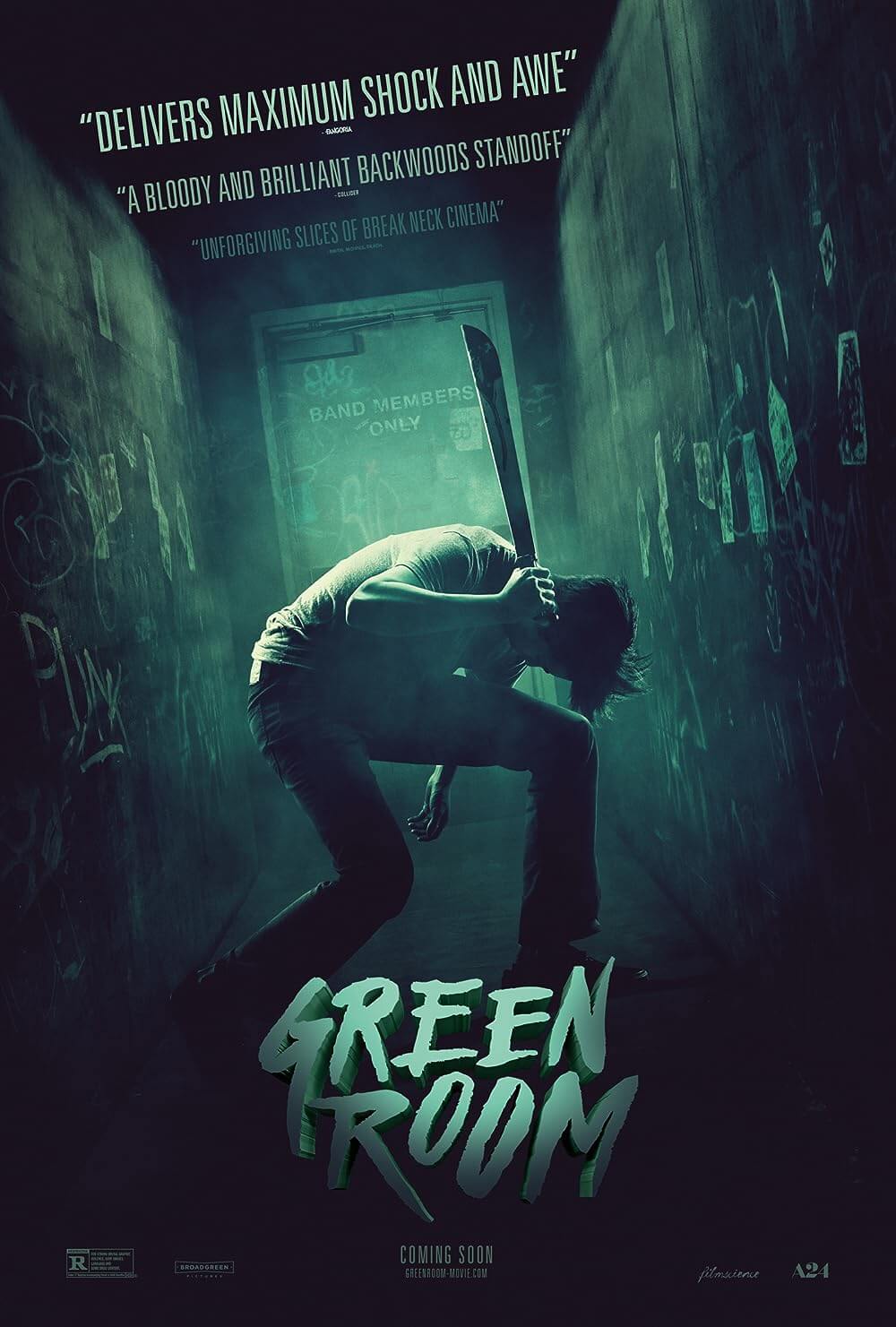

Green Room

By Brian Eggert |

Pitting a genuine hardcore punk bank against a gang of ruthless neo-Nazis in a film sounds like something you’d find while scrolling through the many rungs of drivel on Netflix. Put that idea in the hands of an artist-filmmaker like Jeremy Saulnier, whose slow-burner Blue Ruin was an essential thriller from 2014, and you get Green Room, an unrelenting siege of shocking violence and intractable characters. Marked by the same undercurrent of comic irony found in his previous release, Saulnier’s third feature (his debut was the extremely low-budgeted Murder Party, 2007) is efficient and tense as films get, leaving all unnecessary information off the screen. Green Room also boasts an incredible cast, no end of surprises in spite of what might seem like a predictable conflict, and a playful midnight movie setup delivered with Saulnier’s sharp formal precision.

Take the early sequence when one of the Ain’t Rights, the band name of the film’s East Coast punk rockers, drops the needle on the edge of a record to start a bash of hard-drinking fun. Rather than see the revelry, there’s a jump cut to the next morning, when the needle has played through to the record’s interior. Instead of watching the entire party, we only needed to see that it took the length of a vinyl album for the Ain’t Rights to get drunk and pass out. That’s clever filmmaking, and only about two seconds of the film. Green Room’s first shot finds the band’s ramshackle touring van driven halfway into a corn field, the driver having passed out. Siphoning gas from vehicles to make their low-key tour dates, the band prides itself on a raw punk philosophy. They avoid social media and marketing, play gigs for a few bucks per person, and embrace the live music experience.

