Reader's Choice

Hannibal

By Brian Eggert |

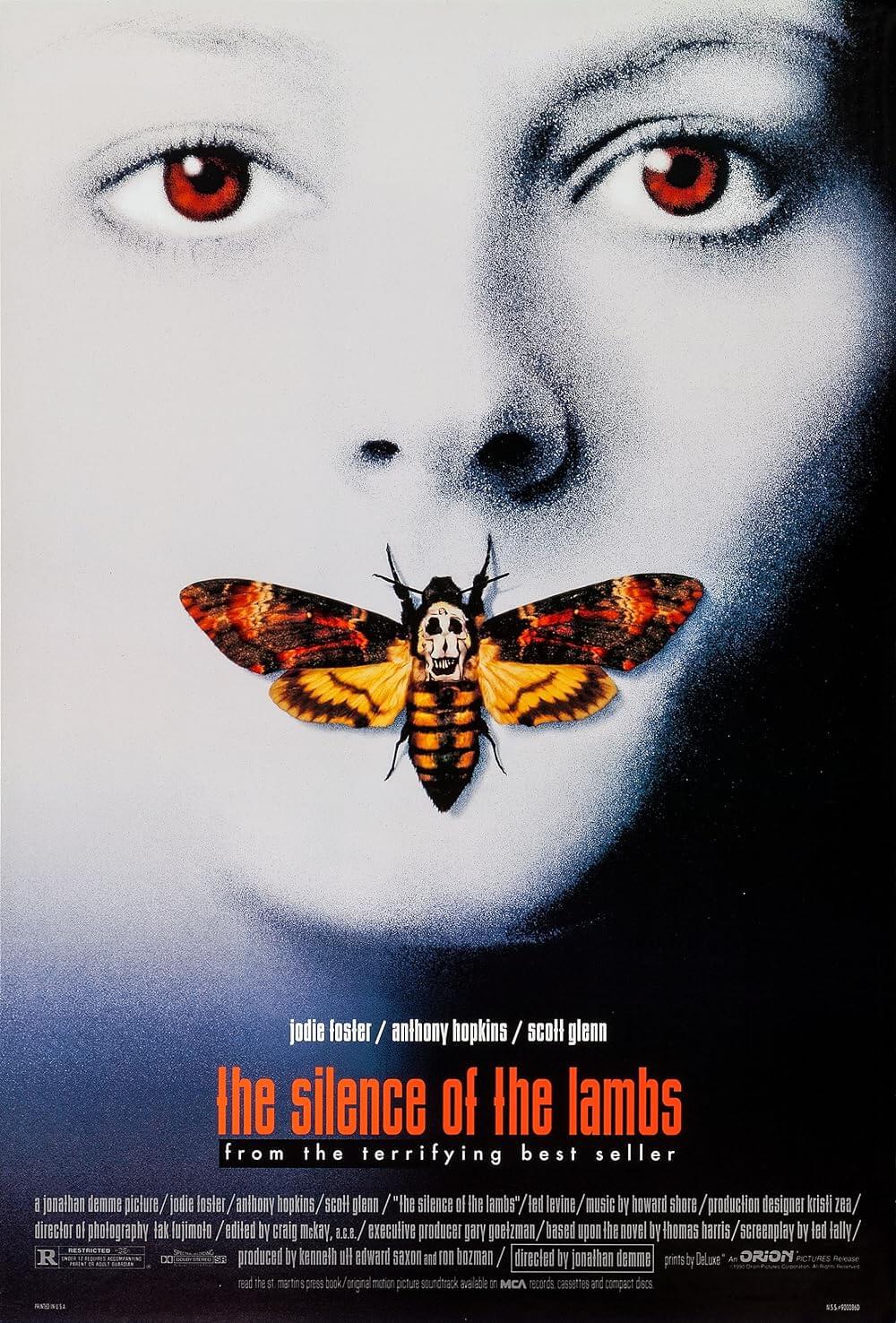

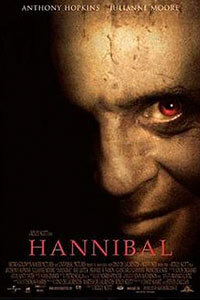

Hollywood couldn’t resist making a sequel to The Silence of the Lambs. After the 1991 film outperformed all box-office expectations and earned five Academy Awards, the opportunity cost of not making a sequel meant leaving hundreds of millions of dollars on the table. And so, the author Thomas Harris began to write the follow-up, propelled not by a story he needed to tell but by the promise of guaranteed book sales, not to mention an inevitable $10 million paycheck for the screen rights. Producer Dino De Laurentiis cut that check, despite the material’s mild resemblance to its predecessor. Jonathan Demme, director of The Silence of the Lambs, turned down the offer to helm the sequel, titled Hannibal, after taking issue with where Harris took the characters. Screenwriter Ted Tally, too, declined to adapt the book, placing the script in the hands of David Mamet, followed by an extensive rewrite by Steve Zaillian at the behest of Jodie Foster. But even after the rewrite, Foster turned down the offer to play Clarice Starling again, leaving the role to a capable replacement, Julianne Moore. Besides Anthony Hopkins, Hannibal Lecter himself, the only talent to return was Frankie Faison, who played Lecter’s kindly asylum guard, Barney. Harris’ book sold millions of copies, and the screen version earned over $350 million worldwide.

