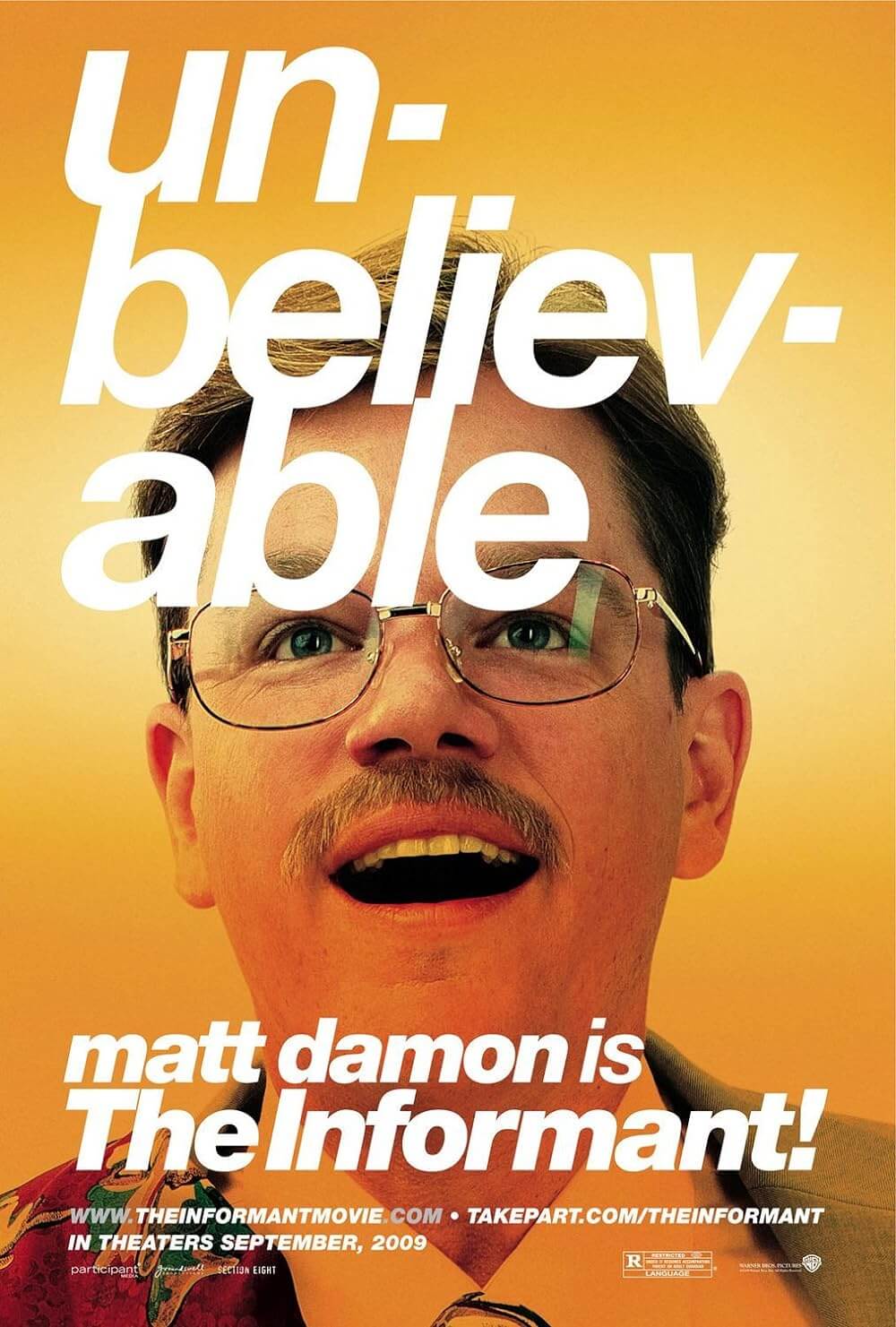

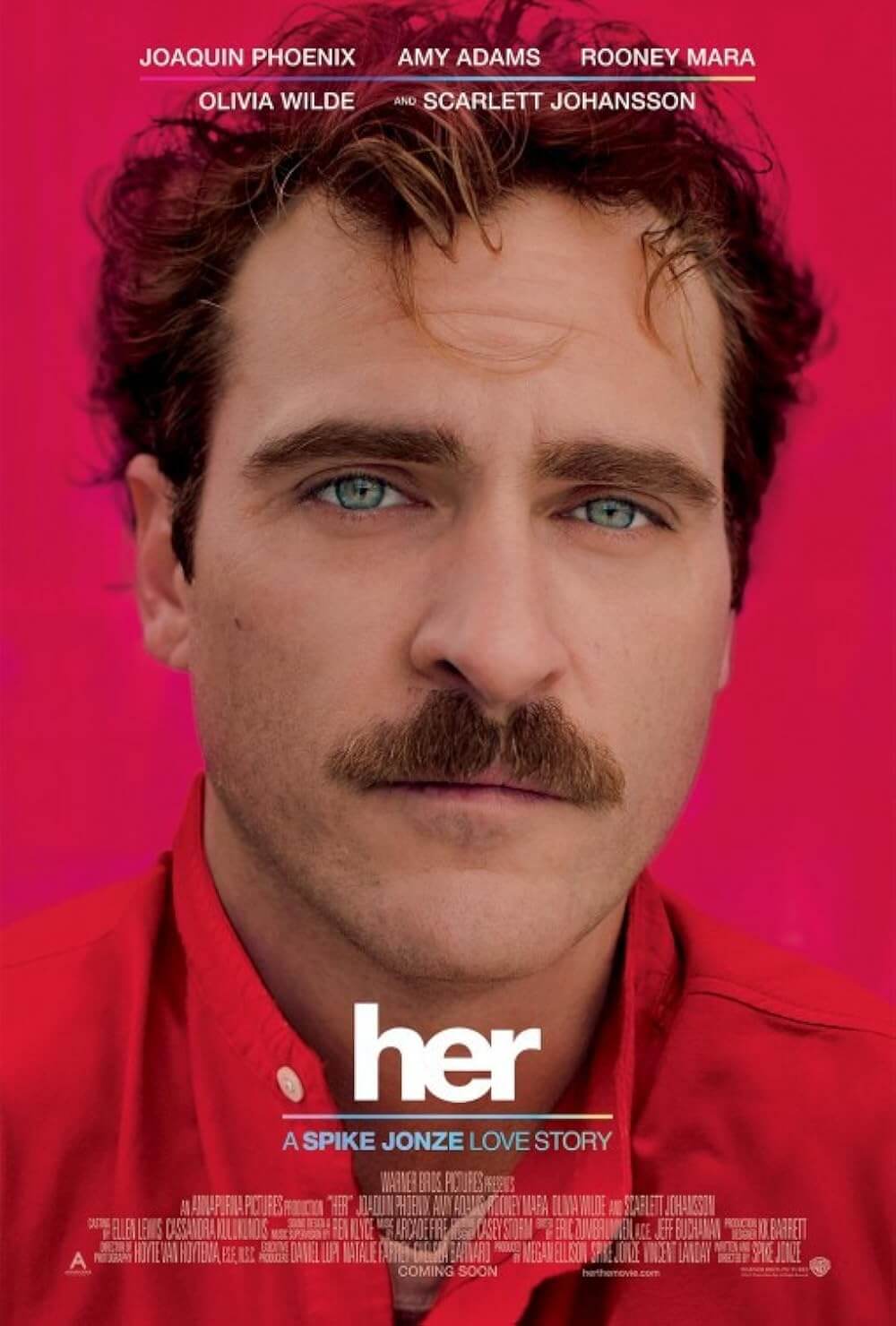

Her

By Brian Eggert |

Theodor Twombly writes for a service called Beautiful Handwritten Letters, where, with profound sensitivity and observation, he dictates personal notes for customers to send their loved ones in faux longhand. Sometime in an undated near-future not too dissimilar from the present, Theodor serves as a proxy for those incapable of composing a thoughtful or heartfelt letter themselves. Alone and melancholy with divorce papers awaiting him, Theodor fills his time with empty videogames and bizarre phone sex experiences, introverted and unable to relate to others. He finds another such filler in the OS1, “the first artificially intelligent operating system.” Upon setup, he answers a few questions about himself, and then a moment later, there’s life, a female voice in his earpiece who names herself “Samantha”. Far more advanced than Apple’s Siri creation, Samantha is a three-dimensional personality, without corporeal form but with access to infinite information and curiosity about the world. But more than that, she has sentience and the capacity to grow. And as his new companion develops, Theodor cannot help but fall in love with her.

Though the material sounds ripe for a pure satire or sci-fi social commentary, the critical aspects of Spike Jonze’s Her reside under a surface loaded with genuine tenderness. Though the high-concept material may be far-fetched, the emotions and characters resonate with considerable truth. Though the subject matter may be unlikely for deeply affecting cinema, Jonze has a reputation for making the unlikely a reality. Consider his previous films, such as Being John Malkovich (1999) or Adaptation. (2002), where Charlie Kaufman’s out-there screenplays reformat real-life into surreality without sacrificing the truth of the human relationships at their center. Or consider Jonze’s adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s storybook Where the Wild Things Are, brought to life through puppetry and vital coming-of-age emotions. As only his fourth feature, Her was based on Jonze’s own ambitious and first solo screenplay, and his efforts fall in line to be every bit as challenging and wonderfully original as his previous films.

