Happening

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2022 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival.

A young woman contracts “the illness that only strikes women and turns them into housewives” in Happening (L’événement), a timely French drama from director Audrey Diwan. Anamaria Vartolomei gives an astounding performance as Anne, a literature major with a bright future. One of her professors thinks she will teach; she wants to write. Either way, her possibilities and independence remain intact until she discovers that she’s pregnant. Given the film’s setting in 1963 around the city of Angoulême—in a country that criminalized abortions until 1975—Anne’s need of an abortion becomes a desperate and dangerous pursuit. Her independence, career, and the trajectory of her life are at stake. But Diwan resists turning Anne’s story into a soapboxing political statement that telegraphs its meaning into the dialogue or melodramatic speeches; she doesn’t inject political or ideological debates that weigh both sides of the issue against the present-day culture war. Instead, the filmmaker uses unflinching realism and immersive subjectivity to place us into Anne’s perspective. The empathy shown for Anne’s predicament extends beyond the pregnancy; it addresses questions of personal desire, sexuality, and agency over her body and the events that determine the rest of her life.

Writers Diwan and Marcia Romano adapt French writer Anne Ernaux’s memoir of the same name, infusing the material with an aesthetic that creates a bond between the viewer and Anne. She’s already a deeply sympathetic character, but the adaptation removes the book’s segments where the older Ernaux looks back at her life from a critical perspective. Instead, Diwan’s approach immerses us in Anne’s subjectivity through several formal tactics. Cinematographer Laurent Tangy rarely places the camera outside Anne’s bubble, creating a bond between subject and viewer. Whether following behind her or close to her face, the often handheld camera invites the viewer to experience Anne’s perspective within each moment. The filmmakers also use the Academy ratio to superb effect, reminding us that Anne’s world is circumscribed on many fronts. She has fewer choices about her future and body than a young man her age, and the boxy shape of the image, which leaves whole sections of the screen in black, mirrors the possibilities and freedoms not granted to her.

Diwan’s direction places us inside Anne’s experience. The camera practically looks over her shoulder when she checks her underwear and realizes her period hasn’t come for three weeks. When Anne’s doctor breaks the news, she refuses to believe him. “It’s not possible,” she says, and then denies having intercourse. Diwan carefully avoids showing the conception, implanting a moment of doubt, but the doctor has surely seen this reaction before. Finally, she tells the doctor, “Do something.” The request angers him. “You can’t ask me that,” he tells her. “The law is unsparing.” They could both end up in jail. Anne uses the college library to research information about what’s happening to her body, and thus find a solution. But when she asks others for help, the response is cold. Friends Hélène (Luàna Bajrami) and Brigitte (Louise Orry Diquero) tell her, “It’s not our problem.” And so, alone, Anne tries another doctor, who seems unfazed by Anne’s request. He writes her a prescription for a shot that will prompt menstruation. But after several days with no change, she discovers that some deceptive doctors prescribe a solution that strengthens the embryo to protect it against further abortion attempts.

As weeks pass, Anne’s lonely mission continues. She thinks of nothing else, and her grades slip. The pressure is unbearable. If her secret gets out or her efforts prove unsuccessful, it would derail her life. At this time in history, not only would she be forbidden from attending university while pregnant or as a single mother, but French society would expect her to become a homemaker. It’s somehow fitting that Sandrine Bonnaire plays Anne’s mother. In Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (1986), Bonnaire starred as a young woman opposed to any authority whatsoever. Here, the social conditions rob Anne of self-ownership, leaving her no choice but to seek out less professional means. But even asking around can prove dangerous. When she inquires with her so-called friend, Jean (Kacey Mottet Klein), he responds by making a pass at her, arguing that she cannot get pregnant. Anne eventually decides to solve the problem herself, using a knitting needle sterilized with a lighter and a mirror to guide her way. The attempt fails. Still, despite rejecting him, Jean comes through, setting Anne on a path toward an abortionist played by the gravelly voiced Anna Mouglalis—a sort of French Vera Drake.

As weeks pass, Anne’s lonely mission continues. She thinks of nothing else, and her grades slip. The pressure is unbearable. If her secret gets out or her efforts prove unsuccessful, it would derail her life. At this time in history, not only would she be forbidden from attending university while pregnant or as a single mother, but French society would expect her to become a homemaker. It’s somehow fitting that Sandrine Bonnaire plays Anne’s mother. In Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (1986), Bonnaire starred as a young woman opposed to any authority whatsoever. Here, the social conditions rob Anne of self-ownership, leaving her no choice but to seek out less professional means. But even asking around can prove dangerous. When she inquires with her so-called friend, Jean (Kacey Mottet Klein), he responds by making a pass at her, arguing that she cannot get pregnant. Anne eventually decides to solve the problem herself, using a knitting needle sterilized with a lighter and a mirror to guide her way. The attempt fails. Still, despite rejecting him, Jean comes through, setting Anne on a path toward an abortionist played by the gravelly voiced Anna Mouglalis—a sort of French Vera Drake.

