Halloween

By Brian Eggert |

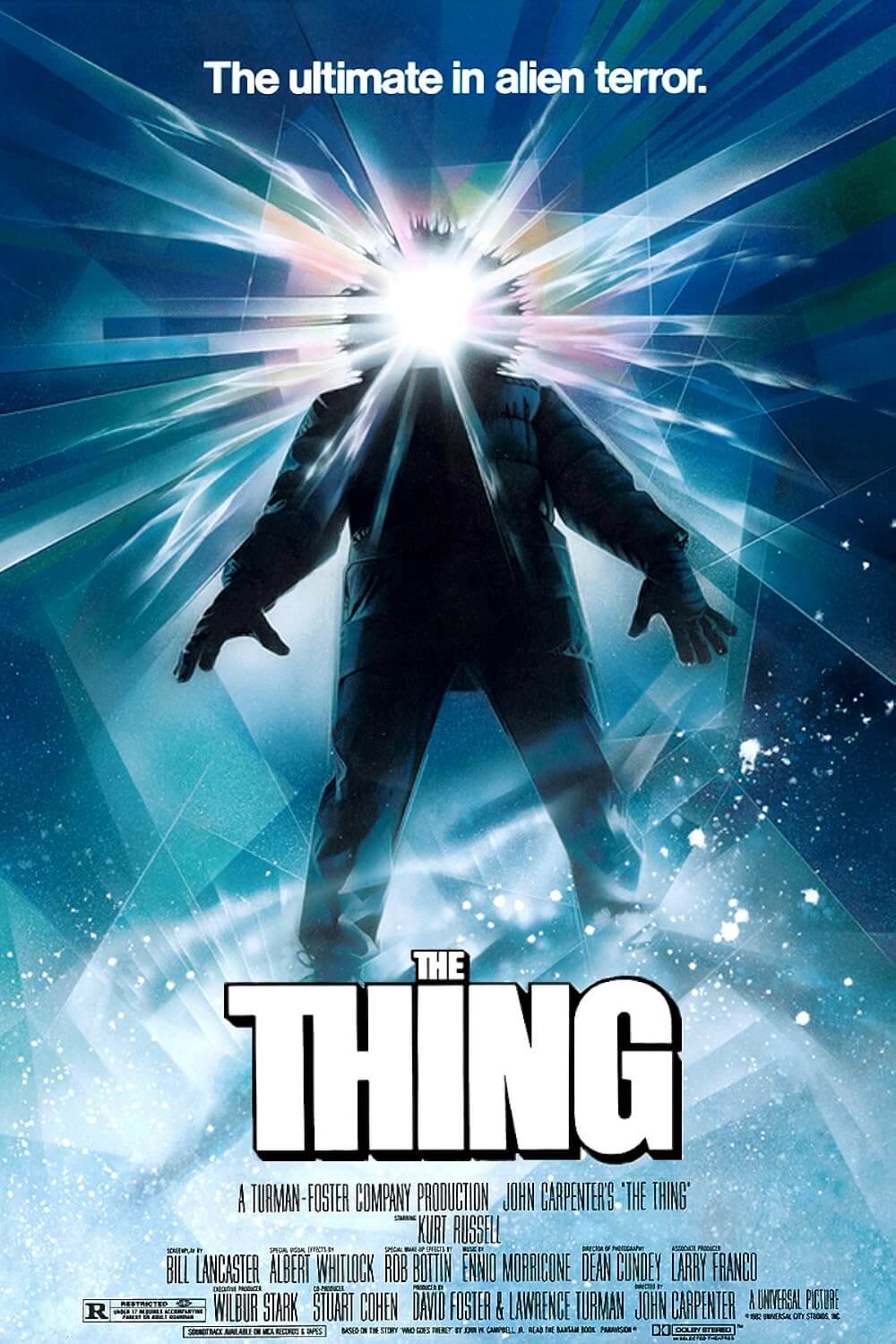

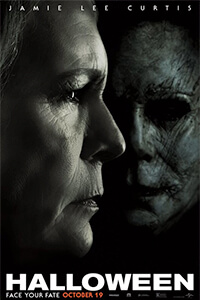

In the title sequence of director David Gordon Green’s Halloween, a pseudo-relaunch and sequel of the iconic horror franchise, we watch as a rotted pumpkin rematerializes, as though replaying time-lapse photography in reverse. A goopy, molded, and collapsed orange mass balloons into a freshly carved jack-o-lantern, resembling the one that appeared next to the opening credits of John Carpenter’s original Halloween in 1978. The new sequence can easily be seen as a metaphor for the movie’s ambitions to revive the franchise, which has changed ownership and authorship over the years, resulting in several downright awful sequels and a failed attempt to restart the series by Rob Zombie. The new iteration, produced by Blumhouse, Jason Blum’s house of horror responsible for recent franchises such as Insidious, Paranormal Activity, and The Purge, seeks to win the hearts of devoted fans by closely aligning itself with Carpenter’s original, as indicated by the symbolism of the opening titles. Jamie Lee Curtis returns to her career-launching role as Laurie Strode. Michael Myers even looks more like he did in 1978 when he was called The Shape—the name given to the character in Carpenter and Debra Hill’s script, denoting his status as a Boogeyman, an embodiment of unknowable evil—whereas, in the sequels, he never looked quite right. Along with a half-dozen visual nods to the original, Green’s movie is a labor of referential affection.

Retconning the mythology of Michael Myers, Laurie Strode, and the babysitter murders of Haddonfield, Illinois, Green’s script, co-written by his longtime collaborator Danny McBride, inserts itself between the original and everything that came afterward. This curious strategy seeks to delete unwanted or inconvenient story elements from the minds of viewers, similar to how Superman Returns (2006) pretended that neither Superman III or Superman IV: Quest for Peace happened. But the deletions made by Green and McBride are more significant. Their meta concept attempts to resituate the Michael Myers mythology to just after Carpenter’s first movie, before Halloween II (1981), which established that Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode was actually Michael’s sister, thus reducing his actions to an extended attempt to repeat the sororicide that he committed as a young boy. However, in the new Halloween, Green and McBride cannot overcome the cultural osmosis that has implanted the notion of Michael Myers and Laurie Strode as siblings. It’s as ingrained as Freddy Krueger being the “son of a hundred maniacs” or Jason Voorhees drowning in Crystal Lake. In their attempt to write around the escalating nonsensicality of the familial connections that emerged over seven direct sequels to Carpenter’s classic, they put the viewer into a muddled headspace, leaving it difficult to resituate everything we already know about the franchise.

