Reader's Choice

Greed

By Brian Eggert |

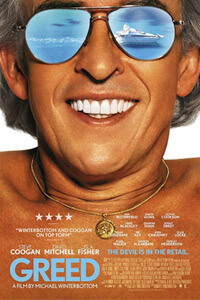

In Michael Winterbottom’s at once blithe and bleak satire of the super-rich, aptly titled Greed, Steve Coogan plays Sir Richard McCreadie, the so-called “Monet of Money,” also nicknamed “Sir Shifty” and “Greedy McCreadie” by those who despise this fictionalized retail tycoon, which is everyone. Since getting his start in the discount fashion market in the 1970s, McCreadie has perfected the art of the deal and thrived under the capitalist ideology of Thatcherism and Reaganism, exploiting cheap labor in Sri Lanka and using every angle he can to maximize profits. Winterbottom’s film centers on McCreadie’s sixtieth birthday celebration, where he appears with ridiculous orange skin and blindingly luminescent white teeth. The bash, situated on the Greek island of Mykonos, has all the trappings of a sordid Greek play and indulgent Roman gladiatorial celebration. Winterbottom’s on-the-nose critical symbolism doesn’t go to great lengths to hide its allusions to real-life retail billionaire Sir Philip Green and other one-percenters. And the writer-director would be the first to admit that reality, in this case, proves stranger, and more disturbing, than fiction.

There’s a free-flowing structure applied to Greed that, initially anyway, resembles Citizen Kane (1941)—where a journalist investigates his rich subject, and the interviews give way to flashbacks. Except here, the journalist is McCreadie’s dopey and trusting official biographer, Nick (David Mitchell), whose spinelessness and self-deprecating humor make him likable compared to the lion’s den of family members surrounding McCreadie. Nick interviews McCreadie’s past associates and family members, including his acerbic Irish mother (Shirley Henderson) who has a “fuck ‘em” attitude toward the British. The conversations cut away to 1973, while Winterbottom and his editor Liam Hendrix Heath jump around from “5 days earlier” to “3 months earlier” in a confusing framework. When he’s not conducting interviews with people who not-so-secretly despise McCreadie for his foul-mouth and bullying, or his inability to give a compliment without giving himself one in the process, Nick shoots painfully awkward “happy birthday” videos of McCreadie’s employees, some of them groan-worthy snaps of underpaid textile workers in Sri Lankan factories.

While Nick’s interviews color McCreadie’s backstory, Greed pushes forward with birthday festivities that have been arranged in homage of McCreadie’s favorite film, Gladiator (2000)—though ironically, he identifies not with Russell Crowe’s heroic general-turned-combatant but the resident emperor, played by Joaquin Phoenix, a sadistic (and incestuous) villain. In short order, McCreadie wants a miniature colosseum erected out of wood and paint, complete with a performing lion and a staff dressed in togas. When real-life celebrities decline his invitations, he hires look-alikes so that reporters in attendance can namedrop in the tabloids. No wonder his daughter (Sophie Cookson) looks for validation from her starring role on a reality show, whose production, in a padded but funny subplot, unfolds during the party planning. McCreadie’s angsty son (Asa Butterfield) is less convinced of his father’s lifestyle, making his sudden shift toward ruthless capitalism in the finale seem rather random. There’s also the competition between McCreadie’s new wife (Shanina Shaik) and his smarter, more voraciously manipulative ex-wife (Isla Fisher) to whom he issued a $1.2 billion check by manipulating the system.

Within Greed’s broad portrait of the vapid and heartless super-rich, Winterbottom’s biting commentary eschews subtlety. On the public beach next to McCreadie’s party, a group of Syrian refugees has camped out after making it across the Mediterranean, dampening his party’s mood. Resorting to a street hustler’s schemes, McCreadie enlists them as cheap labor and forces them into Roman peasant attire for the occasion. Also, on the periphery, one of McCreadie’s assistants named Amanda (Dinita Gohil) has family working in one of his sweatshops (earning four pounds for half a day’s work). By the time he demands that she too dress like a slave, matters have become pointed. References to both Oedipus and McCreadie identifying with Gladiator’s emperor suggest a bitter end for the central character, and the film doesn’t disappoint. Not that the audience cares much for a character—a man who hurls insults at employees, treats his string of bankruptcies as points of pride, attends a hearing about his tax evasion with Trump-like ego, and has established an empire on Monaco to avoid paying taxes (as billionaires tend to do).

Amid references to McCreadie’s fictional shops, with names like Monda and M&J, Winterbottom calls out actual retailers and super-companies (including H&M, Google, Apple, and Amazon) for their tax avoidance and exploitation of labor. Greed’s end credits sequence features facts and figures about everything from the division of wealth to the refugee situation to the income gap between genders, making the film an evident outpouring of frustration and humanist rage over the avarice of capitalism. Somehow, despite the film’s heavy themes, Winterbottom, Coogan, and the generous supporting cast make the material amusing and entertaining at the same time, even though the ending feels somewhat preachy and didactic. Still, Winterbottom opens and closes Greed with the same quote from E.M. Forster’s Howards End, beckoning viewers to “Only connect” and value personal relationships over, in this case, the accumulation of wealth. That almost no one makes such a human connection over the course of the film—not even the downplayed, would-be coupling between Nick and Amanda—speaks to Winterbottom’s dire assessment.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review