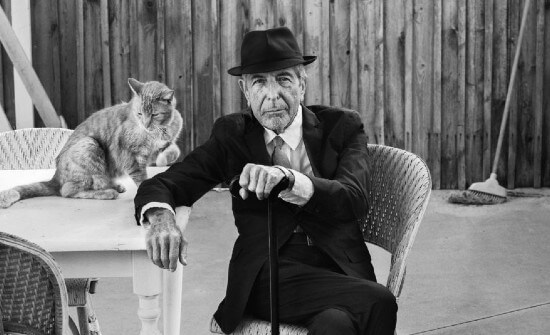

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song

By Brian Eggert |

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song details the continuous evolution and enduring legacy of Cohen’s anthem “Hallelujah.” The documentary by Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine looks at Cohen’s life through the lens of his 38-year-old song, which has taken a myriad of forms. In one of the film’s many talking-head interviews, Rolling Stone profiler and Cohen’s friend Larry “Ratso” Sloman recalls how the musician wrote around 180 verses and had alternate versions to each line, accumulated in a vast array of notebooks. The song started as a spiritual prayer and soon became a secular poem in Cohen’s hands, only to be seized upon by later musicians and repurposed into something else entirely. Jeff Buckley, Brandi Carlile, Bono, Eric Church, and countless contestants on televised singing competition shows have covered the song, each with distinct interpretations of its message and musicality. Cohen says it took him years to complete, but he never quite finished writing or revising it, and neither have other musicians. The doc considers the song’s origins and phenomenon throughout the singer’s life.

Inspired by a variety of religious sources—gospel music and the use of language at his synagogue—and blended with Cohen’s ponderous sensibilities, “Hallelujah” wields evocative imagery. Faith, sex, and despair combine into a melancholy ambiguity, followed by an outpouring of acceptance in the chorus. The song first appeared on Various Positions, Cohen’s 1984 album that struggled to find an audience. The head of Columbia Records at the time, Walter Yetnikoff, hated the album with conspicuous passion. He told Cohen, “Leonard, we know you’re great, but we don’t know if you’re any good.” In a decision that would become controversial, Columbia never released the album in the US, leaving Cohen to distribute it through independent and international labels. But the song never became popular until Bob Dylan and John Cale performed it, followed by hundreds of other artists. Even today, listening to the album version is underwhelming, whereas Cohen’s later recordings and live performances radiate with pain and spirituality.

Jeff Buckley’s rather edgeless and breathy version from the 1990s remains the most popular among many fans and musicians. He made it sound “like an angel was singing it,” says one commentator of the 1994 album called Grace. “It’s a great song. I wish I wrote it,” the singer admits in an interview before his death in 1997. From there, the song exploded. By the time the filmmakers of Shrek (2001) hired Rufus Wainright to perform it, with the “naughty bits” removed for the sake of children’s ears, the song had been softened and neutralized (they ended up putting Cale’s version with edited lyrics in the film, and Wainright’s version on the soundtrack). Even so, many of the later versions remove Cohen’s contrasts: his low, almost spoken-word manner of singing sounds beautifully incongruous with the song’s reverent tone. He sounds like a strung-out demon in a Neil Gaiman book, performing a hymnal after spending countless millennia in purgatory. The lyrics “She tied you to a kitchen chair, she broke your throne, and she cut your hair, and from your lips, she drew the Hallelujah” align with Cohen’s curious balance of carnality and spirituality that defined his persona.

Geller and Goldfine not only co-directed but also wrote, shot, and edited the film together using today’s popular scrapbook approach to documentaries. The film cuts amid archival footage, personal photos, vintage interviews, and new sit-downs with Cohen’s friends and collaborators. Occasionally, we hear a female voice (Goldine?) off-screen ask a question; otherwise, the filmmakers remove themselves from the chronological proceedings. Cohen came from a well-to-do family in Montreal, and unlike many in his profession, he didn’t hide his Jewishness. His search for identity became the ongoing theme in his life and music. “Unlocking the mysteries of life was his primary occupation,” says Sharon Robinson, Cohen’s regular collaborator. He often referenced his upbringing in Judaism but also mined Christian sources; he even had himself ordained as a Zen monk and spent extensive periods at a retreat meditating. Women became another source of therapy. Robinson notes that he “saw women as the path to some kind of righteousness or enlightenment,” which might be the most ridiculous excuse for womanizing ever conceived. Ratso claims Cohen’s existence was between “holiness and horniness.” That sounds more appropriate.

Geller and Goldfine not only co-directed but also wrote, shot, and edited the film together using today’s popular scrapbook approach to documentaries. The film cuts amid archival footage, personal photos, vintage interviews, and new sit-downs with Cohen’s friends and collaborators. Occasionally, we hear a female voice (Goldine?) off-screen ask a question; otherwise, the filmmakers remove themselves from the chronological proceedings. Cohen came from a well-to-do family in Montreal, and unlike many in his profession, he didn’t hide his Jewishness. His search for identity became the ongoing theme in his life and music. “Unlocking the mysteries of life was his primary occupation,” says Sharon Robinson, Cohen’s regular collaborator. He often referenced his upbringing in Judaism but also mined Christian sources; he even had himself ordained as a Zen monk and spent extensive periods at a retreat meditating. Women became another source of therapy. Robinson notes that he “saw women as the path to some kind of righteousness or enlightenment,” which might be the most ridiculous excuse for womanizing ever conceived. Ratso claims Cohen’s existence was between “holiness and horniness.” That sounds more appropriate.

When thinking about Cohen’s life, it would make a fascinating dramatic biopic because it doesn’t conform to the usual trajectory of many musicians’ lives. By comparison to the standard, there’s much more prayer and inwardness in Cohen, who was acutely aware of the suffering in the world and managed his disenchantment through spiritual outlets. The filmmakers weigh his existential search against the meaning of “Hallelujah,” which the singer doesn’t necessarily equate to a religious refrain. Biographical details about Cohen’s disastrous work with Phil Spector, his late-life business troubles with a duplicitous manager, and his influential presence on the soundtracks of Robert Alman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1994) barely get mentioned next to the investigation of the song’s rise to a “modern prayer.” Nevertheless, that sort of focus on the song’s ability to send crowds into a collective spirituality remains fascinating.

However, the doc overplays the titular song. It’s lovely music, of course. But as much as one loves the song, hearing its chorus repeated over and over for nearly two hours wears the viewer down to the point of frustration. In response to the endless covers and saturation of the music, Cohen tells one interviewer, “I think people oughta stop singing it for a while.” Ratso thinks he was kidding. But perhaps he wasn’t. Cohen might have recognized that the adaptations and commandeering of the lyrics and melody have sanded down Cohen’s original meaning. Many later artists would revise Cohen’s grim imagery and not-so-subtly eliminate his perspective from their decidedly Christian versions. For Cohen, the song was about feeling broken yet surrendering to the possibility of gaining some measure of self-understanding by whatever means possible. Fans of the song may not care about Cohen’s intentions and will likely savor Geller and Goldfine’s doc, which reveals how every artist surrenders their art upon its creation, for better or worse.

(Note: Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song opens in the Twin Cities on July 29, 2022.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review