The movie opens with two investigative journalists (Jefferson Hall, Rhian Rees) researching the Haddonfield murders of 1978 for their podcast. They’re essentially a continuity-establishing device and, through their expositional dialogue, they introduce Green and McBride’s new conception of the mythology between Michael and Laurie, the two primal forces at the center of the movie. They visit the hospital where Michael has been for 40 years following his capture that Halloween night in ’78, and they attempt to goad him out of his decades-long catatonia to no avail. It’s their last chance before the hospital transfers Michael to a more prison-like facility, warns his doctor, Dr. Ranbir Sartain (Haluk Bilginer)—”You’re the new Loomis,” it’s winkingly remarked later. Then the podcasters visit Laurie Strode, who has spent the last four decades writhing in paranoia and militant preparedness. Riddled with a history of mental problems and substance abuse, she lives on a secluded woodland compound loaded with booby traps, a gun range, and firearms galore. Curtis is clearly enjoying the new take on her first role, as her character is a basket case whose lifelong terror is not unjustified. Twice divorced, Laurie also has a now-grown daughter, Karen (Judy Greer), who resents the way her mother raised her in an environment of weapons and extreme self-defense. Karen tries to live a normal life with her good-humored husband Ray (Toby Huss) and their teenage daughter Allyson (Andi Matichak). Estranged from her grandmother, Allyson tries to rekindle a relationship with crazy grandma Laurie.

Inevitably, the bus that was to transfer Michael to another hospital crashes, on October 30 no less, setting the killer free to journey back to Haddonfield. As the bodies begin to pile up, Sheriff Hawkins (Will Patton) searches for Michael alongside Dr. Sartain, while Laurie frantically drives around town in her pickup truck on Halloween night, determined to kill the presence that has infested her life and mind—despite Michael being locked up for 40 years. This detail is significant, as other characters tell her to “get over it” throughout the movie before Michael’s arrival. After all, if the relationship between Michael and Laurie was limited to their limited interactions in 1978, as the new mythology suggests, it’s rather strange that Laurie has defined her life by this brief encounter. Why does she assume he will return, for instance, if she hasn’t spent the last four decades putting up with their many exchanges in the sequels? Unfortunately, the script doesn’t elaborate much on Laurie’s state beyond some vague allusions.

