Hard Truths

By Brian Eggert |

Mike Leigh returns with Hard Truths, the sort of material he started writing and directing over 50 years ago with his debut feature, Bleak Moments (1971). Since then, he’s earned a reputation for kitchen-sink dramas and sharp examinations of human behavior, which has lasted much of his career. However, for the last decade, Leigh has been associated with exquisite period dramas, such as his painter biopic Mr. Turner (2014) and the underseen and underappreciated—but utterly vital—Peterloo (2018). His new film might be considered a return to form, but then again, every Leigh picture weighs complex British characters, whether they’re about historical icons or working-class citizens. His foundation in social realism emerges once again with Hard Truths, a portrait of depression that introduces one of Leigh’s most challenging main characters to date, played by Marianne Jean-Baptiste, who last worked with the filmmaker on Secrets & Lies (1996). And while that film earned Leigh more accolades, including a Palme d’Or, his latest supplies a striking and unforgettable portrait nonetheless.

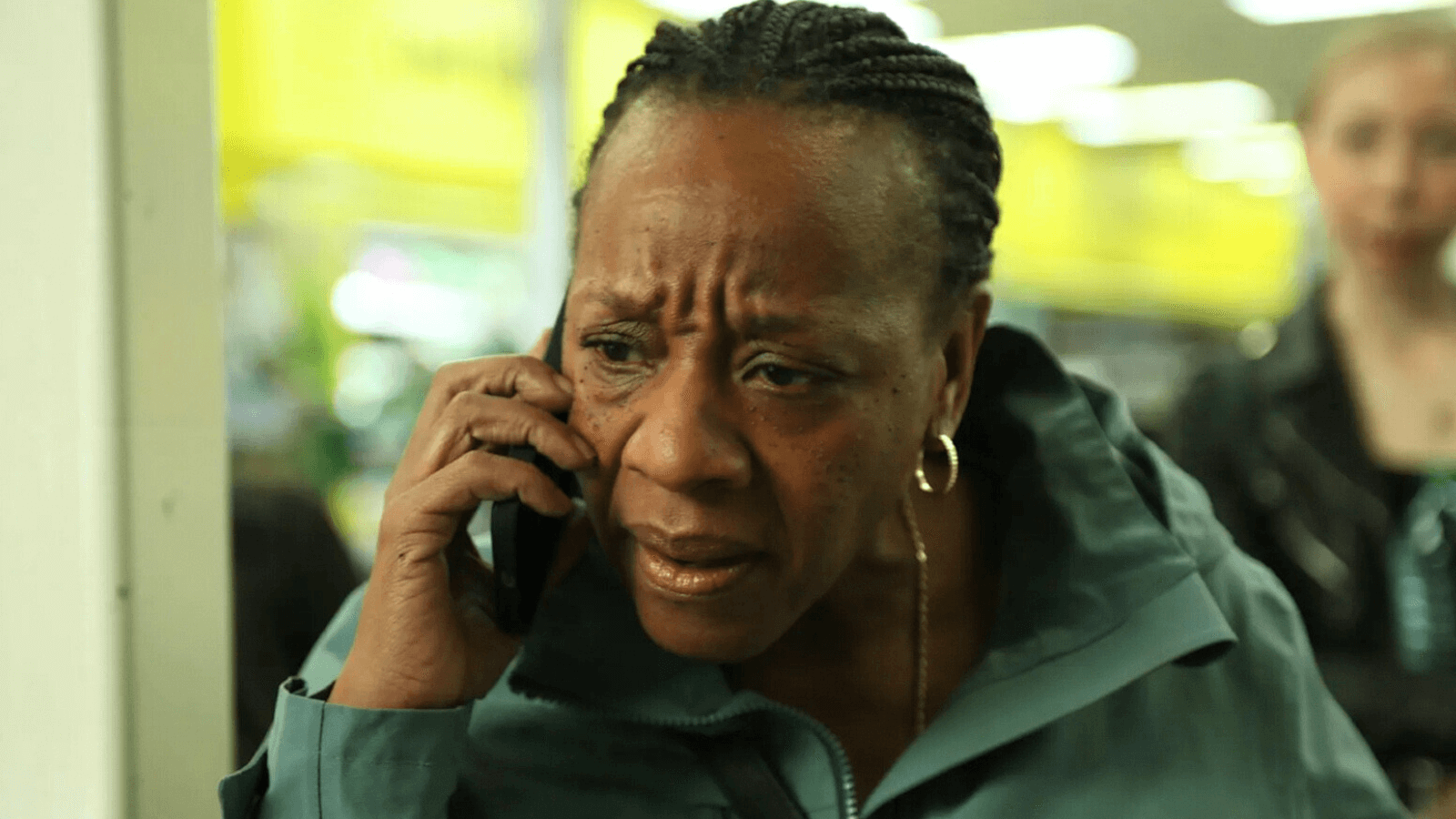

To whatever degree you’re in a good mood when you watch Hard Truths, it will likely be soured by Pansy Deacon, Jean-Baptiste’s wonderfully played and ferocious character whose deep anger turns every interaction into discomfort. When she wakes up in the morning, it’s as though a nightmare has roused her into consciousness. She might even resent being awake. She lives in a tidy, antiseptic-clean home with her husband, Curtley (David Webber), who runs a small plumbing business, and their 22-year-old son Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), an inward and fragile guy who hasn’t found direction. Though, he’s fascinated by planes and aviation. Pansy’s family seems to disappoint and frustrate her, and she constantly scorns them for minor violations. She blames Curtley for Moses’ lack of ambition and for wearing shoes in the house; she accuses Moses of being lazy and messy. She does so with the tone of perpetual disappointment, even dislike. This has gone on for so long that Curtley and Moses no longer argue with her. No matter what they say, it will be wrong, so they resolve to stay silent.

When Pansy goes out, bad things happen to her. “What things?” asks her sister Chantelle (Michele Austin), a genial hairdresser with two kind, good-humored adult children, Kayla (Ani Nelson) and Aleisha (Sophia Brown). “People,” Pansy replies. But it’s less that people affect Pansy and more that she turns on anyone she sees—furniture store employees, doctors, grocery store clerks, and dentists receive her scorn for simply existing. These are difficult scenes to watch, set to the abrasive tone of Pansy shouting harsh, unprompted insults at strangers and service workers. It’s almost enough to ruin any goodwill one might feel for the character, except the film’s second half finds Pansy grappling with her moods on Mother’s Day, when she visits her mother’s grave with Chantelle. “I’m just so tired,” she says. “I just want to lie down and close my eyes. I want it all to stop.” Anyone who has suffered from depression or has known someone who does can relate.

