Greenberg

By Brian Eggert |

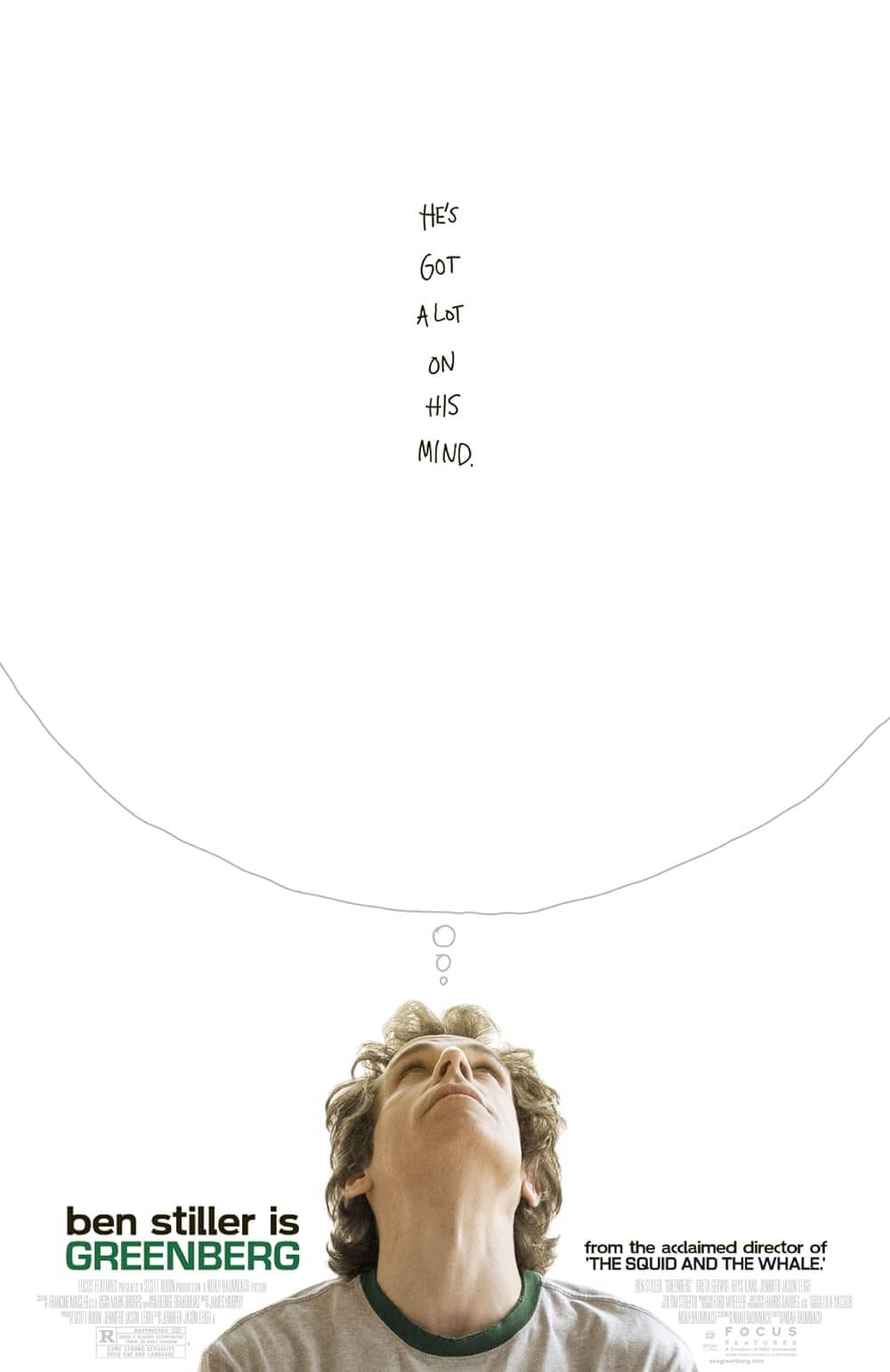

Ever since Ben Stiller was labeled the “neurotic guy” in retaliation for calling Josh Brolin and Richard Jenkins “a couple of gay guys” in David O. Russell’s hilarious Flirting with Disaster, the actor has played versions of the “neurotic guy” in countless roles that have formed his onscreen persona. He redefines his own stereotype in Noah Baumbach’s new film Greenberg, where his character’s neuroses aren’t the stuff of a wacky comedy character type, but rather, they supply the central flaw his character must overcome. This observant, clever, and at times painfully funny story showcases Stiller’s rarely tapped versatility as an actor, even if his character takes the entire length of the film to warm up to.