If the financial success of Hannibal hardly seems relevant to a discussion of the film, tell that to those involved, most of whom demanded a significant payday for their work in an obvious cash grab. The budget was a whopping $85 million; a decade earlier, Silence cost about $20 million, which is around how much Hopkins accepted to reprise his role. It didn’t matter whether the material did justice to the beloved characters or turned out to be, as Roger Ebert described it, “a carnival geek show elevated in the direction of art.” All that mattered was that Hopkins’ face would appear on the poster, and audiences would receive another dose of macabre situations, preferably involving cannibalism. Ridley Scott’s presence behind the camera, fresh off his Oscar-winning blockbuster Gladiator (2000), only helped the commercial prospects. But Silence had done such a thorough job of saturating 1990s pop-culture that regardless of whether Foster, Demme, or anyone else behind the camera refused to be involved, as long as Hopkins showed up, viewers would too.

To be sure, in the ten years since Hannibal’s predecessor debuted, the film had become a pop-culture landmark, inspiring parodies from an amusing reference by Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy (1996) to the not-so-amusing spoof with 1994’s The Silence of the Hams (starring Dom DeLuise as Dr. Animal Cannibal Pizza and Billy Zane as Jo Dee Fostar). The jokes and references go on and on, but viewers craved the real thing. Hannibal is not the real thing. Here’s a sequel that feels like no one involved understood what made Silence a great film. Rather than try to emulate Demme’s approach—a thriller told from the perspective of a woman, without flashy visuals, and only subtle variations on classical themes—Hannibal is a reflection of how the serial killer genre had changed in the time since Silence’s release. It had become dependent on gory slayings and flashy aesthetics, and each new entry tried to outdo the last in these departments until finally, the genre turned into torture porn with 2004’s Saw. By the time Hannibal Lecter returned to the screen, he would have to do some major bloodletting to keep the audience’s attention.

The problems with Hannibal start almost immediately with the title sequence—a dizzying barrage of black-and-white surveillance footage in Florence, interrupted by the occasional frame of gory crime scene imagery or a crow eating some fleshy morsel. The jarring cuts and high-speed footage mark a clear attempt to capture the titles of David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), except the sequence culminates with an absurd sight: a vague portrait of Hannibal’s face visualized with a flock of CGI pigeons that disperse in an empty square. The titles imply that Hannibal Lecter could be anywhere in the broadest possible terms. From these almost laughable titles to the high-toned score by Hans Zimmer to the frequent uses of slow-motion by cinematographer John Mathieson, Scott seems to liken Hannibal to an opera—and sure enough, Patrick Cassidy’s Vide Core Meum plays a role in the film, as does its source, Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nova. Highbrow references though they may be, they don’t distract (not enough, anyway) from the sequel’s blend of overreaching self-importance and shallow outcome.

The problems with Hannibal start almost immediately with the title sequence—a dizzying barrage of black-and-white surveillance footage in Florence, interrupted by the occasional frame of gory crime scene imagery or a crow eating some fleshy morsel. The jarring cuts and high-speed footage mark a clear attempt to capture the titles of David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), except the sequence culminates with an absurd sight: a vague portrait of Hannibal’s face visualized with a flock of CGI pigeons that disperse in an empty square. The titles imply that Hannibal Lecter could be anywhere in the broadest possible terms. From these almost laughable titles to the high-toned score by Hans Zimmer to the frequent uses of slow-motion by cinematographer John Mathieson, Scott seems to liken Hannibal to an opera—and sure enough, Patrick Cassidy’s Vide Core Meum plays a role in the film, as does its source, Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nova. Highbrow references though they may be, they don’t distract (not enough, anyway) from the sequel’s blend of overreaching self-importance and shallow outcome.

The story opens with Clarice Starling now a seasoned, no-nonsense FBI agent. When she’s deemed responsible for a drug bust that goes wrong, she’s assigned to a high-profile manhunt of Hannibal Lecter designed to improve her reputation in the public eye. The newfound interest in the still-missing Lecter is implanted by Mason Verger (Gary Oldman, under some incredible practical effects), a wealthy child molester with political connections. Verger survived Lecter’s wrath years earlier, after he was assigned to Dr. Lecter for therapy. The prescription: Lecter convinced Verger to slice away his face and feed the chunks to dogs. Now he’s a grim sight, all scar tissue and peeled-away eyelids. Anyway, the obsessed Verger dangles Clarice like bait, compelling Lecter to write her a letter from his current location in Florence, Italy, where he operates under a false name as an art historian. There, a detective named Pazzi (Giancarlo Giannini) spots Lecter and, hoping to keep up with the expensive lifestyle to which his younger wife (Francesca Neri) is accustomed, risks contacting Verger’s people for the $3 million reward for information leading to Lecter’s whereabouts.