Meanwhile, almost with a sense of responsibility toward the slasher genre and its long-held tradition of dead teenagers, the movie diverts to Allyson and her group of friends. The couple Vicky (Virginia Gardner) and Dave (Miles Robbins) are introduced if only to be disposed of, but at least the little boy they’re babysitting (Jibrail Nantambu) has a few show-stealing funny lines—no doubt written by McBride in this uncharacteristically comical script. Elsewhere, even though several scenes establish Allyson’s new boyfriend, Cameron (Dylan Arnold), the character mysteriously disappears from the movie after it’s discovered at their school’s Halloween dance that he’s unfaithful. (A later reference to the dance being broken up because of Michael’s return to the frightened neighborhood suggests that, perhaps, a sequence in which Michael appropriately disposes of the cheating boyfriend was deleted.) In any case, after gleefully showcasing a few teen deaths, the movie concentrates on Laurie, who, after confirming Michael’s return, brings her reluctant family to her compound—a fortress designed to trap intruders of the knife-wielding, mask-wearing variety.

Green makes only slight attempts to replicate the look and feel of Carpenter’s original. This includes the movie’s basic color palette, and a few early scenes that show Michael out of focus in the background as someone in the foreground looks around, oblivious. The production recreates a convincing autumnal suburban landscape reminiscent of the original, with leaf-strewn sidewalks and overcast skies, while cinematographer Michael Simmonds uses a predominance of orange earth tones that signal the titular holiday. The score is quite good, with Carpenter, his son Cody Carpenter, and Daniel Davies providing an electronic reimagining of the original’s memorable, relentless notes (in recent years, the three musicians have contributed to Carpenter’s Lost Themes albums and toured together as a band). But rather than replicate Dean Cundey’s brilliant use of master shots and the wide rectangular frame from the original, Simmonds and Green employ disorienting close-ups of Michael’s tattered and filthy Halloween mask that reflects his age—he’s now in his sixties, as evidenced in off-kilter angles that barely glimpse the character’s thinning hair, leathered skin, and graying beard from behind. Green’s approach is also far gorier than Carpenter’s almost bloodless version: Michael strangles a child; he smashes the face of a gas station attendant to collect the teeth, which he uses to taunt another victim; he stabs several victims with his signature kitchen knife; and he stomps on a victim’s head, crushing it like a spoiled pumpkin beneath his foot. Though, one wonders how Michael retains such superhuman strength given that, according to Dr. Sartain, he’s been physically inert for the duration of his 40-year stay in the mental hospital, and thus should have experienced some muscle atrophy.

But perhaps this critical calculus of form isn’t fair to Green, who has made a visually compelling movie, in spite of the countless differences to what came before. Several of Green’s sequences prove frightening, such as a scary bit involving a lawn motion sensor or a tense few minutes that follow Laurie through her house, armed with a shotgun, methodically checking each room for Michael. To be sure, a persistent hunter-becomes-the-hunted theme emerges throughout the new Halloween, and Green finds not-so-subtle ways to suggest this role reversal. Take how Michael hides in a closet, just as Laurie hid in a closet in the original. Or take the scene when Michael and Laurie engage in a violent struggle on the second story of her home, and he throws her out of the window. She lands on the lawn below, identical to how Michael ended up in Carpenter’s Halloween. And as you might predict, when Michael peeks over the balcony to see if she’s still there, her cartoony imprint that remains on the grass is revealed with the same sharp stinger on the soundtrack to indicate the terror of her absence. Indeed, Green’s Halloween is filled with throwaway references to the earlier entries like this, such as the presence of sliced ham from Halloween II or the Silver Shamrock masks from Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), but they do little to enhance the story.

Although the new movie creates a renewed sense of dread over the long-unintimidating masked killer Michael Myers through its series of decidedly grisly murders, the sheer brutality of which is shocking, the material’s bizarrely retconned conceptualization, absurd twists, and overall fanfiction quality are self-consciously clever, distractingly so. Those unfamiliar with the previous movies will have an easier time settling into the experience, whereas, the movie caters itself to devoted fans, who, ironically, will undoubtedly take issue with many of the creative choices throughout. The movie functions well on a visceral level and in terms of craft, but situating its place in the Halloween continuity, or even our appreciation for the franchise’s legacy, remains more complex than a slasher remake or sequel should be. Nevertheless, Blumhouse’s new version is bound to spawn sequels of its own given the ambiguity of its finale, deploying another series of tired scenarios and comebacks for a new generation. The sad reality is, Green’s movie remains one of the best sequels in the franchise, which, given its mediocrity, isn’t saying much for everything that came after Carpenter’s original classic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review