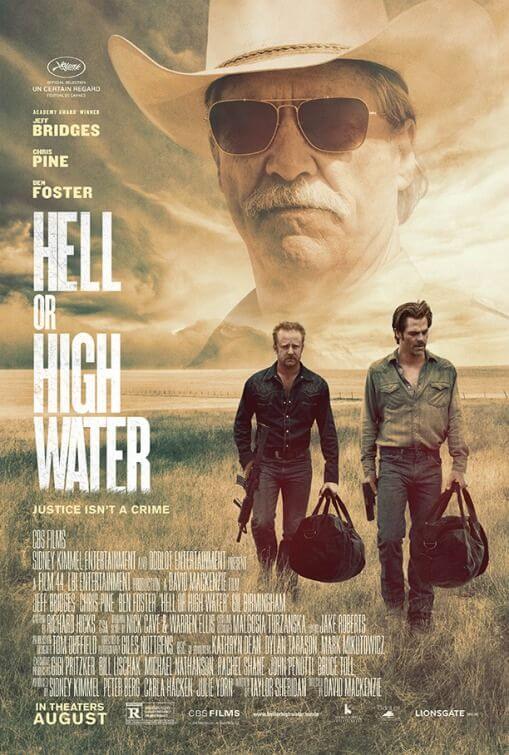

Hell or High Water

By Brian Eggert |

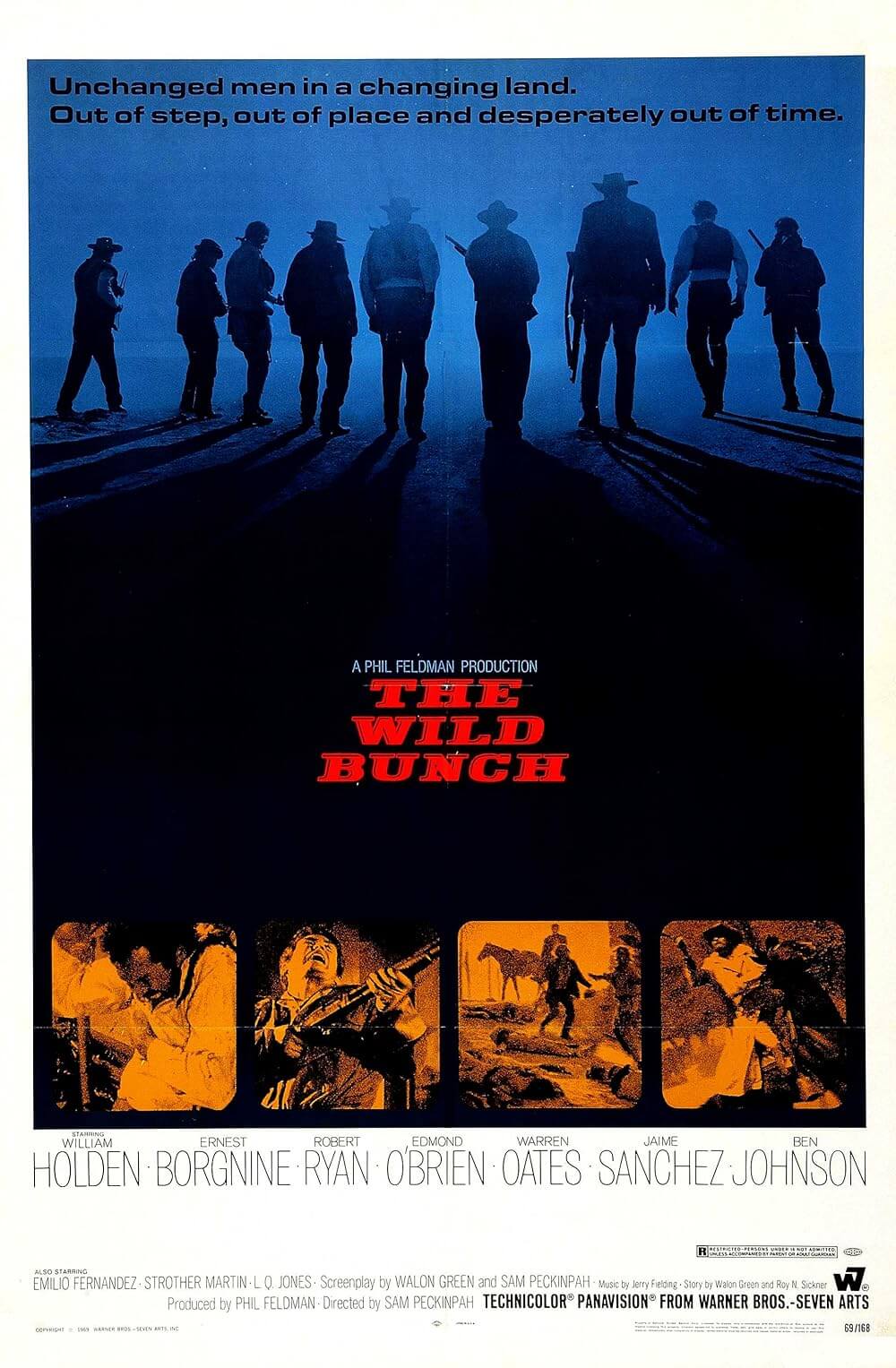

About halfway into Hell or High Water, a modern Western set in rural Texas, the film’s pair of bank-robbing brothers exit their latest score only to be greeted outside by several good ol’ boys with concealed carry permits. Bullets begin to fly, and the film instantly shatters any Hollywood ideas about slick robbers clocking the response time of local police to carry out a perfectly timed heist. Instead, the film considers Texas as a place where the romantic Wild West mythos has spread to all. The robbers believe themselves to be something akin to just outlaws, doing what they must to protect their own. The Texas Ranger assigned to track them sees himself as a classical lawman with a big hat and boots, an archetypal Western hero bringing civilization to the frontier. And undoubtedly, the locals who take arms against the robbers view themselves as unofficial deputies, taking shots at the outlaws from behind their gas-guzzling pick-up trucks. They can’t all be right.

The screenplay by Taylor Sheridan (Sicario) considers each ideology and its moral justifications, focusing on the two brothers, Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster), and the two veteran law enforcers on the case, Marcus Hamilton (Jeff Bridges) and Alberto Parker (Gil Birmingham). They inhabit a sprawling West Texas landscape covered in dilapidated ranches, empty fields populated by the occasional oil pump or herd of cattle, and towns long since thriving. Scottish director David Mackenzie (Starred Up, Perfect Sense) shoots the rural scenery like a post-recession wasteland out of a Cormac McCarthy novel; and while he captures the spare, empty quality of the backdrop, he also uses repetitious, sometimes heavy-handed imagery. On the road, d.p. Giles Nuttgens points his camera out the window of a car to spy signs asking “Need Debt Relief?” Showing one such sign would have reflected how the last decade’s economic crises have affected small-town Texas; the fifth or sixth time this same shot is used, it becomes downright redundant.

After a wallop-of-an-opener in which Toby and Tanner rob two Texas Midland banks in the early morning hours, Hell or High Water eases into a steady, measured pace, taking its time to explore these characters. With a lifetime of crime on his record, Tanner enjoys the rush of taking down scores; he’s mean, doesn’t hesitate in a shootout, and seems like he always has something to prove. Foster plays him like a less intelligent version of his maniacal lapdog role in 3:10 to Yuma (2007). Toby is different, more pensive, and clearly carrying a weight on his shoulders. He doesn’t seem suited for criminal life, unlike his brother. And yet, Toby masterminded their strings of robberies, which are more calculated than they first appear and later establish the robbers as avengers of financial injustice. Pine is quietly effective in the role and far removed from his brash, overconfident Captain Kirk.

