Reader's Choice

Halloween H20: 20 Years Later

By Brian Eggert |

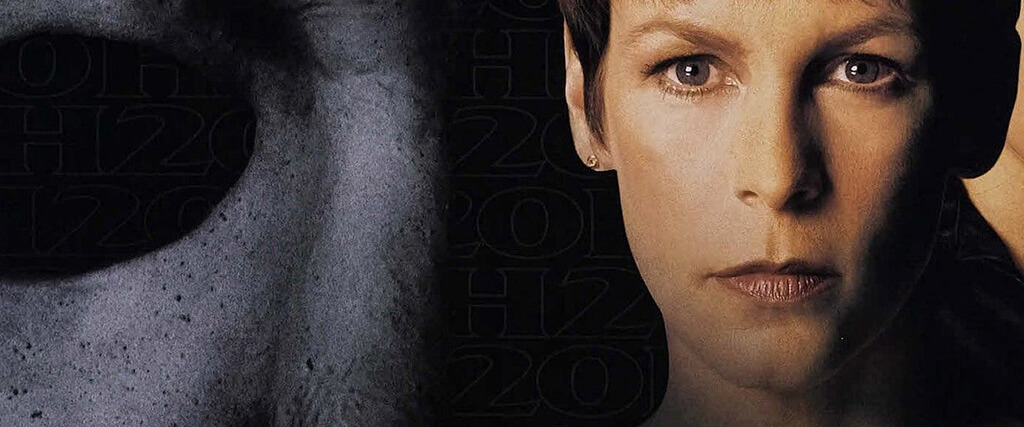

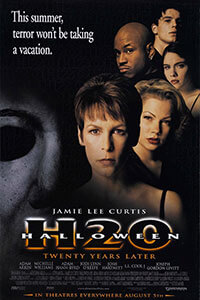

The repetitious title says it all, twice. Translated, Halloween H20: 20 Years Later means “Halloween Halloween 20: 20 Years Later.” That sort of stuttering uncertainty about itself carries through the 1998 release, here on out reduced to H20—a shortened version of the title that only brings to mind water, confusingly enough. Even if you can get over the absurd label (which could have only been developed by an overstimulated Hollywood promotional department in the 1990s), the movie does what the Halloween sequels have been trying to do since Halloween II hit theaters in 1981: recapture what worked about the 1978 original. This is evident from the initial sequence that finds Marion Chambers (Nancy Stephens), the nurse who assisted the late Dr. Loomis, still in her same old-fashioned nursing outfit from the first film. After apparently avoiding promotions or wardrobe changes for the last 20 years, Chambers, who took care of Loomis in his final days and presides over his records, finds herself murdered by Michael Myers. The masked killer has returned to acquire the secret location of his sister, Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), and carry out the murder he had planned two decades earlier.

Long before David Gordon Green retconned the franchise and made two sequels to John Carpenter’s Halloween for Blumhouse, Miramax’s genre division Dimension Films did it first. After the success of Scream (1996) and its 1997 sequel, slasher movies had made a comeback in the mid-’90s, largely thanks to screenwriter Kevin Williamson. His one-two punch of Scream and I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) led to several more of Williamson’s self-aware horror movies, such as The Faculty (1998) and Cursed (2005). This boom led to a contingent of copycats, including Urban Legend (1998) and Cherry Falls (2000). And while Williamson’s onscreen credit is limited to executive producer of H20, he doctored the screenplay by Robert Zappia and Matt Greenberg for Dimension, which had been in the Michael Myers business since distributing Halloween 6: The Curse of Michael Myers in 1995. The result oozes with Williamson’s interest in teendom and horror movie references, but it lacks well-developed characters and genuine thrills.

H20 has the quality of fan fiction, as many belated Hollywood sequels do. Take Michael Myers’ iconic mask—the painted-white William Shatner mask that looks like a disturbingly blank slate. The production, directed by Steve Miner, best known for helming the first two sequels in the Friday the 13th series, renders a couple of different looks for Michael depending on the scene. One doesn’t-look-quite-right mask appears oddly highlighted with black accent marks around the cheekbones and eyebrows. But most of the movie, Michael looks like some guy in a mask—someone dressed up in a Michael Myers costume purchased at Halloween Express. The larger eye holes aren’t the black, vacant circles seen in the original. Instead, the viewer can see Michael’s eyes behind the mask. The hair has also changed. The original mask had combed-back hair; the mask’s hair in H20 looks like Michael went for a spiky look popular in the 1990s (it’s a wonder he didn’t have frosted tips). The inconsistent effect suggests the filmmakers were trying to figure out Michael’s look from one day to the next. The result is unintentionally funny and, perhaps worst of all, not scary.

