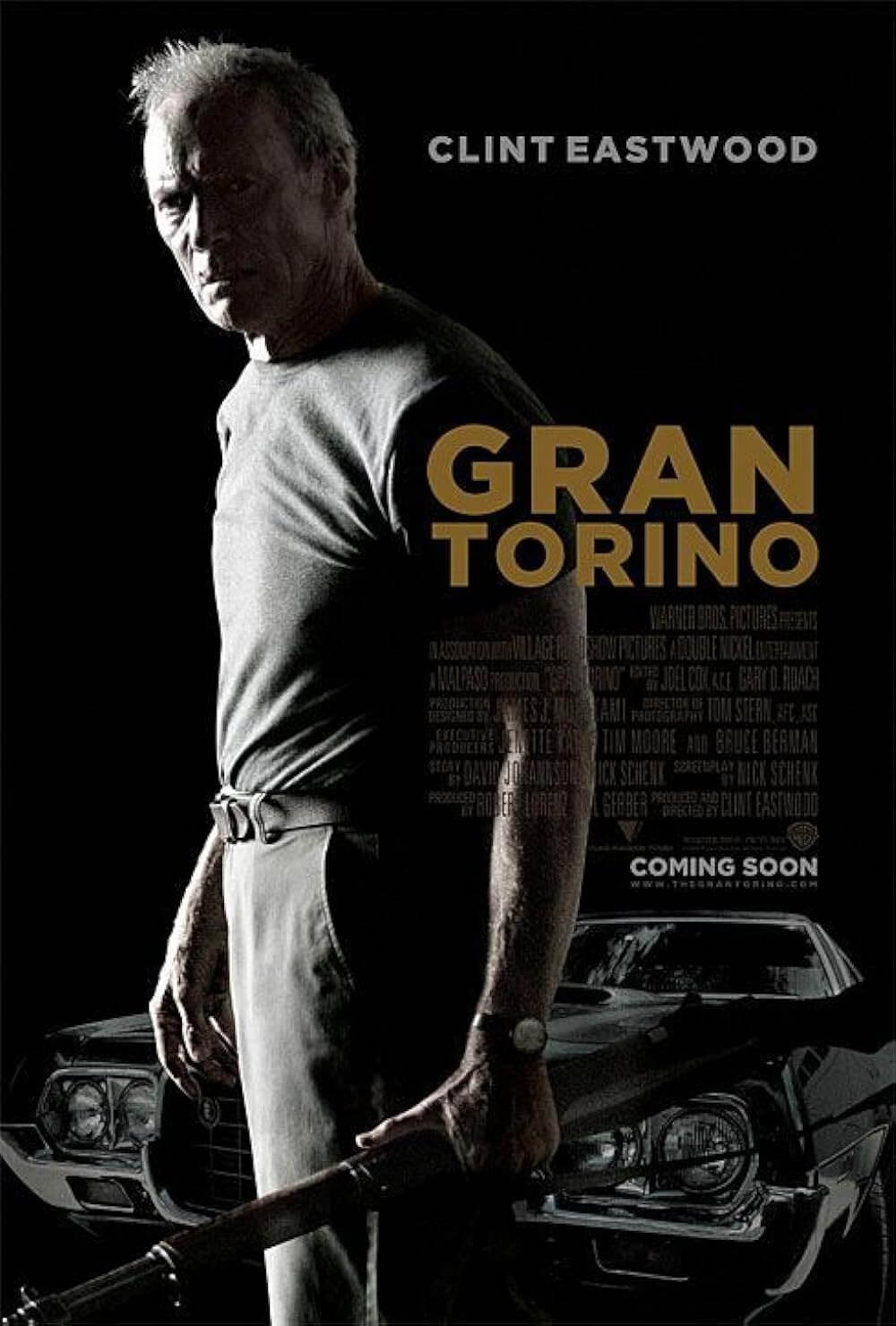

Gran Torino

By Brian Eggert |

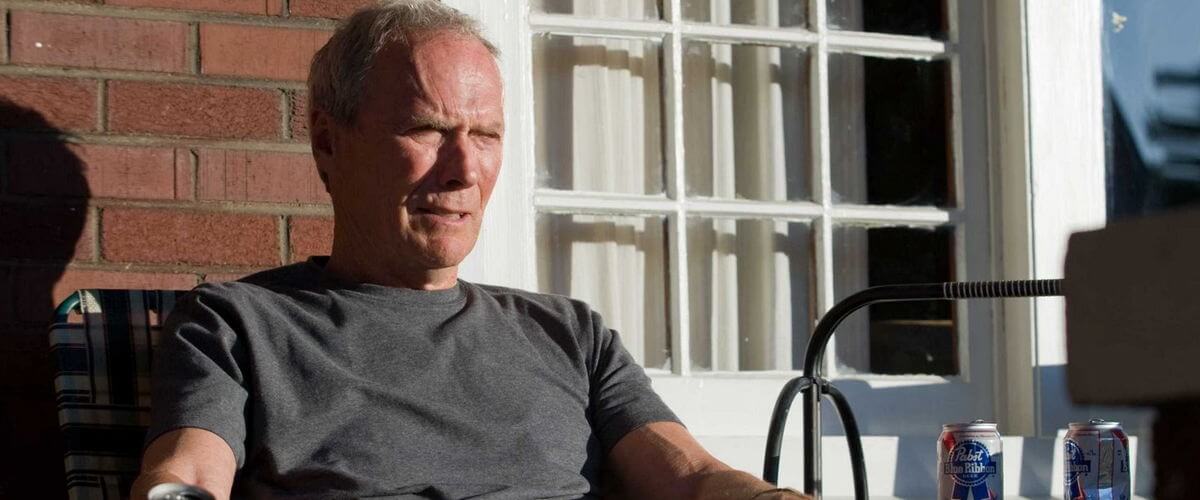

Walt Kowalski sits on his porch all day drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon and scowling at his “gook” neighbors. When he’s not doing that, he’s fixing things around his house, located in a neighborhood that has become predominately inhabited by Hmong families. Sometimes he wheels out his 1972 Gran Torino and polishes it, having helped build the machine on the original assembly line. He’s a Korean War veteran, a retired Ford plant auto worker, and a cantankerous old racist. And he’ll stake a proud claim to any of those points.

Clint Eastwood plays Walt in his latest directorial effort, Gran Torino, a film with surprising sensitivity and humanity, despite the dogged nature of its main character. Eastwood plays the role with appropriate growls and snarls, fervent comebacks, and harsh truth-telling. He’s the type of character who cares more about defending the boundaries of his lawn than what’s happening to the outside world. But there’s little out there for him to care about. His wife has just died, and his witless son (Brian Haley) has suggested Walt move into a senior assisted living “resort,” which, as you can imagine, doesn’t go over too well. Walt is not a religious man either, though he’s perpetually hounded by Father Janovich (Christopher Carley), who made a promise to Walt’s late wife to watch over him. The last thing Walt wants to feel is incapable of looking after himself.

Next door, the Hmong family sees him as an old rooster that doesn’t know when to give in. Since he calls them every name in the book from “chink” to “eggroll,” it’s no wonder they wish he’d leave. But Walt marked his territory long ago, and he’s not about to abandon a staked claim. So when the quiet teenage neighbor boy Thao (Bee Vang) is reluctantly enlisted into his cousin’s gang of Hmong thugs, they tell him to steal Walt’s Gran Torino for his initiation. Walt catches him in the act and probably would have killed him, except he slipped and the boy got away. Thao’s sensible and bright sister Sue (Ahney Her) brings her awkward brother over to apologize, offering his services to Walt to make amends by way of chores and such. Walt agrees, albeit grudgingly, and finds himself mentoring Thao.