Although Happening is about a young woman struggling to arrange an illegal abortion, Diwan also conveys the stigmatization of female sexuality. While cultures accept that college-age men will sow their wild oats, the film’s women have the same desires but cannot act out of fear of the repercussions—both shaming (which Anne endures from her peers in a confronting communal shower scene) and pregnancy. The film’s opening scene shows Anne and her classmates preparing for a night out, albeit in vain, since most of them won’t risk going all the way. Brigitte prefers to use a pillow to masturbate, and she demonstrates how to her friends. Sex has a greater risk for these young women than their male counterparts, and Anne is living proof. Later, Anne’s recognizes how, in her pregnant state, she has a certain freedom. The risk and danger around sex have been mostly lifted, and she takes advantage of that in a random encounter with a local fireman—a rare instance of pleasure without life-altering consequences. Diwan’s acknowledgment of Anne’s sexuality despite—or perhaps because of—her circumstances lends the character a dimensionality that other films about abortion have resisted. Sex, the act that put them in this situation in the first place, is usually the last thing on these characters’ minds.

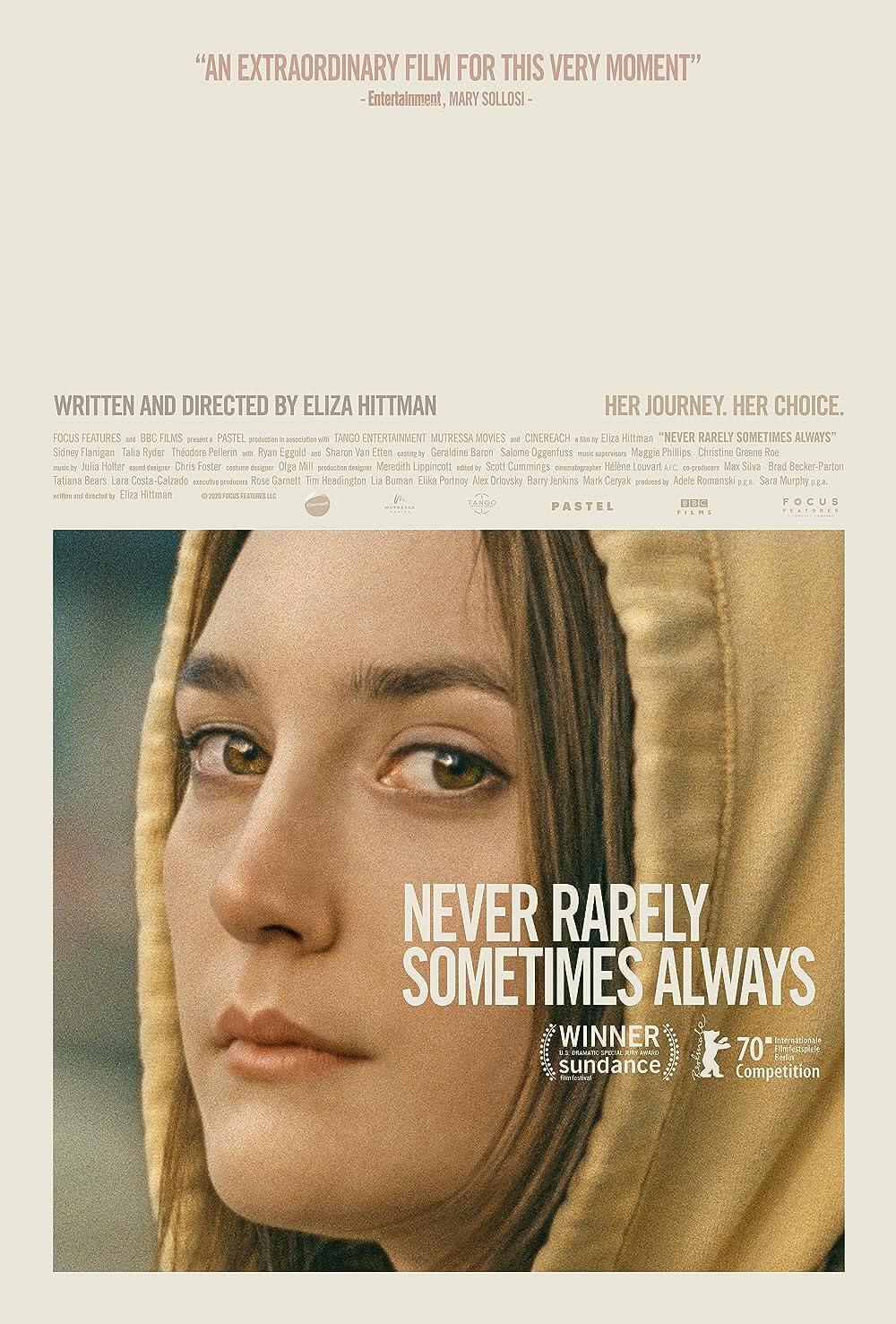

Yet, Happening has much in common with other films that address abortion, including a style of cinematic realism to achieve a sense of gripping reality. Diwan’s film shares techniques with the most memorable of them, Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), in that both aim their cinematic apparatuses in the direction of entrenched individualism. However, Mungiu’s subject isn’t merely abortion but the constrained society of Romania under Communism. Diwan’s approach might have more in common with Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020), which at times feels like guerilla filmmaking in its social realism. While perhaps not as symbolically loaded as Mungiu’s film and not as borderline documentarian as Hittman’s, Happening balances the real and the poetic. The minimalist but effective score by Evgueni Galperine and Sacha Galperine consists of a few piano notes, striking in a singular fashion at a well-placed moment. The production design and costumes never call attention to themselves, while the framing and desaturated colors do not appear intentionally stripped down for a faux realistic effect. Diwan’s approach inhabits an in-between stylistic space that feels authentic without resorting to docudrama.

Above all, Diwan does not look away. She holds long takes with implied details whose uncomfortable and painful reality registers on Anne’s face in several abortion attempts. Mouglalis’ character uses a “wand” technique, warning Anne that her apartment’s walls are thin, so “Not a sound, or I’ll stop.” The blocking in these scenes once again places the camera over Anne’s shoulder, looking down to see details that make us squirm, look away, or nearly faint (my wife covered her mouth and confessed to nearly vomiting). Even so, little is shown. Diwan leaves everything to our imagination. These scenes prove visceral and unpleasant in their allusive power, but had Anne been able to see a doctor or take a pill, she might have avoided such discomfort. When the moment finally comes, Diwan repeats a tactic employed by Mungiu, offering viewers a momentary glimpse of the outcome. Where Happening differs from 