Hail, Caesar!

By Brian Eggert |

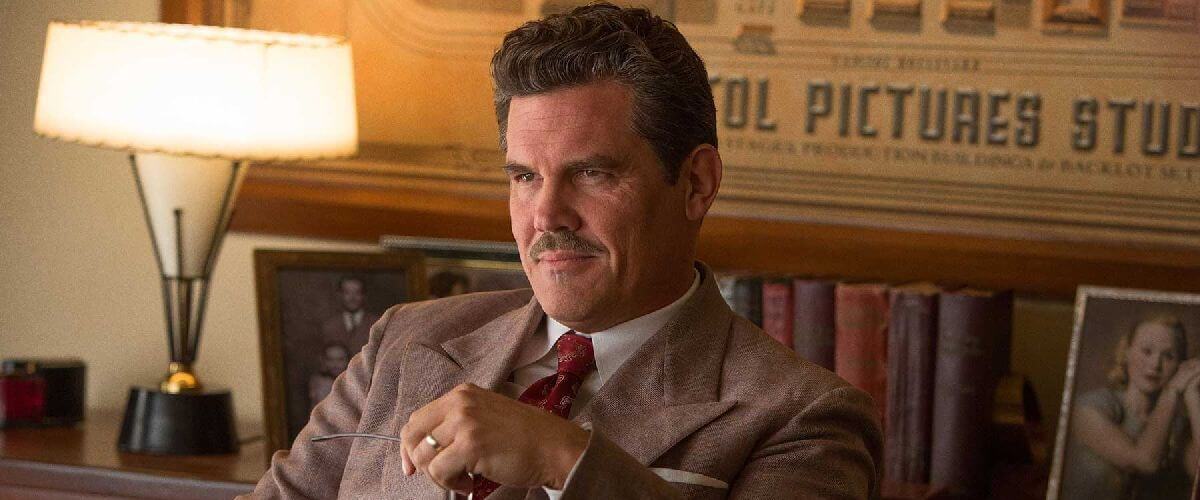

When John Turturro’s eponymous character first enters the offices of Capitol Pictures in Joel and Ethan Coen’s Barton Fink (1991), the New York playwright is subject to the fast-talking bombastitude of 1940s studio head Jack Lipnick. Fink’s gradual decline from his own writer’s block and the studio’s demand for less “fruity” pictures represent the Coens’ scathing view of Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age. The Coens’ Hail, Caesar!, set ten years later, features the same fictional studio with no less bombastitude. Although there’s no mention of where Fink or Lipnick ended up, the dream factory of Capitol Pictures seems to be running smoothly under the sharp eye of Josh Brolin’s long-suffering studio “fixer” Eddie Mannix. His thankless task of damage control involves keeping track of his stars and ensuring every production on the lot remains on schedule and under budget. Seemingly frivolous and touched with a hint of almost screwball comedy, Hail, Caesar! proves just as searching as many of the Coens’ other works. Tonally, it could be the lovechild of Burn After Reading, A Serious Man, and their aforementioned Hollywood tale.

Deceptively lighthearted, Hail, Caesar! balances some heavy themes, though not as elegantly as their more reflective efforts. Foremost, the Coens consider four distinct institutions onto which we cling and fill our lives with meaning: American culture’s reliance on escapist entertainment; defining oneself through their occupation of choice; religion as a way of shaping, if not commandeering one’s life; and our full devotion to any number of political philosophies, here represented by Marxism. Film, work, religion, politics—each are ideals propped up and held dear by their respective disciples in the film. And while not particularly critical of one specific method or another to fill one’s life, the film’s events and main character clearly side with the Coens’ own partiality toward film. Perhaps that’s why their protagonist Eddie Mannix is equated to Christ from a religious perspective, since he suffers for the sins of his studio and its talent; or by contrast Satan from the Marxist view, as Mannix remains a figurehead of a studio whose arguable sole purpose is to profit from moviegoers rather than supply its audience with a functional necessity.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The story follows Mannix, whose daily routine begins by confessing his sins to a priest at four-in-the-morning. Every day, Mannix oversees several of Capitol’s productions and answers only to an off-screen studio head. Frustrated directors. Prima donna actors. Technical and budgetary troubles. He’s pulled in every direction. Central to his workday is Capitol’s new prestige picture, called “Hail, Caesar!” no less. It’s an expensive period epic about the emergence of Christ as seen through the eyes of a Roman soldier, played by Capitol’s top star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney). Whitlock’s well-established boozing and philandering is spiced with vague mentions to a past scandal, all of which Mannix must keep out of the papers (here represented by the resident Hedda Hoppers, a pair of twin sister columnists, both played by Tilda Swinton). He moves from one potential disaster to another, keeps a cool head, and always finds a solution. Just as in Barton Fink, many of the Coens’ Hollywood characters have real-life counterparts. Mannix serves as an amalgamation of an MGM exec nicknamed “Eddie” Mannix, but also Howard Strickling, MGM’s head of publicity.

