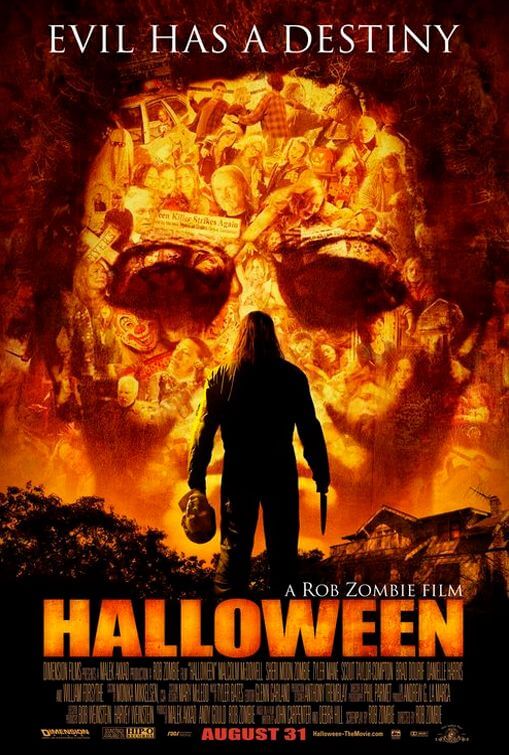

Halloween

By Brian Eggert |

Remakes have a poor reputation for treading on rather than paying homage to their originals. The idea behind them, I suppose, is to remarket a proven product to new audiences. I’ve always wondered why studios didn’t save some money and re-release the original classic film into theaters, just spending a reasonable, considerably lesser budget on advertising. Remarket the classic to audiences too young to have seen it upon its initial release. Save yourself the hassle of hiring some hack director to helm a poorly written movie that won’t be screened to critics because it’s dreadfully bad. That, or remake bad films with good concepts but that didn’t get it right the first time. Rob Zombie, director of House of 1,000 Corpses and The Devil’s Rejects is often said to be a promising horror director. Frankly, I don’t see it. His ultimate goal resides in replicating the visceral trailer park aesthetic of Tobe Hooper’s 1974 horror classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. His characters are usually written as cackling, backwoods psychopaths, constantly winking at the camera with their obscurity, every one of them grotesque beyond pity. In his work thus far, he has attempted to put a face on murderers, painting them like the sick and twisted portraits Hooper originally conceived of for his Texas cannibal family, along with several other titles, including Eaten Alive and The Funhouse.

With Zombie’s remake of John Carpenter’s original 1978 masterpiece Halloween, the writer-director demystifies everything Carpenter’s film made legendary in the most banal ways. He applies a Criminal Psychology 101 profile with a killer bred from a troubled home life, showing us Michael Myers’ backstory in an attempt to make him sympathetic, even a victim. But before I delve into the abyss that is Zombie’s film, I must acknowledge John Carpenter, an undisputed master of his time. That time may have passed, as Carpenter’s enthusiasm for making movies has dissipated over the years, but he was among the greatest filmmakers working in the horror genre in his prime. In 1978, Carpenter had one previous success (Assault on Precinct 13, which paid homage to Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo) before working on a script called “The Babysitter Murders” with friend and producer Debra Hill. After budgetary restraints demanded script revisions, Carpenter and Hill changed the story to focus on one night, and what better night for murder than Halloween? His characters named the killer Michael Myers, but when referenced in script direction, the masked killer was referred to as “The Shape”—as though Michael Myers was more an ethereal entity than a mortal figure. As Myers’ therapist Dr. Loomis suggests, he was pure evil and not worthy of a name.

The “slasher movie” (what Roger Ebert calls “dead teenager movies”) had barely been invented when Carpenter and Hill were writing Halloween. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was the first in 1960, trailed by 1974’s Black Christmas. With Halloween, Carpenter’s film established the “slasher movie” in pop culture, spawning numerous followers such as Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street. They all included a hero, typically a young woman, frequently a virgin, who would end up somehow stopping or simply surviving the killer, who was always a masked figure killing teens for one reason or another. “The Shape” did not have a reason, as opposed to Jason Voorhees or Freddy Kruger, who sought revenge for misdeeds done to them in their lives. What’s more, “The Shape” was not supernatural; rather, it was just mysterious. He did not show up in dreams or emerge from Crystal Lake; he was simply there, an unstoppable, faceless force. “The Shape” was nothingness, indescribable evil. It was unknowable, and so it remained shrouded in an arcane fear.