Several of the characters in Hard Truths are types that Leigh has explored before. The irritable Pansy reminded me of Eddie Marsan’s severe, shouting character in Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), who serves as an antithesis to Sally Hawkins’ eternal optimist. Moses shares some similarities with James Corden’s character in All or Nothing (2002), a frustrated and overweight kid whose behavior echoes his family’s and who’s bullied on the street. Thankfully, Leigh maintains his characters’ integrity, never resorting to sensationalism to drive the story or to gimmicky sentimentality to supply a tidy ending. He resists artificial resolution or forced moments to spare the audience. The closest Leigh comes to any emotional breakthrough is when Chantelle tells Pansy, “I don’t understand you. But I love you.” Yet, for someone with depression, not even a declaration of love can soothe the pain.

Hard Truths is the final film shot by the late cinematographer Dick Pope, Leigh’s collaborator for over three decades, since Life is Sweet (1990). Despite the subject matter, the film looks crisp and sunny. It’s Leigh’s visually brightest film since Happy-Go-Lucky, if not more so, and it’s a reminder that no matter how beautiful a day may be, depression makes you want to curl up inside, in the dark, alone—which is all that Pansy wants. The daytime lensing is accompanied by Gary Yershon’s gentle score of limited string and woodwind instruments, suggesting the characters’ sense of solitude, despite being surrounded by family members. The unfussy, minimalist filmmaking allows for subtle gestures that do not go unnoticed, such as Pope’s shot that pans outside the Deacon home at the opening and closing of the film. The movement suggests a framing device, as though we’ve read a storybook called “The Dark Times of Pansy Deacon.”

Leigh has no answers or catharsis for Pansy in Hard Truths; the film doesn’t even diagnose her with depression or, if memory serves, even mention that word. Brilliantly portrayed by Jean-Baptiste in an immersive performance, the character’s bitterness has marred her relationships, perhaps irreparably. Or perhaps her depression is situational, and her realization that he despises her family and life has prompted her depression. Pansy complains that her mother never pushed her to pursue math despite showing an aptitude for numbers, and she resents her for that. Yet Leigh never allows Pansy to realize that Moses has an affinity for planes, so she never becomes a better mother than her own. By contrast, Aleisha and Kayla both learn from their mistakes at work in brief scenes and resolve to fix them, but Pansy doesn’t have the same clarity of mind or perspective. These subtle and nuanced parallels amount to profound human poetry, if also a tragedy, on Leigh’s part. As the title suggests, this slice of life offers no easy answers to the viewer. But when has Leigh ever sacrificed a character’s emotional reality to spare his audience or satisfy their expectations?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review