From the outset, Hannibal feels impersonal. Whereas Demme placed the viewer in Clarice’s subjectivity, Scott prefers not to identify with any single character. This version of Clarice has a hardened shell, and her internal life seems to have been replaced by memories of her interactions with Lecter, used mostly as callbacks to Silence. Lecter’s sinister presence is like watching a deadly predator who also utters kitschy lines like “Okee dokee” and refers to packed bags as being “heavy as bodies” in front of Pazzi. It’s as though he wants to get caught. There’s an almost camp quality to Lecter this time around, as though it’s only taken two films for him to make Freddy Krueger’s journey from a frightening boogeyman in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) to a pseudo-Looney Tune in Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1989). Despite the character’s horrible crimes, Scott, following Harris’ lead, positions Lecter as an antihero against Verger and the American authorities, represented here by a contemptible and chauvinist Justice Department official, Paul Krendler (Ray Liotta). Lecter killing these unsavory types becomes a type of “public service,” we learn, suggesting our friendly neighborhood cannibal is doing us a favor. Isn’t he swell?

While Clarice remains on the sidelines, pouring over old crime scene photos and audiotapes of Lecter in her basement office, Lecter makes mincemeat out of everyone who attempts to apprehend him. We almost feel sorry for Pazzi, whom Lecter toys with and insults before disemboweling and hanging him like an unfortunate ancestor. Verger gets his just desserts when his plan to feed Lecter to flesh-eating pigs backfires in an admittedly nasty, memorable sequence. Krendler receives his comeuppance, too, when Lecter drugs him and feeds him a portion of his own brain. It’s all meant to be deliciously lurid, but it feels rather tasteless and shallow. The gory details of The Silence of the Lambs and Buffalo Bill’s flesh couture at least bore some symbolic parallels to Clarice’s transformation into a graduated agent no longer shaped by her past. Here, the banal eating motif caters to an audience wild about Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter, leaving beloved characters like Clarice tangled in the viscera.

While Clarice remains on the sidelines, pouring over old crime scene photos and audiotapes of Lecter in her basement office, Lecter makes mincemeat out of everyone who attempts to apprehend him. We almost feel sorry for Pazzi, whom Lecter toys with and insults before disemboweling and hanging him like an unfortunate ancestor. Verger gets his just desserts when his plan to feed Lecter to flesh-eating pigs backfires in an admittedly nasty, memorable sequence. Krendler receives his comeuppance, too, when Lecter drugs him and feeds him a portion of his own brain. It’s all meant to be deliciously lurid, but it feels rather tasteless and shallow. The gory details of The Silence of the Lambs and Buffalo Bill’s flesh couture at least bore some symbolic parallels to Clarice’s transformation into a graduated agent no longer shaped by her past. Here, the banal eating motif caters to an audience wild about Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter, leaving beloved characters like Clarice tangled in the viscera.

Scott’s production at least had the good sense to avoid Harris’ original ending, which finds Clarice and Hannibal running off together as lovers. Instead, we’re left with the director’s penchant for heavy-handed slow-motion sequences and grandiose camerawork that captures the beauty of Florence or Verger’s massive estate. Just as the use of unnecessary visual flourishes, the script lacks any depth, relying on our established fondness for Clarice and Hannibal to compel our interest. Except, these people don’t look like the Clarice and Hannibal we know; they’re strangers, and the script isn’t interested in investigating their lives. Even so, Scott captures the scenes of violence in memorable ways, including the tense drug bust opening that looks like something orchestrated by his late brother Tony. Ever the visualist, he allows himself to get wrapped up in the surfaces of things, not the people who inhabit these spaces, making the whole sequel feel superficial, complete with multiple nods to Gucci products (look for Scott’s biopic, House of Gucci, in late 2021).

Indeed, the film never elevates itself from a product. It’s shot and constructed like a commercial for itself—blatantly inspired by its money-making potential as opposed to any desire to outperform, augment, or even repeat the earlier film’s appeal. Hopkins turns up the hamminess, as though his entire performance is rooted in the same instinct that inspired him to slither after his famous Chianti speech in Silence. This makes Lecter little more than a shadow of his intimidating self. He’s too busy cracking wise and earning our sympathy against a cadre of bad guys to be scary. Moore fares somewhat better, suggesting Clarice has worked through her psychological hangups, but the character was not written with an inner life. What matters in Hannibal is that Lecter accumulates a body count and once more escapes with his freedom, spoon-feeding viewers the ghastly situations they were hungry for, with none of the psychological complexity of Silence. Along with Scott’s visually confident if misapplied direction, it’s all very serviceable and watchable while also being devoid of any substance and unworthy of prolonged thought.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review