Michael’s appearance raises many questions—and not just about his physical appearance. In a similar retconned approach to Green’s later movies, H20 ignores the existence of the four series entries between 1982 and 1995, presenting itself as a sequel to Halloween II. So the question remains: What has Michael been doing for the last 20 years? (Roger Ebert’s jokey review at the time of the movie’s release suggested he was working in the fast-food industry, earning top marks for chopping onions.) The screenplay never offers a satisfying answer for how he supported himself and why, after so many years, he resolved to return on the 20th anniversary of his attack on Laurie. Why does he wear the same jumpsuit and not a new outfit? Why Halloween, besides the obvious anniversary angle? Michael’s motivations seem distractingly obscure without Loomis around to fanatically articulate their quality of sheer evil and almost mythological dread.

Michael’s appearance raises many questions—and not just about his physical appearance. In a similar retconned approach to Green’s later movies, H20 ignores the existence of the four series entries between 1982 and 1995, presenting itself as a sequel to Halloween II. So the question remains: What has Michael been doing for the last 20 years? (Roger Ebert’s jokey review at the time of the movie’s release suggested he was working in the fast-food industry, earning top marks for chopping onions.) The screenplay never offers a satisfying answer for how he supported himself and why, after so many years, he resolved to return on the 20th anniversary of his attack on Laurie. Why does he wear the same jumpsuit and not a new outfit? Why Halloween, besides the obvious anniversary angle? Michael’s motivations seem distractingly obscure without Loomis around to fanatically articulate their quality of sheer evil and almost mythological dread.

The screenplay makes odd, occasionally baffling choices. Consider the scene where a mother and her young girl stop at a rest area, driving a rusty old jalopy from the 1940s. Why does she have this car? Is she taking it to the junkyard? For a well-dressed mother and her child, it’s a distracting and unexplained detail. But conveniently enough, Michael has stopped at the rest area as well. So he trades in the car he stole from Chambers for the woman’s rustbucket, which looks like the sort of vehicle only a serial killer would drive. Later, Michael drives the beater up to the gates of Hillcrest Academy, a private boarding school where Laurie, hiding under an assumed name, serves as headmistress. The school’s security guard, Ronny (LL Cool J), notices the strange vehicle and its unresponsive driver. So what does he do? He opens the gate to check it out, naturally. Ronny is an unfortunate character, the Black comic relief saddled with a silly subplot that involves him reading his amateur erotic fiction to his wife over the phone. A year after Scream 2 joked about Black stereotypes in slasher movies, Ronny is a step backward.

The narrative’s main thrust follows Laurie, now overprotective about her 17-year-old son John (Josh Hartnett, appearing in his first role), fearing that Michael might return and kill him. Much of the story involves the rebellious John trying to arrange a romantic night with his girlfriend Molly (Michelle Williams) and his horny teen friends Sarah and Charlie (Jodi Lyn O’Keefe, Adam Hann-Byrd), while the rest of the school takes a field trip. Unfortunately, the amount of screen time spent on John convincing Ronny to let them leave the school grounds, acquiring alcohol, and preparing a romantic nook in the school’s sub-basement feels disproportionate to the usual suspense of a Halloween movie. Clocking in at 86 minutes, H20 expends nearly two-thirds its runtime before Michael shows up at the school and starts causing trouble. Even when he does, the result doesn’t compel many thrills.

Miner seems more interested in crafting cheap jump-scares and setups with no payoff. Again and again, a loud jolt on the score accompanies a false scare. Or watch the scene where Charlie drops a corkscrew in the garbage disposal. He looks down and considers sticking his hand inside. Then he looks at the switch as though it might suddenly turn on by itself. He flips the switch if only to show the audience what might happen to his hand should his flesh meet with the metal. Then, after shutting it off, he reaches inside and pulls out the corkscrew without incident. A moment later, Michael attacks. If Miner were at all interested in giving audiences a cheap reward, he might’ve had Michael force Charlie’s hand down the disposal before flipping the switch. But alas, Michael instead plays some games involving a dumbwaiter and electricity.