Zombie detracts from Carpenter’s “The Shape” and spends the first half of his remake removing any mysticism surrounding Michael Myers. His remake is like a lousy novelization, one where the writer invents his own story when trying to stay loyal to another. The result consists of one hour of Zombie’s obsession with the serial killer’s family and the other half with Laurie Strode—at times a shot-for-shot remake of Carpenter’s classic. We begin when Michael Myers is ten (played by child actor Daeg Faerch). His mother is a stripper, so he’s picked on at school for having a “whore” mom. That whore is played by Sheri Moon-Zombie, Rob Zombie’s wife. Young Michael wears a clown mask to hide his “ugliness.” He also kills animals and then photographs them (according to reports, Zombie’s script called for Michael to masturbate to the photographs of dead critters; luckily, those scenes were either cut or never filmed). His mother’s boyfriend, Ronnie White (William Forsythe), is wheelchair-bound, cusses out vulgarities, mocks babies for crying, and makes advances on the children. This performance is particularly grating, as White is the loud, obnoxious scab Zombie revels in writing. I kept wondering how long Zombie felt it would take us to figure out that Forsythe’s character is an asshole; apparently, a long time in the director’s mind, though viewers realize this fact after about 15 seconds.

Zombie detracts from Carpenter’s “The Shape” and spends the first half of his remake removing any mysticism surrounding Michael Myers. His remake is like a lousy novelization, one where the writer invents his own story when trying to stay loyal to another. The result consists of one hour of Zombie’s obsession with the serial killer’s family and the other half with Laurie Strode—at times a shot-for-shot remake of Carpenter’s classic. We begin when Michael Myers is ten (played by child actor Daeg Faerch). His mother is a stripper, so he’s picked on at school for having a “whore” mom. That whore is played by Sheri Moon-Zombie, Rob Zombie’s wife. Young Michael wears a clown mask to hide his “ugliness.” He also kills animals and then photographs them (according to reports, Zombie’s script called for Michael to masturbate to the photographs of dead critters; luckily, those scenes were either cut or never filmed). His mother’s boyfriend, Ronnie White (William Forsythe), is wheelchair-bound, cusses out vulgarities, mocks babies for crying, and makes advances on the children. This performance is particularly grating, as White is the loud, obnoxious scab Zombie revels in writing. I kept wondering how long Zombie felt it would take us to figure out that Forsythe’s character is an asshole; apparently, a long time in the director’s mind, though viewers realize this fact after about 15 seconds.

Zombie’s writing is so bad it’s almost laughable—but not in the so-bad-it’s-good campy way or the wonderfully abrasive chaos of Hooper’s style. His style is wretched and derivative. Nearly every line of dialogue includes swearing, not that my ears are sensitive to such language, but after 2 hours of constant profanity, it gets pretty old. He attempts to place blame on Michael’s family for raising a psychopath, which in turn would create sympathy for Michael, making him “not to blame” for his murderous reaction. Zombie’s version features Michael killing his entire family, save for his baby sister and mom. All this occurs just after Michael sits on his front steps with Nazareth’s “Love Hurts” drowning out the soundtrack, upset that he wasn’t taken trick or treating by his older sister Judith. It may be the most ridiculously, unintentionally funny moment in the film, or any film this year, or any film in any year for that matter.

Later, we see Michael under psychiatric care by Dr. Samuel Loomis (here played by Malcolm McDowell), who doesn’t help the boy, despite his efforts. Loomis repeatedly apologizes to Michael, stating that he’s failed his patient. With more blame deferred away from the killer, Michael is now not only the victim of bad parenting but of bad psychiatry. With every finger pointed in the wrong direction, Michael becomes less an instrument of terror and more just a disturbed freak. And when in adult Michael escapes captivity, Loomis seems to know he’s going home, likely to find his baby sister, now a teenager and living under the name Laurie Strode. Laurie was played in the original by first-timer Jamie-Lee Curtis, daughter of Janet Leigh, who herself was the horror vixen from Psycho and Carpenter’s The Fog. In Zombie’s film, Laurie is played by Scout Taylor-Compton, an actress who makes Laurie nothing more than your average “dead teenager.” Along with her friends Linda and Annie, Zombie reduces the three main teenage babysitter characters to personality-deficient victims. By contrast, Carpenter and Hill had enough know-how to make the three teens fleshed-out characters, however shallow they might be, each with distinct personalities.