Toby’s scheme involves morning robberies for a series of banks in the area, and limiting themselves to lower-quantity bills from the register (nothing traceable). After each robbery, they ditch their latest in a series of getaway cars, each stolen beforehand and then buried immediately following their getaway. They clean their cash at a casino, and then exchange their “winnings” for a check made out to—where else?—Texas Midlands bank. Toby plans to pay down the mortgage and back-taxes on their late mother’s ranch, and then sign over the property to his two sons. The land has oil, and in order to protect the black gold for the future of his children, he intends to place the property in a trust. And after hearing endless remarks about how the banks caused the recession, leaving West Texas a place of rampant unemployment and visible squalor, Toby and Tanner might seem sympathetic, even after a few deaths occur during their robberies.

Bridges once again adopts the vocal inflection he created in Joel and Ethan Coen’s True Grit (2010)—that southern-fried, shit-in-his-mouth voice that was effective upon its first use, but has grown tiresome when repeated on R.I.P.D. (2013), The Giver (2014), and Seventh Son (2015). Once you get beyond how annoying Bridges’ voice sounds, you may be able to find a kind of Texas nobility in his role. Then again, you may just write him off as a racist old shitkicker in his final days before retirement. Hamilton dishes out no end of slurs against his half-Mexican, half-Comanche partner, his remarks intended as friendly teasing, though they often become mean-spirited and clearly bother Alberto. For Hamilton, his relationship with Alberto marks an outdated idea of the white master and the dark-skinned savage, and despite a few moments of quiet laughter between the men, theirs is a generally unpleasant friendship while it lasts, with much left tragically unsaid. Meanwhile, Hamilton’s interactions with two very different waitresses, Katy Mixon and Margaret Bowman, the former trying to preserve her $200 tip from Toby, the latter a no-nonsense type, are priceless.

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis produced the film’s music, which adds another twangy country layer to the material—though not as soulful as Cave’s work on The Proposition (2005). Nuttgens shoots in an unfussy style, allowing the actors to take center stage, save for a couple of wonderfully choreographed robbery sequences. Comparisons to Unforgiven (1992) and No Country for Old Men (2007) may ensue given its similar tone; however, the film is less interested in exploring the karmic ramifications of the narrative, and barely addresses how these characters both inhabit and reject Western tropes. Still, Mackenzie describes his film’s characters with richness and depth, and each is afforded gradations by both the screenplay and performances. Although the story offers a few surprises, watching Hell or High Water is about watching Pine ruminate on his actions, Foster play the wildcard, and Bridges apply his charm with several witnesses. On the basic terms of scenery-chewing actors making the most of their respective onscreen presence, Mackenzie’s film is a small victory.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review