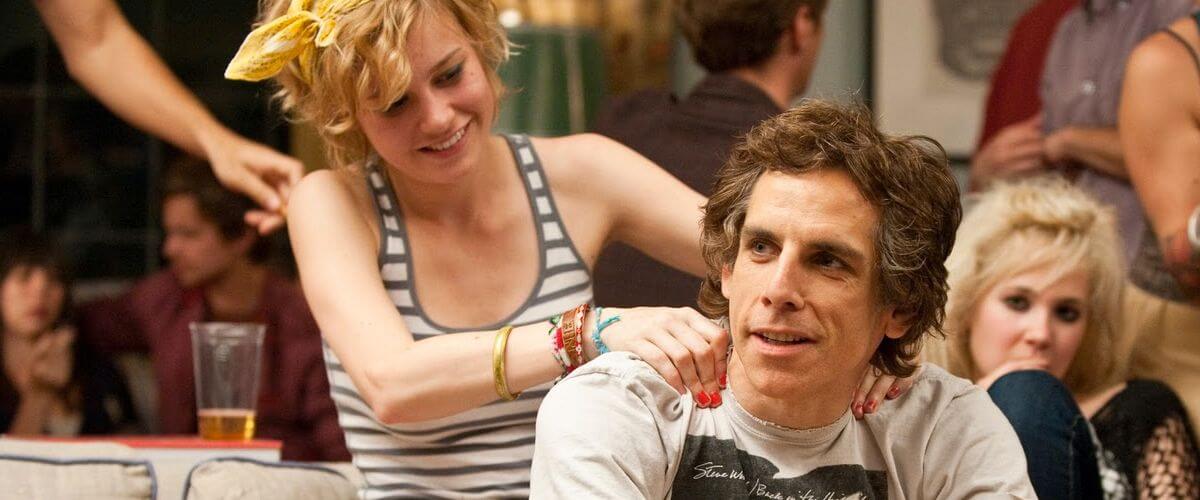

Baumbach, best known as one of the top progenitors of the 1990s indie film movement, and for his quirky, low-key dramas like The Squid and the Whale and Margot at the Wedding, leaves behind his typical New York surroundings for an uncommon West Coast story. In true Baumbach form, his protagonist is a failed, self-absorbed artist whose uncouth behavior has made him lonely and questioning his life. Stiller plays Roger Greenberg, an obsessive-compulsive would-be musician who has resolved to become a carpenter. After being released from a mental hospital, where he was recovering from a nervous breakdown, Greenberg stays in the home of his brother’s family in Los Angeles while they’re away on vacation. There, Greenberg bonds with the family’s German shepherd named Mahler and begins a casual affair with his brother’s personal assistant, the equally astray Florence (Greta Gerwig).

“I have to stop doing things just because they feel good,” Florence remarks, and perhaps she’s right. The character drifts in and out of casual sex relationships, which comes back to bite her later on, but with Greenberg, she wants to take it slow. Strange, considering his misanthropic attitude throughout the story. He writes angry letters to the mayor’s office and Starbucks, grieving about whatever comes to mind; he makes rude statements and cares not for social niceties; he’s not even sure that he likes the people he likes. Regardless, Florence sees something interesting in him between his insensitivity and boorish outbursts—maybe it’s that he’s content with doing nothing with his life. He seems to have no real friends, and even his “best friend” Ivan (Rhys Ifans) grows to truly despise him.

It’s easy to dismiss Greenberg as representative of typical Baumbach, as it’s filled with snobby characters that might only appeal to audiences attuned to Los Angeles and New York City temperaments. But the writer-director has certainly carved out a niche for himself, speaking to the erudite loafers that his characters reflect. Despite his somewhat limited range, Baumbach never fails to create ponderous works that have a way of sticking with you long after they’re over. Indeed, this critic left the theater indifferent, but then the film began to sink in. And now, after long consideration of the work as a whole, it’s easy to look upon it with admiration for its occasionally harsh potency and life-lesson insight.

This film, in particular, stands out as one of Baumbach’s best because of its use of risky characters. Stiller and Gerwig bring multiple dimensions to their roles, but at first, those dimensions are admittedly deplorable. Florence begins as a naïve slut, while Greenberg is nothing short of an impenetrable narcissist. Slowly, the script allows these actors to chisel away layer after layer until their characters’ tender centers open up in the finale. Stiller seems to have been building to a role like this for a number of years, interspersing offbeat titles like Your Friends and Neighbors with the standard Meet the Parents and Night at the Museumfare. Whereas Gerwig’s career as an indie favorite (see Baghead or Hannah Takes the Stairs) hopefully takes off after her performance here.

Though certainly not for general audiences, Baumbach’s brand of smart and darkly comic motion pictures has its crowd, and we appreciate what he does and how well he does it. He’s an adept and thoughtful filmmaker. Visually, he resists a produced look and instead glazes the frame with natural smog-laden light from Los Angeles. Along with avoiding heavy makeup on his actors and employing an intimate camera, he makes his audience feel like participants in an intimate drama. For those unfamiliar with his work, make note that he teamed with Wes Anderson to write the screenplays for The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and Fantastic Mr. Fox, and their styles mesh effortlessly. As his most challenging film to date, Greenberg should not be missed by Baumbach fans.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review