Jonze owes the emotional authenticity of his picture to his protagonist, played by Joaquin Phoenix. As Theodor Twombly, Phoenix is a nebbish who sports a pathetic mustache and a lingering air of misery. He lives in a pastel-colored world of lightness and few sounds. People ride quiet trains and there’s nary a car in sight. Modern fashion equates to pants worn high and tops in “the colors of Jamba Juice,” as Jonze himself put it in a recent interview. Humans are exceedingly caring toward one another, seemingly there for infinite support, except these are just gestures. Everyone’s glued to their OS1, complete with an earpiece and small rectangle case with a camera, which is Samantha’s eye. In their first moments together, she asks “You mind if I look through your hard drive?” Reluctantly, he agrees and she quickly organizes Theodor’s email. She reminds him of meetings, sets him up on a date (with Olivia Wilde) that goes wrong, and reads books in two hundredths of a second. But, as sentient computer systems are known to do, Samantha begins to develop feelings. Voiced by Scarlett Johansson, Samantha’s every emotion sounds genuine. And when their newly formed relationship develops, aural sex and all, it’s easy to understand why Theodor finds her so alluring.

Theodor tells people that he’s dating his operating system, but rather than shock or disgust, most respond with understanding. His neighbor Amy (Amy Adams, excellent in her small role) reacts as though a person must find love on the go, having just left her goon of a husband. Love is a “socially acceptable form of insanity,” she tells him, so why not date a computer? His boss (Chris Pratt) suggests a double-date with his human girlfriend. The only person who recoils is Theodor’s wife (Rooney Mara, who rejects the artificial relationship just as her character rejected Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network). But is the relationship artificial or simply different? Is the relationship any less valid if there’s not a tangible body there? Theodor asks these questions as Samantha develops her personality further and her lack of a body becomes an issue—for her, not Theodor. She takes it upon herself to hire a surrogate, a woman (Portia Doubleday) who plays the role of a physical Samantha, to realize Samantha’s sexual fantasies with Theodor, but he can’t go through with it. Before long, as a consciousness who exists in the nothingness of cyberspace, Samantha evolves at an exponential rate beyond Theodor. She begins to meet other sentient operating systems, all forming a group that, were they not tempered by a simulation of late philosopher Alan Watts (voiced by Brian Cox), could’ve developed into Skynet, the computer system that waged war on humanity in The Terminator.

But Her isn’t about the dangers of sentient technology, at least not as a primary throughline. Jonze has constructed a touching love story that contains countless beautiful moments, and during any one of them, we’re ready to laugh or cry or grow hesitant about how real Samantha seems. Their conversations click like any good couple’s; they could be called soul mates, although one feels the need to qualify such a statement. There’s a sequence where Theodor strums a ukulele and Samantha sings some improvised lyrics, and the two find themselves in sync through song. When Theodor goes out, he wears his OS1 in his front pocket so Samantha can see the world. There’s nothing artificial about these moments or the happiness we feel through Theodor. But then, cleverly, Jonze cuts away to show other loners in a crowd of loners, all talking to their operating systems. The audience cannot help but consider the ramifications of deficient human social interaction, as opposed to genuine experiences and feelings had with a computer, on our culture. Albeit indirectly, Jonze provides an answer to our reflection by making Theodor and Samantha’s relationship one of the most emotionally realistic relationships ever put to film.

Phoenix’s utter commitment to his character’s emotional fragility and remoteness around other humans reflects feelings of estrangement shared by countless people in the digital age. Social networks and mobile devices have divided us, leaving technology to fill in the gaps that remain. When he falls in love with Samantha, we do not look upon Theodor as a troubled loser who’s clung to something to fill a gap, like Ryan Gosling’s turn in Lars and the Real Girl. Phoenix’s performance is staggeringly good and three-dimensional, comparable to his transformation in last year’s The Master, where we no longer see the bearded weirdo from his ersatz documentary I’m Still Here, but rather his character’s bared spirit. What drives his performance and the emotional veracity of the film are solitary scenes with his earpiece, walking on the beach, through crowded subway terminals, and on sidewalks with an expansive cityscape in the background. Shooting in Los Angeles and Shanghai, Jonze’s exteriors have soft lighting courtesy of the pristine lensing by cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema, and these images are easy on the eyes. We listen to Theodor’s conversations with Samantha, and Phoenix portrays all the tragedy, heartache, and happiness of someone fatefully in love.

Visionary and touching, Her swells with incredible performances, both physical and auditory, a thorough realization of the future, a brilliant formal acumen that hides just below the narrative, and comic observations about social interaction. On a more basic level, this is a love story in which feelings, though intangible, have far more truth behind them than reality. As landmark sci-fi author Philip K. Dick wrote, “The true measure of a man is not his intelligence or how high he rises in this freak establishment. No, the true measure of a man is this: How quickly can he respond to the needs of others and how much of himself he can give.” Theodor has measureless love to give, his loneliness and distance from others answered by his aching sincerity, both in his “handwritten letters” and his moving conversations with Samantha. At once provocative and fragile, Jonze’s many-layered film leaves us with much to consider about how we love and whom we choose to love, and it leaves us reeling with pleasure over the amazing film he’s made.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review