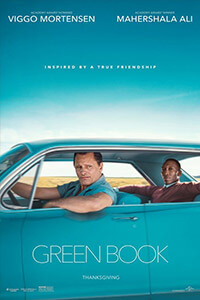

Green Book

By Brian Eggert |

Green Book pairs a tough Italian-American chauffeur with a Jamaican-born pianist from high society in a road movie that ventures into the pre-integration South of 1962. Based on a true story, the buddy comedy plays like a role reversal of Driving Miss Daisy (1989), except funnier and far less content with itself as lighthearted fare. Viggo Mortensen and Mahershala Ali star, their odd-couple characters clashing on issues of race and class to sometimes hilarious, sometimes sobering effect. And while it might be tempting to dwell on its director—Peter Farrelly, one half of the Farrelly brothers team that made Dumb and Dumber (1994) and There’s Something About Mary (1998)—to sell the movie’s humor and entertaining performances, there’s a streak of historical outrage exposed in this Universal release. The open racial intolerance depicted in the movie reflects a time not long ago when a well-educated, supremely talented, and wealthy person of color traveling through the South was subject to danger. If Green Book seems to naively behave as if such racism has disappeared, it at least offers a worthy message about the importance of having empathy for those outside of your immediate cultural sphere, regardless of their race, sexuality, or religion.

Fresh off his Oscar for Moonlight (2016), Ali plays Dr. Don Shirley, a prodigy with doctorates in psychology, music, and liturgical arts; he speaks several languages and can play Chopin or Tchaikovsky better than anyone; and he holds himself in high esteem, first appearing onscreen in regal silk, gold jewels, and seated on a throne inside his apartment above Carnegie Hall. For a planned eight-week concert tour that will take his trio, including his bassist (Mike Hatton) and cellist (Dimiter Marinov), on the road from New York to the Deep South, he requests the services of a driver who also functions as a bodyguard. Enter Tony Vallelonga (Mortensen), a Bronx native and Copacabana bouncer with tested skills as an enforcer. Tony also harbors an ingrained prejudice against African Americans, evidenced in a scene when his loving wife Dolores (Linda Cardellini) offers two Black plumbers a glass of lemonade. Tony reacts by dropping the empty glasses in the garbage, a response that Dolores remains opposed to yet muted about, despite rescuing the drinkware. Nevertheless, Tony accepts the job, given the lucrative pay and Shirley’s promise that they’ll return by Christmas.

Underneath the 30 pounds he put on to play the role, Mortensen plays Tony as an amusing blend of goombah street smarts and cultural unworldliness. After his turn in Captain Fantastic (2016), it’s a pleasure to see the actor flexing his rarely used comic muscles again. The script by Nick Vallelonga, Brian Currie, and Farrelly makes almost every line out of Tony’s mouth a potent one, whether he’s demonstrating his narrow perspective, successfully conning someone, or boasting about his victory in a hot dog-eating contest (Tony’s voracious appetite is a running gag, riotously punctuated in a scene where he picks up an entire pizza, folds it like a taco, and begins to chow down). People in his neighborhood call him “Tony Lip” because he’s a hustler—or “bullshitter” to use his word—capable of convincing others to do things they don’t want to do. There’s a scene where Tony, astounded that Shirley has never tried KFC—“But your people love fried chicken,” he says—convinces his erudite employer to eat finger food. Shirley, meanwhile, tries to impart upon Tony a sense of ethical responsibility rooted in personal dignity, far removed from Tony’s street rules, as demonstrated in a scene where Shirley confronts Tony for stealing a rock from a roadside vendor.

The relationship that develops between “Doc,” as Tony calls him, and the thick-headed driver becomes a clash of, and personal education in, racial preconceptions and class ideology. Doc demands that Tony stop smoking in his presence and work on his diction before speaking in front of their preeminent clientele. “If people don’t like the way I talk they can go take a shit,” replies Tony. But the pianist proves that his upper-class identity has isolated him from any knowledge about Black culture. Doc plays for the wealthiest and most exclusive white audiences in America, but he knows nothing of Chubby Checker, Sam Cooke, Little Richard, or Aretha Franklin. He considers himself above such things, whereas Tony’s experiences in a New York nightclub have left him versed in and unfazed by certain perspectives, such as the revelation of Doc’s sexuality. At the same time, Doc’s tour of the south is revealed to be a self-imposed test to learn about prejudice, and the lessons range from belligerent traffic stops to appalling, if not unexpected behavior from his superficially elevated white hosts. In some cases, Doc requires that Tony comes to the rescue; later, he makes a stand for himself. Predictably, both characters learn a lot about themselves and each other and become great friends in the process. And then there’s the issue of room and board, which is a decided problem for Doc when traveling below the Mason-Dixon line and “no coloreds allowed” signs become commonplace.

The book mentioned in the movie’s title is based on both Victor Hugo Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book, as well as Travelguide (Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation), two guidebooks published between the 1930s and 1950s, designed to aide Black drivers toward welcoming restaurants, roadside lodging, and automotive services. The ideal of the open road as a free public space was a symbol of American freedom after World War II and during the Cold War. Mobility on the public road without obstruction was a romantic conception of America, but it was also a fallacy, as African Americans traveling by car on city streets or state and federal highways might find themselves pulled over by police, or maybe a gang of racist white locals, for no reason whatsoever except the color of their skin. These guidebooks were symbols of Black immobility and remained in circulation in the Jim Crow South well into the 1960s, during a period when people of color in the south lived on the margins of freedom, caught between their enslaved past and the promise of something better. And the simple right to move about without persecution, although seemingly improved in the last fifty years, remains in question given today’s rate of police shootings and traffic stops involving African Americans.

