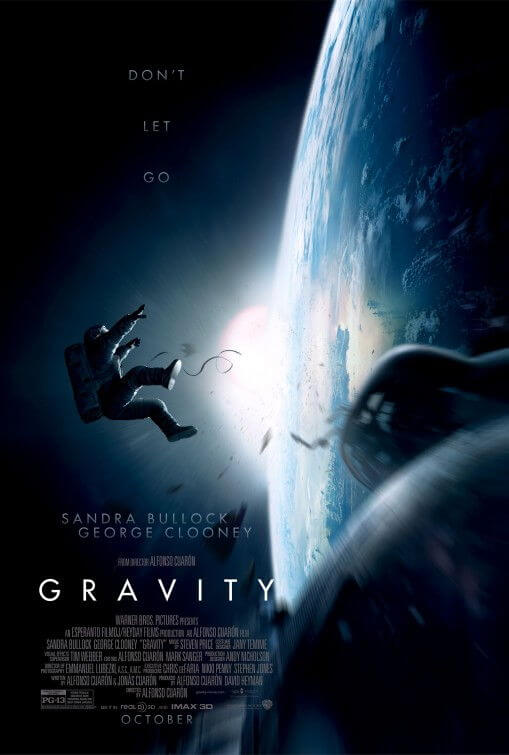

Gravity

By Brian Eggert |

For Gravity, director Alfonso Cuarón juggles dazzling computer-generated images, 3D technology, performances by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney on wires and in front of green screens, inspired visual choreography, and a miraculous use of camerabatics to conceive what is perhaps the most effective gut-reaction film in years. The straightforward narrative involves the survival of two astronauts after an unexpected accident leaves them stranded in space, a scenario where Murphy’s Law applies to every situation. Having co-written the script with his son Jonás, the Children of Men director sets out to make the audience feel like we’re in space, floating helplessly in a vast, soundless vacuum. All around is the beauty of the Earth, Sun, and stars for scenery, realized by way of landmark special effects. Though the presentation has more weight than the story, Cuarón develops an unparalleled visual experience that no words could adequately describe, and a theatrical experience no viewer will soon forget.

The narrative is simplicity itself, a basic story of survival but under the most impossible conditions. Rookie astronaut Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), a veteran on his last mission, orbit Earth on an assignment to complete improvements to the Hubble Telescope. For a while, Cuarón’s visual bravado is almost concealed under Kowalski’s charming banter with Mission Control in Houston. Stone, nervous and struggling to keep focus, replace damaged boards on the Hubble computer. Their third crewmember, Shariff (Paul Sharma), revels in the pleasures of weightlessness. All at once, the crew finds themselves in a cascading swarm of space debris which destroys their shuttle and leaves Shariff dead. Stone is untethered and catapulted into space, floating aimlessly in a struggle to survive in unlivable blackness. As the situation worsens, Stone is completely alone and faced with low oxygen, impossible odds, and few options. Her single goal is to get home, but how?

An unrelenting and exhausting 90-minute journey, the film puts the audience through the wringer with Stone, who reminds herself throughout to “enjoy the ride”. Bullock’s performance is a modest tour de force in which she must convey varying levels of panic and resolve, as Stone barely manages her fear during an almost unworkable set of circumstances. Being a tale of survival, the emotions on display are mostly primal and her character is best described as two-dimensional. And yet, it’s impressive that Bullock is able to convey so much, often through the face shield of her space suit. Though, it must be noted that, for a character who claims her favorite part of space is the silence, Stone is very talky, even when she’s alone. But the story moves so fast that the audience barely has time to notice how cleverly the script embeds details about Stone’s personal life, or how effective the dynamic between Stone and Kowalski proves to be. Although he’s onscreen for much less time than his costar, Clooney was perfectly cast as a charismatic astronaut whose experience makes space and the potential catastrophes therein a second home.

But before any catastrophe sets in, Gravity opens with a beautiful unbroken shot lasting some 13 minutes, where cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s fluid frame glides around the astronauts, maneuvering through elaborate NASA technology and even occupying Stone’s perspective from inside her helmet. As she looks down upon Earth, the lights of cities glowing, our political and national borders invisible, there’s an undeniable feeling of detachment from the complicated world below. It becomes apparent that Cuarón has long dreamt of being an astronaut and considered both the unique sense of freedom that accompanies space travel, but also its immediate dangers. With his film, he makes that dream come true for countless moviegoers who have often imagined what it might be like in space. And in a completely computer-generated setting, the possibilities are endless, and the director explores these conditions to their fullest degree, reshaping the boundaries of cinematic technology to achieve his vision.

After Stone makes her way to a station some 30-minutes in, there’s a moment where we see a pen drifting inside the gravity-less shuttle cabin, recalling the floating pen in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Cuarón’s nod also marks his awareness that, like Kubrick’s film, he’s breaking new ground. And much like Ed Harris voicing Mission Control as he also did in Apollo 13, Cuarón demonstrates that he’s fascinated with exploring the cinematic realization of space and doing it in such a way that outshines any such representation before. He’s always been well aware of his technical acumen, which is why he’s prone to placing a droplet of CGI blood or water onto the lens for all to see. Here, a crucial component of his objective is his expert use of 3D. Filmed digitally and converted to 3D in post-production, Gravity uses what is normally a gimmicky Hollywood ploy to create the sensation of weightlessness in the viewer, as though we’re drifting out there with Stone. Viewers prone to motion sickness, beware. Cuarón propels us through space, hurdles shuttle wreckage at us, and sends us crashing into objects without the capacity to slow down—and it’s also so shockingly real that the 3D glasses never once become a distraction. To be sure, Cuarón’s film surpasses Avatar and even challenges Life of Pi for the best use yet of 3D technology.

Gravity’s major faults reside in its development of Stone’s backstory and emotional rebirth. We gradually learn that she’s emotionally fragile and recovering from the recent loss of her daughter, now searching for a reason to live. Lost in space, she forgets about her reasons and almost wills herself to death. Of course, her desperate fight for survival is a reincarnation of sorts. Once she’s delivered from space at the first station and sheds her suit, she hovers in anti-gravity for a moment in the fetal position, and then later, she emerges from her crashed shuttle in the ocean onto a beach like some finned creature from the primordial ooze. The dramatic symbolism is effective, but the plausibility is unsound. Indeed, one must wonder if NASA’s strict screening process would ever allow such an emotional risk aboard one of their missions—especially after, as Stone admits, she crashed in every simulation. Moreover, if Stone had lost all reason to live because of her late daughter, as the film suggests, we cannot help but question how much passion she could have for the specialized project that earned her place on this mission. A person has to be quite impassioned to work through NASA training, but based on what we learn about Stone, she seems resigned to defeat until the film’s conditions revitalize her. As a result, throughout the film, the viewer questions how Stone was ever accepted into NASA and what she’s doing up there.

However, the most unbelievable part of Gravity is the character and not the representation of space is a testament to the technical marvel of the film. Cuarón’s ever-active imagination—demonstrated in his entry in the Harry Potter films, The Prisoner of Azkaban, the best of the series—has put this Hollywood production’s $100 million budget to extraordinary use and conceived an engrossing, almost primitive experience whose intellectual merits may be few, but whose execution is unparalleled. The film transports us 372 miles above the Earth’s surface, and never for a moment do we remember that we’re actually sitting in a movie theater, wearing goofy glasses and watching a projected image. Cuarón completely immerses his audience in the terrors and delights of space travel. And though the narrative doesn’t contain all of the dramatic pull implied by the title, for its technical and visceral achievements, Gravity is still something of a visual revelation.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review