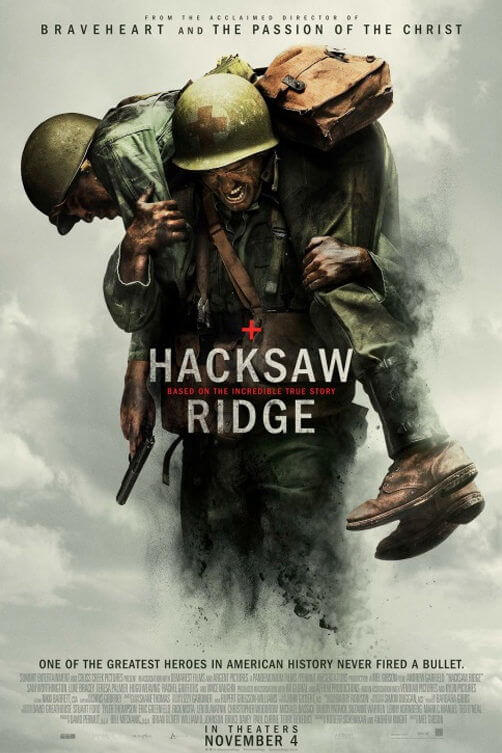

Hacksaw Ridge

By Brian Eggert |

If Americans are searching for real-life heroes today, they won’t find them amid the media’s coverage of racially charged police shootings and divisive election candidates. But a recent string of cinematic “docubusters” have told true stories of survivors and patriots with titles like Lone Survivor (2013), American Sniper (2014), and this year’s Deepwater Horizon or Sully. Each example tells a complicated tale in basic terms, eliminating any gray area in favor of simplicity and sanctification. At the end of each film, we see actual footage or photos of their respective figures in gestures of broad and unnuanced exaltation. Such films engage in hero-making for audiences prone to unabashed flag-waving or faith-based stories about Christ-like soldiers maintaining their convictions through impossible odds. And since moviegoers flock to films like this, it seems Americans are indeed desperate for heroes today.

Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge is among the best of this recent churn of based-on-a-true-story films. Written by Robert Schenkkan and Andrew Knight, it tells a classical kind of yarn that might have more in common with Howard Hawks’ Sergeant York (1941) if it wasn’t so gory. Gibson directs in the same high-intensity mode at which he delivered his visceral Braveheart (1995) and The Passion of the Christ (2003), wherein his protagonists fight for their beliefs until suffering for them in a punishing climax. Fortunately, the hero of Hacksaw Ridge makes out better than William Wallace or Jesus. Desmond Doss received the United States Congressional Medal of Honor in spite of being a conscientious objector. A Seventh-Day Adventist, Doss served as a medic in World War II and, though he never fired an army-issue rifle, he’s attributed with saving 75 soldiers on the field of battle.

The film opens with scenes of Doss’ upbringing in Lynchburg, Virginia, where he and his brother endure beatings by their father (Hugo Weaving), a World War I veteran suffering from alcoholism and survivor’s guilt, and alternate comforts from their mother (Rachel Griffiths). Andrew Garfield, who somehow maintains a boyishness at 33-years-old, plays Doss as a young man. Though in the middle of courting a local nurse (Theresa Palmer), Doss resolves to enlist following the attack on Pearl Harbor. He plans to serve as a medic, but his religious beliefs come into question by military officials when he refuses rifle training. His drill sergeant (Vince Vaughn, effective) and commanding officer (Sam Worthington) encourage him to quit, while Doss’ fellow soldiers accuse him of cowardice. Still, Doss remains unshakable in his resolve, a quality proved once he’s granted the chance to serve after avoiding a court martial.

Hacksaw Ridge takes its name from a 350-foot cliff, actually called the Maeda Escarpment, on the island of Okinawa, the setting of the film’s jarringly bloody second half. Gibson seems to revel in heated battle scenes, which explode onto the screen with copious amounts of viscera, entrails, maggot-ridden corpses, and other assorted carnage. Doss runs about this volatile setting, dragging or carrying men back to safety amid gunfire and detonating artillery. But many of the battle sequences lose sight of Doss in order to juxtapose his pacifism with a depiction of War-Is-Hell that rivals Saving Private Ryan in its veracity. In a way familiar to Gibson’s other directorial work, long sequences fetishize violence and death, while nameless American soldiers lose their lives and demonized Japanese soldiers represent nothing less than pure, inhuman evil. Even so, alongside cinematographer Simon Duggan and editor John Gilbert, Gibson makes his modest $40 million budget look like the production cost three times as much.

Like many of the docubuster titles mentioned above, Doss’ tale of heroism feels cleaned for mass consumption to a suspicious degree, complete with a heavy-handed score by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Consider a late scene where Doss, wounded, lies on a stretcher, while a computer-augmented camera movement catches him from a low angle in a heavenly light. Certainly, Doss’ convictions and heroism remain noble enough on their own without glorifying through blatantly religious imagery. Meanwhile, Doss’ troubled life after the war has been conveniently omitted, but the simplicity and nobility of the character remain true, as do many of his astounding feats accomplished on Okinawa. Just before the end credits, Gibson shows us interview footage with the actual Doss before his death in 2006, offering Doss’ own account of one of the film’s dramatized rescues. Seeing the real Desmond Doss speak may be a treat, but it removes the lasting effect of the filmic drama.

Although viewers may be quick to dismiss Hacksaw Ridge for its director’s past behavior of anti-Semitic and sexist remarks, Gibson has been sober for a decade and seems to have made peace with himself (as evidenced by his onscreen penance in Blood Father). However you may feel about the personal life of the man behind the camera, he’s an undeniably accomplished and talented filmmaker. Gibson has created an affecting story and orchestrates cinematic violence with impressive formal precision. But therein lies the problem, as Hacksaw Ridge seems at odds with itself, particularly during the chaotic and gruesome second half, as it tells a story about a brave pacifist while also satiating the filmmaker’s long-demonstrated bloodlust. A contradictory experience that remains commendable for its craft yet questionable for its inelegant thematic contrasts, Gibson’s film is full of troublesome contradictions, but it’s also extremely watchable.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review