Like many Coen protagonists, things get increasingly terrible for Mannix. Joel Coen once described their standard writing process as dreaming up “horrible situations to put the characters through,” and Ethan explained they “make it worse” for effect. Mannix begins his day by trying to quit smoking. That’s stressful enough. He’s also been offered a job for the Lockheed Corporation on a prime salary and guaranteed ten-year contract; he’d never have to work again after ten years, but he’s unsure if he should take it. Along with the usual studio predicaments, Mannix also discovers that his top star, Whitlock, has disappeared from the lot. Soon he receives a ransom note, signed from “The Future”, asking for $100,000 in exchange for the actor. It’s yet another thing to keep out of the columns, but production on “Hail, Caesar!” has to halt without their movie star until Mannix can get its star back. Hail, Caesar! also contains an omnipotent narrator; actually, it’s the same narrator (Michael Gambon) as the film-within-the-film—an almighty British-accented voice that narrated on any number of religious epics from yesteryear. The voice follows the Christ-like Mannix on his punishing, selfless journey to protect Capitol Pictures and bring people the entertainment in which he believes.

Over the course of Mannix’s journey, the Coens often lose track of the plot to tangential scenes showcasing the humorous, and often absurd, behind-the-scenes filmmaking process. More than half of Hail, Caesar! involves scenes such as this, where the Coens get caught up in paying homage by recreating ‘50s-style sets and studio projects. Film buffs will appreciate the assorted nods to a cross-section of filmic archetypes from earlier cinema. There’s a beautiful Busby Berkeley musical number involving synchronized swimmers and a gassy Scarlett Johansson in a mermaid tail. Another sequence showcases a lowbrow Western star, Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich), shooting bad guys and performing horseback acrobatics. Hobie’s popularity with audiences earns him a miscast role in a sophisticated drama directed by Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes, channeling Laurence Olivier); unfortunately, Hobie isn’t known for more than his lasso skills, so real acting comes as a challenge. And let’s not forget about the hilariously homoerotic, Gene Kelly-esque dance sequence (to a song called “No Dames”) featuring a band of sailors—among them Channing Tatum, who gets a chance to show off his expert singing and dancing skills.

And while critics devoted to the notion of pure story may scoff at these sometimes superficial and whimsical asides, others will savor the joy and skill with which they were made. Production designer Jess Gonchor imagines, superbly details, and vividly colors a multitude of movie sets and memorable locations, such as the cliffhanging Malibu house owned by the wealthy Marxist behind Whitlock’s kidnapping. The Coens’ longtime cinematographer Roger Deakins captures each of these locations and sets in Hollywood light reminiscent of Golden Age productions; even the would-be real-life sky and backgrounds look like sets, quite intentionally so. Elsewhere, several big-name performers appear for a single scene. Jonah Hill appears as a “person for hire”—a studio employee who takes the fall when a celebrity is caught in a scandal. Frances McDormand plays a chain-smoking editor with fast hands. Alison Pill appears briefly as Mannix’s homemaker wife.

There are countless amusing moments in Hail, Caesar!, but like A Serious Man, the outward comic setup serves as a springboard for something far more existential. Finding the core of the film’s meaning requires the viewer to look beyond the occasional silliness onscreen. The Coens explore their rather big ideas with a biting sense of humor that may be lost on some, while cinephiles and those versed in even a slight knowledge of theology or Marxist theory will enjoy. Take when the Marxist kidnappers begin to sway Whitlock with their political and social views; Clooney’s enthusiasm and his character’s understanding of their point of view are hilarious (it’s the latest of four performances for the Coen brothers where Clooney plays a fool). Or there’s a riotous scene where Mannix tries to avoid offending anyone with the studio’s new religious epic by consulting a Jewish rabbi, a Catholic priest, a Protestant pastor, and an Eastern Orthodox clergyman for their reaction to the script. But they greet the material only with mild indifference. While all other institutions and belief systems incite an absurd level of devotion in Hail, Caesar!, the Coens and Mannix have made their choice clear by the end: it’s cinema that drives them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review