Michael then proceeds to go after John and Molly, who are quick to evade the killer in smarter-than-average ways. It all leads to a moment borrowed from Jurassic Park (1993), when Alan Grant faces a velociraptor through a round door window. In H20, Laurie locks a door just in time to come face-to-face with Michael through the oculus—an image prominently featured in the trailer and marketing materials at the time. But given Michael’s strange appearance, it’s any wonder why Laurie doesn’t question his identity. “Who’s this guy?” she should’ve asked. At one point in the movie’s long development process, Zappia pitched the idea of a copycat killer. Wouldn’t that have been an unexpected twist? It would also explain why Michael looks so off compared to the earlier movies. Then again, Michael’s mask has never been consistent. Horror blogs have devoted countless words to the minute differences between the many masks throughout the Halloween franchise.

Michael then proceeds to go after John and Molly, who are quick to evade the killer in smarter-than-average ways. It all leads to a moment borrowed from Jurassic Park (1993), when Alan Grant faces a velociraptor through a round door window. In H20, Laurie locks a door just in time to come face-to-face with Michael through the oculus—an image prominently featured in the trailer and marketing materials at the time. But given Michael’s strange appearance, it’s any wonder why Laurie doesn’t question his identity. “Who’s this guy?” she should’ve asked. At one point in the movie’s long development process, Zappia pitched the idea of a copycat killer. Wouldn’t that have been an unexpected twist? It would also explain why Michael looks so off compared to the earlier movies. Then again, Michael’s mask has never been consistent. Horror blogs have devoted countless words to the minute differences between the many masks throughout the Halloween franchise.

If there’s anything inspired about H20, it’s the familiar thematic arc that compels Laurie throughout the film, underdeveloped though it is. Like Green’s Halloween in 2018, H20 finds Laurie scarred from her experience in 1978. But, instead of becoming a well-armed doomsday prepper, she has descended into “functional” alcoholism—casually downing glasses of Chardonnay or chilled vodka to keep from confronting her past. She also has nightmares about Michael Myers attacking the school, and her paranoia conjures more than one phantom appearance by the killer. The screenplay underscores this with a parallel between Laurie and her lesson to literature students about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and why Dr. Frankenstein must finally face the Monster he created—just as Laurie must face the monster in her life. It’s a classroom scene that cheaply replicates a scene from the original Halloween, but the eventual moment when Laurie decides to face Michael head-on with an axe results in a thematic “ah-ha” moment. Whatever goodwill H20 builds, it feels undone by the achingly stupid follow-up, Halloween: Resurrection (2002).

It’s also worth pointing out that Janet Leigh, Curtis’ mother, appears as Laurie’s assistant. Carpenter already had the idea of having these two scream queens together in 1980’s The Fog, but the conceit doesn’t feel tired here—even if H20 overdoes the winking inclusion. “If I could be maternal for a moment,” says Leigh’s character before addressing her real-life daughter. (And it’s probably just a coincidence that Leigh also says, “Everyone’s entitled to one good scare”—a line spoken in the 1978 film by the Sheriff, whose first name was Leigh.) H20 also features a couple of references to Psycho (1960), Alfred Hitchcock’s original slasher movie, in the unmissable Williamson-style homage. None of H20’s many references to Halloween and other horror fare add much, besides underscoring the extent to which this and other sequels have kept trying to recapture the superb original.

H20 earned plenty in box-office receipts for Dimension, and it might’ve introduced some in the teenage mainstream to Carpenter and Hitchcock’s slasher landmarks (so it can’t be all bad). Still, it feels like a cash grab for all involved—another in a long line of crass commercial opportunities with underwritten scripts and inessential story developments. Although it’s more watchable than most other Halloween sequels, remakes, and reboots—which have all tried to exploit the intellectual property, though they remain creatively uninspired—it’s only preferable by comparison (and that’s not saying much). 1990s nostalgists may feel taken by the youthful Hartnett and Williams, and slasher buffs will continue to defend the movie as something more than passable. But in the wake of everything that came after Carpenter’s version, H20 feels like another in the franchise’s many attempts to bank on the iconic original instead of using it as a launchpad for something creatively distinct.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, David L.! )

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review