Of course, there’s a touch of artifice inherent to a modern day punk band forcing themselves into the nasty lifestyle of yesteryear’s musical renegades. After all, these are millennials who carefully adopt a lived-in pretense. Saulnier uses this artificial characteristic once the film turns into a bloodbath and our guitar heroes are forced into a real-life situation. Turquoise-haired singer Tiger (Callum Turner) seems the most punk-stalwart of them all, followed by the hotheaded drummer Reece (Joe Cole), whereas bassist-manager Sam (Alia Shawkat) seems more level-headed, and guitarist Pat (Anton Yelchin) remains most sympathetic. Together, they drive out to the sticks to play a pickup gig for cash at a white-power club, although the aerial views of the drive there make it feel like they’re headed to The Overlook Hotel in The Shining.

Once again, Saulnier’s title represents the majority of the film’s setting: a room in the back of a dingy club owned by “a movement, not a party” of fascists deep in the forests of Oregon. The Ain’t Rights open with a big F-U to the crowd, playing The Dead Kennedys’ “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” to a throng of white supremacists. Despite the insult, their set goes on without incident—and they could have left scot-free had they not seen a dead body lying in the club’s green room, at which point the employees, including the gun-toting Big Justin (Eric Edelstein), hurry the band into the titular room and lock the door, refusing to let them leave. There’s a strange calmness to the clan holding the band. “We’re not keeping you,” they claim. “You’re just staying.” And the band cannot help but believe the lies during the initial negotiation process, if only because they’re so afraid that they must believe there’s a way to escape this horrifying situation.

