Here

By Brian Eggert |

A good magician tells you they’re about to perform a trick. And even though you’re prepared and looking for signs of how they do it, the resulting illusion leaves you breathless anyway. Robert Zemeckis has staged an elaborate magic trick in Here, an adaptation of Richard McGuire’s graphic novel. Almost the entire film unfolds from the same angle, looking at the same spot on Earth, while the story spans several millennia, ranging from the opening scenes in the age of dinosaurs to the outbreak of COVID-19. This meditation on the impermanence of existence, the interconnectedness of all life, the fleeting nature of time, and the vital role memory plays in people has more than a little in common with Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) and the Wachowskis’ Cloud Atlas (2012). To visualize the project’s ambitious, existential premise, Zemeckis’ digital effects supply the sole location and his actors—among them his Forrest Gump (1994) leads Tom Hanks and Robin Wright—with new façades every few scenes. Except, the viewer is always aware of how the film’s resident magician has achieved his illusion; what’s more, the trick is seldom wowing, robbing the material of its intended wonder and introspection. Nevertheless, I admire Here for its ambition and the attempt at something new.

Ever since he undertook the challenge of integrating live-action and hand-drawn animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Zemeckis has been testing the limits of what filmmaking technology can achieve, sometimes with mixed results. Apart from James Cameron, few other filmmakers of the modern age have resolved to be blockbuster directors and experimenters with the medium. Amid his inspired innovations, Zemeckis was among the first directors to embrace computer-generated imagery in early film productions from Back to the Future Part II (1989) to Death Becomes Her (1992). He used similar technology to place the titular character in Forrest Gump into famous historical moments, much to the delight of ’90s audiences and Oscar voters. At other times, his trickery is more straightforward, such as using most of Cast Away (2000) to remind us that Tom Hanks doesn’t really need costars to command our attention. However, not all of the director’s technical innovations have been so celebrated. Consider his nightmarish motion-capture effects used on The Polar Express (2004), and then his doubling-down on the technique with the equally off-putting Beowulf (2007), A Christmas Carol (2009), and Welcome to Marwen (2018).

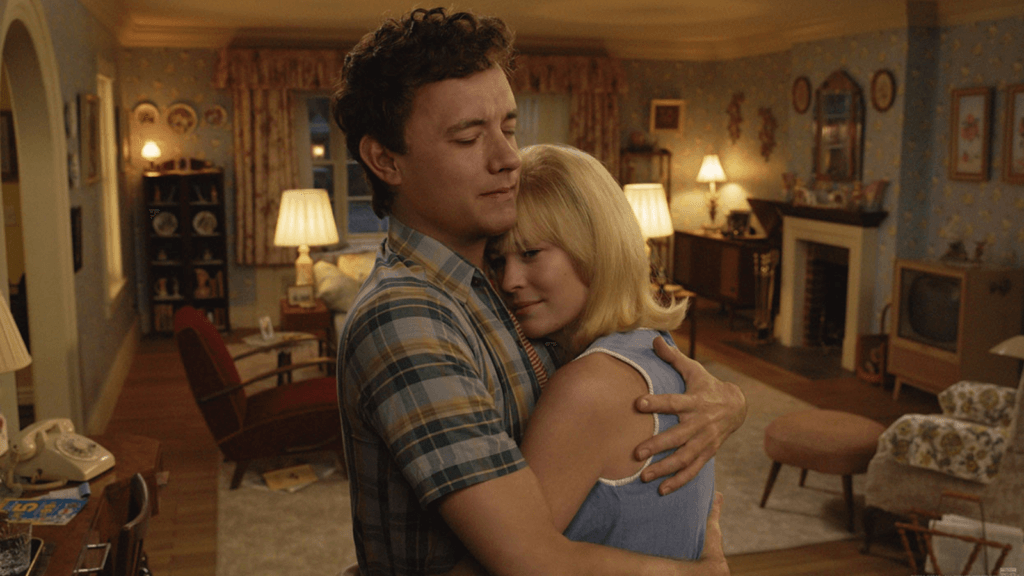

Zemeckis deploys comparable innovations in Here, from relying on the audience-friendly presence of Hanks to wielding technology that de-ages and ages-up his cast. But this isn’t a typical digital effect seen in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019) or so many MCU titles. Zemeckis worked alongside Metaphysic, a VFX studio that uses AI to create what they call “digital makeup” for actors by drawing from thousands of archival photographs—having been given the actors’ permission to use their likenesses. Whereas de-aging graphics are usually applied during post-production, Metaphysic created a system that allows Zemeckis to watch the effect during principal photography so he could see the result live. While no questions about ethically sourced performances arise (unlike this year’s Alien: Covenant), it’s no less chilling and, in the end, unremarkable looking. When the younger versions of Hanks and Wright’s characters appear, the actors hardly look like themselves from, say, Big (1988) and The Princess Bride (1987). The voices and postures of Hanks and Wright, for instance, sound like those of people in their late 60s and late 50s, respectively.

As for the story, McGuire’s comic reaches for the stars, transcending time yet at a single point in space—the corner of a living room in an American house. But that spot hasn’t always been a house. Over the years, volcanic rock and prehistoric forests from millions of years ago, populations from before Europeans settled, and various American families have inhabited this space. Raw, a comics magazine, published McGuire’s initial six-page run in 1989, which he later expanded into a graphic novel in 2014, testing the boundaries of what it means to be a comic. Select a random page of McGuire’s work, and it might contain glimpses of this spot in 1986, 2014, 1938, 1969, and 1352. The association draws connections and underscores differences over vast periods that, on the so-called Cosmic Calendar, amount to mere blips. McGuire’s use of story is nonlinear and arguably non-narrative, delving into a conceptual representation of time and humanity—a cross-section of birth, life, death, and everything in between.