What proceeds is a testament to Eastwood’s charisma as an actor and his dramatic sensitivity as a filmmaker. After all, having directed nearly thirty pictures in as many years and starred in many more for the last fifty, Eastwood has a profound grasp of dramaturgy. This is particularly true in his last few years since Mystic River, moving through Million Dollar Baby and his Iwo Jima diptych of Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, where Eastwood has composed himself with such artistry and patience in his filmmaking tone. He never intrudes on the story, never allows his presence behind the camera to be known in front of it. He’s a selfless artist, and how many artists can make that claim?

Audiences might expect the plot to enter Dirty Harry territory, as the gang attempting to initiate Thao persists, and who better to eliminate an unwanted gang than Dirty Harry? But now that Walt has identified with his neighbors, Asian though they may be, they’re under his wing. And so, perhaps Eastwood’s Dirty Harry persona does rear its ugly head, complete with lips unfurling to reveal clenched-jawed speeches. But not in the manner we’d expect. This isn’t a film about violent acts of retribution. Instead, it’s about seeing your neighbors as human beings, too, no matter how different their religions or racial profiles or upbringings may be. Indeed, Walt Kowalski remains a foul-mouthed bigot for the full procession of the film, but he also identifies more with the unity and family values of the Hmongs next door than his own family, who are just waiting for Walt to die so they can hear who gets what in the will reading.

Eastwood, supposedly in his last acting role, combines his hard-edged guise of yesteryear—the stuff of Dirty Harry and The Man with No Name—with his more recent humanity. The result delineates the transformation of a movie figure that used to blow people’s faces off, but now he prefers to understand them. Gran Torino is a nuanced picture with incredible heart, humor, and melodramatic themes of acceptance and long-overdue redemption. The story is told in simple terms without resorting to grand metaphors and preaches open-mindedness for your fellow Americans, race notwithstanding.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review