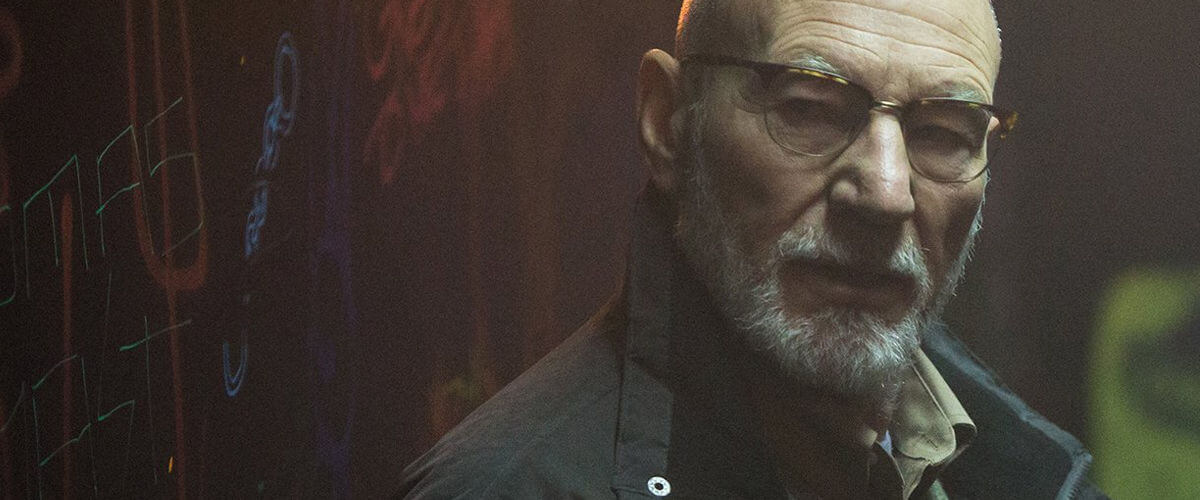

The reasons for the murder and the band’s detainment are revealed over time, but the tension comes from the gradual breakdown of several characters who are trapped, and later consider the green room refuge from the neo-Nazis, along with fellow prisoner Amber (Imogen Poots). Saulnier’s villains are every bit as developed as the Ain’t Rights; he turns the screw by portraying them as organized and layered in spooky ways. Macon Blair, star of Blue Ruin, once again uses his everyman looks and weak, compassionate eyes to create a curiously sympathetic skinhead, Gabe. Whereas Kai Lennox plays Clark, the wrangler of pit bulls trained to attack at his German-language order (we come to dread the command “fass”, meaning bite). These two, and a small army of skinheads, are devoted to the film’s most terrifying character: Patrick Stewart plays against type as Darcy, the cold, calculating organizer and overseer who has the unquestioned devotion of his “Red Laces”—youthful drones identified by the red shoe laces they earn after demonstrating their worthiness to Darcy. To be sure, Darcy is a far cry from Captain Picard or Professor X.

The film’s two opposing, nonconformist attitudes make for a clash of ultra-violent, increasingly gruesome attacks. Saulnier never hints at who will die next, and indeed, no one is safe from Green Room’s barrage of machetes, box cutters, guns, and bloodthirsty dogs. When death arrives onscreen, it’s unceremonious and unflinching—and what’s more, realistic looking. The fleshy, meaty wounds left on an arm by a machete will forever be burned on the mind of Green Room’s audience; the effect demands audible groans and gasps from the audience (this critic among them). Saulnier’s treatment contains a Carpenter-esque quality, adopting those claustrophobic situations explored in Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) and Ghosts of Mars (2001), where two unlikely characters band together against a common enemy. Although Saulnier doesn’t deconstruct his characters as thoroughly as he did in Blue Ruin, the affable cast members lend a wealth of presence. Green Room seems more interested in taking apart the punk and fascist façades, ultimately determining the more dangerous and scary of them are the white supremacists who live and breathe their upsetting dogma, whereas punk rockers have adopted their regime as an image.

An amusing ongoing joke develops in the form a conversation asking, “What’s your desert island band?” The answers are shared and changed over time, revealing much about our characters given their choices throughout the discussion. It’s these kind of moments that make Saulnier’s writing crisp and smart, while his technical filmmaking is equally sharp. Green Room bows confident lensing by cinematographer Sean Porter, appropriately green-hued for much of the film, and composed, gritty production design by Ryan Warren Smith. Having won several small awards and praise on the festival circuit in 2015, Green Room is sure to find a devoted audience over time, turning this into the cultish row it wants to be. Nevertheless, Saulnier’s third film manages to be much more than a prime selection for Midnight Movie Madness, requiring more serious moviegoing crowds to seek out this title for a rare sampling of an intelligent, well-made, and relentless thriller.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review