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, mainly due to their respective national situations, is that Anne receives a happy(ish) ending. She will not resent a child who curtailed her potential, and she can fully realize herself without being constrained by sociopolitical obligations. In the end, she has her freedom—granted only because a male doctor chooses to label her case a “miscarriage,” whereas the alternative would have made her a criminal—and that’s a rarity for dramas about abortion. If the film’s ending can be called happy, Anne’s world is no less confining.

Above all, Diwan does not look away. She holds long takes with implied details whose uncomfortable and painful reality registers on Anne’s face in several abortion attempts. Mouglalis’ character uses a “wand” technique, warning Anne that her apartment’s walls are thin, so “Not a sound, or I’ll stop.” The blocking in these scenes once again places the camera over Anne’s shoulder, looking down to see details that make us squirm, look away, or nearly faint (my wife covered her mouth and confessed to nearly vomiting). Even so, little is shown. Diwan leaves everything to our imagination. These scenes prove visceral and unpleasant in their allusive power, but had Anne been able to see a doctor or take a pill, she might have avoided such discomfort. When the moment finally comes, Diwan repeats a tactic employed by Mungiu, offering viewers a momentary glimpse of the outcome. Where Happening differs from 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, mainly due to their respective national situations, is that Anne receives a happy(ish) ending. She will not resent a child who curtailed her potential, and she can fully realize herself without being constrained by sociopolitical obligations. In the end, she has her freedom—granted only because a male doctor chooses to label her case a “miscarriage,” whereas the alternative would have made her a criminal—and that’s a rarity for dramas about abortion. If the film’s ending can be called happy, Anne’s world is no less confining.

By some twisted circumstance, Happening arrives in theaters around the same time as leaked documents indicating the US Supreme Court will likely overturn Roe v. Wade. Watching the film inside a darkened theater, when outside thousands gather in protest around the country, results in a chilling experience. It’s not just that Diwan conveys the physical reality of Anne’s attempts with confronting visual and aural detail; it’s that she deploys mise-en-scène that boxes Anne inside a constrained world. Her story becomes both a page from history and a potential future for an untold number of less privileged women than Anne who may find themselves with no choice but to commit an act that could land them in jail or worse—suffering and possibly death from an unsafe procedure. The parallels enhance Happening for its modern-day significance in the USA, but they also further the veracity of Diwan’s filmmaking, thus heightening the dramatic result to distressing extremes. This is a remarkably confident film whose title tells us what was happening and could soon happen again. And while the subject feels urgent for the moment given its extratextuality, the film weighs Anne’s personal toll of an unwanted pregnancy against her personal freedoms and bodily autonomy—the right to complete her education, pursue a career, explore her desires, and have children when she’s ready—all through a profoundly human case.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review