To whatever lofty heights Here may aspire, Zemeckis and co-writer Eric Roth (Forrest Gump) offer a comparatively less experimental and more straightforward presentation. Certainly, it’s more unconventional than your average Hollywood movie, but the screenwriting requires less of the viewer than McGuire does of his readers. Zemeckis and Roth present dialogue teeming with clichés and dramaturgy that occasionally plays like a bad kitchen sink drama performed by a community theater. The sheer number of time-related adages becomes distracting—everything from “It was a different time” to “How time flies.” Elsewhere, the soundtrack is on the nose, such as when Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Our House” plays on the radio, reminding us that, indeed, this house has had many owners over time. This is experimental cinema made for mainstream audiences, and in that respect, aside from some awkwardness, it’s worth celebrating the attempt. Hollywood seldom tries anything new with form or narrative structure, but Here is a film that challenges its audience with something different.

Meeting McGuire’s material at the intersection of graphical art and commercial cinema, Here replicates the comic’s style of panels within panels, like having multiple web browser windows of various sizes open on your desktop at the same time. Each is presented with a thin white border, and most supply a glimpse at the scene to come. The experience is like watching a series of living dioramas, with the outdoor scenes resembling a natural history museum exhibit that’s come to life. Looking at the same spot, we see it was home to an Indigenous couple (Joel Oulette, Dannie McCallum); sits across from the historic home of Benjamin Franklin’s illegitimate son, William; and after the colonial abode was constructed, housed several families. Among them are the Harters (Gwilym Lee, Michelle Dockery), a 1910s couple whose respectable life is upset by the new invention of airplanes. A cute couple of bohemians, the inventor Lee (David Fynn) and his charming partner Stella (Ophelia Lovibond), live the good life in the early 1940s. But most of the 104-minute runtime involves the Youngs.

After World War II, Al Young (Paul Bettany) and his pregnant wife Rose (Kelly Reilly) purchase the house and raise several children. Al is a salesman worthy of Arthur Miller; he drinks too much and doesn’t begin to assess his choices until it’s too late, if ever. Sometime later, their oldest, the teenage Richard (Hanks), introduces his girlfriend, Margaret (Wright), and their faux-youthful appearance exposes the limitations of Here’s technical conceit. They marry, have a child, and, like many Baby Boomers did, they forgo their dreams for myriad reasons. Taking after his father, the risk-averse Richard is obsessed with taxes and never justifies buying their dream house; the couple lives with Al and Rose instead. Margaret feels trapped in Richard’s parents’ home, wanting a space—not to mention a life—for herself. Meanwhile, as time passes, they grow older. All those hopes and dreams become regrets. Sometime after the Youngs, the Harris family moves in, and this couple (Nikki Amuka-Bird, Mohammed George) must deal with a pandemic and a stern conversation with their son about how, as a Black teen, he should handle a traffic stop to avoid provoking trigger-happy cops.

If this sounds like boilerplate drama, it is, but it’s also affecting despite itself. The score by Alan Silvestri, Zemeckis’ longtime composer, rings of those airy, obvious emotional cues that tug at the heartstrings. Still, production designer Ashley Lamont creates a veritable study of how interior decorating can make a space look larger or smaller, depending on the colors and furniture; his choices in the various eras represented keep the room ever-changing, alive, and full of variety. Cinematographer Don Burgess’ crisp lighting conditions sometimes accentuate that the actors in the foreground seem to be performing against a digital backdrop—especially in the pre-house scenes set centuries ago. And if the sometimes stilted dialogue and stagy performances prove awkward, they receive little assistance from the effects (the CGI animals look particularly wonky). Zemeckis and editor Jesse Goldsmith move between panels and scenes with graceful fades and clumsy transitions, which brought Michael Jackson’s “Black or White” music video to mind. Sometimes, the effect looks uncannily good; sometimes, it’s straight from the Uncanny Valley.

Even as I try to resist taking an anti-digital or anti-AI stance, as many critics no doubt will, the artificial look of Here doesn’t make having an open mind toward emerging technologies any easier. Whereas one can be assured of McGuire’s hand-crafted work in the graphic novel, the film represents the aesthetic antithesis of its source material. Its execution presents one digital hurdle after another, challenging the viewer to focus on the narrative and not get distracted by its form. This might be downright impossible, given how thoroughly computer software has manipulated most of its imagery, no matter how inconsequential. But more than Zemeckis’ recent, abortive work on Pinocchio (2022) and The Witches (2020), Here is admirable in its experimental ambitions, despite its ultimate failure. Regardless of how often the presentation and techniques on display distracted me, I found several sequences quite moving. Maybe I’m getting reflective, making this material relatable, or maybe the film’s earnestness burned through my chilly exterior, but I was moved, regardless of how clunky the writing can be. If the trick ultimately doesn’t achieve the full, intended result, it’s an attempt so fascinating, if maddening in its failure, that it demands to be seen and debated. It’s too distinctive to ignore. That’s more than can be said for a lot of movies.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review