it was an error for Eastwood to open with his incredible tsunami sequence, as its tone shares little in common with the rest of the film; everything afterward moves at Eastwood’s usual, casual pace. And perhaps it was an error to rove as he does in the middle, lingering on character-building subplots more than the film’s overall themes. But the director wants the story to take its time, for the audience to become fully immersed, and for the overall effect to be one of submersion.

For this reason, audiences will be split on Hereafter, either fully engaged in the emotions and questions purveyed onscreen or disengaged by the lack of frills after the tsunami sequence or simply resistant to the subject matter. Yet, Eastwood isn’t directing for an audience that expects quick cuts and a runtime of 90 minutes or less. Eastwood is telling the story through his characters and giving each of them their due. There isn’t a character onscreen that doesn’t have more than one dimension. This is a sophisticated, worldly perspective on questions that everyone asks sooner or later. With his experience and wisdom, Eastwood poses them without becoming preachy or gimmicky; but he does test his audience, and likewise rewards them for facing the challenge.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review