Zombie is more concerned with clever casting than other, minor aspects, like a salient narrative. For example, Malcolm McDowell may have been an inspired choice for Loomis, but the character is a mess in Zombie’s movie. Being that Zombie’s Michael is a mere psychotic, a human killer bred from human dysfunction, it seems contrary to everything Zombie has told us thus far when Loomis begins ranting that Michael is evil. Or consider the role of Laurie’s friend Annie, for which Zombie cast actress Danielle Harris, better known as Jamie Lloyd, Laurie Strode’s daughter from the original Halloween movies 4 through 6. And there are appearances by Zombie’s group of principal players from House of 1,000 Corpses and The Devil’s Rejects, including Sig Haig, Tom Towles, and Ken Foree.

The most absurd bit of casting is pro-wrestler Tyler Mane as Michael Myers, as he makes Michael look, well, like a pro-wrestler, smashing through walls and punching police guards into a pulp like a ‘roid-crazed strongman. Zombie’s Michael Myers is the lovechild of Leatherface and Arnold Schwarzenegger, massively sized, obsessed with masks, and bizarrely muscle-bound. Both as a child and as an adult, Michael walks with his head down, his rock-and-roll hair draped over his face covering the “ugliness,” as he calls it (most heavy metal magazines feature Zombie in a similar pose, hair and all, curiously enough). In the mental institution, Michael fills his room with masks; at least one looks suspiciously like Leatherface’s mask from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: red with black around the eyes, nose, and mouth. Michael’s ongoing identity issues might fit the FBI profile that exists in Zombie’s head, but it’s cliché stuff at best.

Instead of explaining why Michael goes on this killing spree to find Laurie, Zombie’s solution is confused and brings about more questions than answers—such as why, if Michael is driven to murder by his family, does he murder so many other people? How does he know Laurie Strode is his little sister if her name was changed to protect her identity? Is Michael Myers some kind of private detective, or perhaps a psychic? I suppose the answers to these questions don’t matter, but since Zombie seems intent on exposing Carpenter’s original ambiguity, why leave any mystery at all? In Carpenter’s version, we could accept that there were no answers—he often worked with the faceless enemy, the horde approaching or emerging from the darkness to get you. Most of his movies are about just that (including Assault on Precinct 13, The Fog, The Thing, Christine, They Live, Prince of Darkness, In the Mouth of Madness, Ghosts of Mars, and even elements of Escape from New York). Carpenter’s Michael Myers was “The Boogie Man” of Tommy Doyle’s nightmares, unstoppable for reasons we could never know. His identity as “The Shape” sustained that mythology. By the time Zombie has Michael Myers confronting Laurie, we realize that Michael has killed everyone because he was trying to care for his baby sister. Aww, how sweet. He holds a picture up to her, one of Michael as a boy cradling the infant Laurie. It’s a moment that brought laughter to the theater during my screening. The only thing that could have made it more obvious and silly would have been to repeat “Love Hurts.”

John Carpenter proved back in 1982 with The Thing—his remake of Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World—that remakes can improve on previous material. But horror remakes have since been a depressing part of moviegoing, particularly for Carpenter fans. Hollywood has seen fit to make appalling new versions of Carpenter classics like Assault on Precinct 13, and The Fog, and rumors say that coming soon is Escape from New York. Is nothing sacred? Carpenter achieved archetypal status with bloodless shocker moments, strong actors, good writing, iconic music, and minimalist direction. Zombie removes all class and dignity from the original, pouring on blood for blood’s sake, drowning the movie in flashy camerawork, and detracting from the original Halloween in nearly every way, save for Myers’ mask and some plot elements in the second half. Worse, he steals relentlessly from another horror master, Tobe Hooper. Zombie’s movie leaves you disgusted by the writer-director’s apparent lack of ingenuity when rethinking Carpenter’s classic—a film that did not need a remake, and certainly not like this.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review