Like other accessible period movies that expose and condemn racism, such as The Help (2014) or Hidden Figures (2016), Green Book treats its subject as though such events occurred in the distant past. Production designer Tim Galvin and costumer Betsy Heiman deliver a convincing portrait of the United States in the 1960s, and director of photography Sean Porter shoots the movie in pale colors that reflect the period’s temporal distance from today. The filmmakers make it seem like another world, whereas the reality is Black immobility has not yet been eradicated. Consider a sequence in which Tony and Doc find themselves pulled over in Mississippi, and the abrasive small-town cop throws them in jail after a hostile interaction. The audience can watch this scene and thank goodness for the end of sundown laws, but that doesn’t mean the problem of racism or racial profiling in traffic stops has disappeared. And so, it’s curious but not without reason that Farrelly’s movie should open the same year as BlackKklansman, Blindspotting, The Hate U Give, and Monsters and Men—all post-1960s movies that involve white police officers either shooting or becoming violent with people of color.

Beyond the endearing friendship that develops between the racially and culturally mismatched Doc and Tony, the marriage between Tony and Dolores imbues Green Book with a romantic subplot. Inarticulate in the letters home demanded by his wife, Tony scribbles misspelled accounts of his diet and experiences on the road until Doc insists on helping him. Doc dictates flowery and poetic language for Tony’s letters, and the cutaways to Dolores and her female friends swooning or teary-eyed over the prose lend a charming undercurrent to the otherwise serious themes here. As one might expect, Farrelly keeps the tone of Green Book rather light, regardless of a few ugly moments of racist behavior. In fact, the movie’s structure and home-for-the-holidays ending bears more than a resemblance to the finale of John Hughes’ Planes, Train and Automobiles (1987). Similar to John Candy’s role in that film, Doc is more tragic than he admits, spending each night of the tour finishing off a bottle of Cutty Sark whisky, feeling isolated by his class and racial identities. (Alas, don’t expect a scene where Doc and Tony awake one morning after sharing the same bed, with Tony’s hand between two pillows—wait, those aren’t pillows!)

Beyond the endearing friendship that develops between the racially and culturally mismatched Doc and Tony, the marriage between Tony and Dolores imbues Green Book with a romantic subplot. Inarticulate in the letters home demanded by his wife, Tony scribbles misspelled accounts of his diet and experiences on the road until Doc insists on helping him. Doc dictates flowery and poetic language for Tony’s letters, and the cutaways to Dolores and her female friends swooning or teary-eyed over the prose lend a charming undercurrent to the otherwise serious themes here. As one might expect, Farrelly keeps the tone of Green Book rather light, regardless of a few ugly moments of racist behavior. In fact, the movie’s structure and home-for-the-holidays ending bears more than a resemblance to the finale of John Hughes’ Planes, Train and Automobiles (1987). Similar to John Candy’s role in that film, Doc is more tragic than he admits, spending each night of the tour finishing off a bottle of Cutty Sark whisky, feeling isolated by his class and racial identities. (Alas, don’t expect a scene where Doc and Tony awake one morning after sharing the same bed, with Tony’s hand between two pillows—wait, those aren’t pillows!)

Green Book is a crowd-pleaser, and so watching it with a large audience is both essential for its maximum effect but revealing, depending on the audience. A movie theater packed with attuned viewers enhances our emotional reaction. Perhaps because the full house at the opening night screening of the Twin Cities Film Festival so thoroughly, and vocally, enjoyed the movie, I did too. When everyone’s laughing around you, you can’t help but laugh a little more than you might otherwise. It’s one of the essential benefits of cinema as a communal experience, and it’s how Green Book should be seen. But there’s also a downside. When characters engage in humor that’s not politically correct, and the predominantly white, bourgeois audience feels perhaps too comfortable, their laughter can become somewhat troubling. As viewers chuckled at the use of outdated epithets, the response forced me to wonder whether they were laughing because they follow a so-called color-blind racial ideology, because such words make them feel awkward, or worst of all because they think such words are funny. It’s a difficult distinction to identify in the midst of a packed moviehouse. But I can safely say there were more genuine laughs than vocal recoils or uncomfortable laughter, which was disconcerting.

Nevertheless, when the movie isn’t testing how comfortable its audience is with public racial discourse and racial humor, it presents a tender and enjoyable hunk of Oscar-bait. Tears will be shed, laughs will be had, and crowds will love it. The viewer might not always feel good about how those reactions are achieved; despite the overwhelming feel-goodness of the experience, you can see Green Book’s gears operating. It tackles important issues without revealing the vile extent of racial hatred that occurred in the south at this time. It bears a modern-day relevance that seems to address certain political leaders with hopeful lines like “dignity always prevails.” And it’s airy enough that the viewer leaves feeling unscathed, generally pleased by the experience, and with some basic notions about social justice to consider. Above all, Ali and Mortensen give layered performances that may exist in a conventional brand of Hollywood moviemaking about race, class, and identity, but nonetheless manage to engage the viewer for over two hours.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review