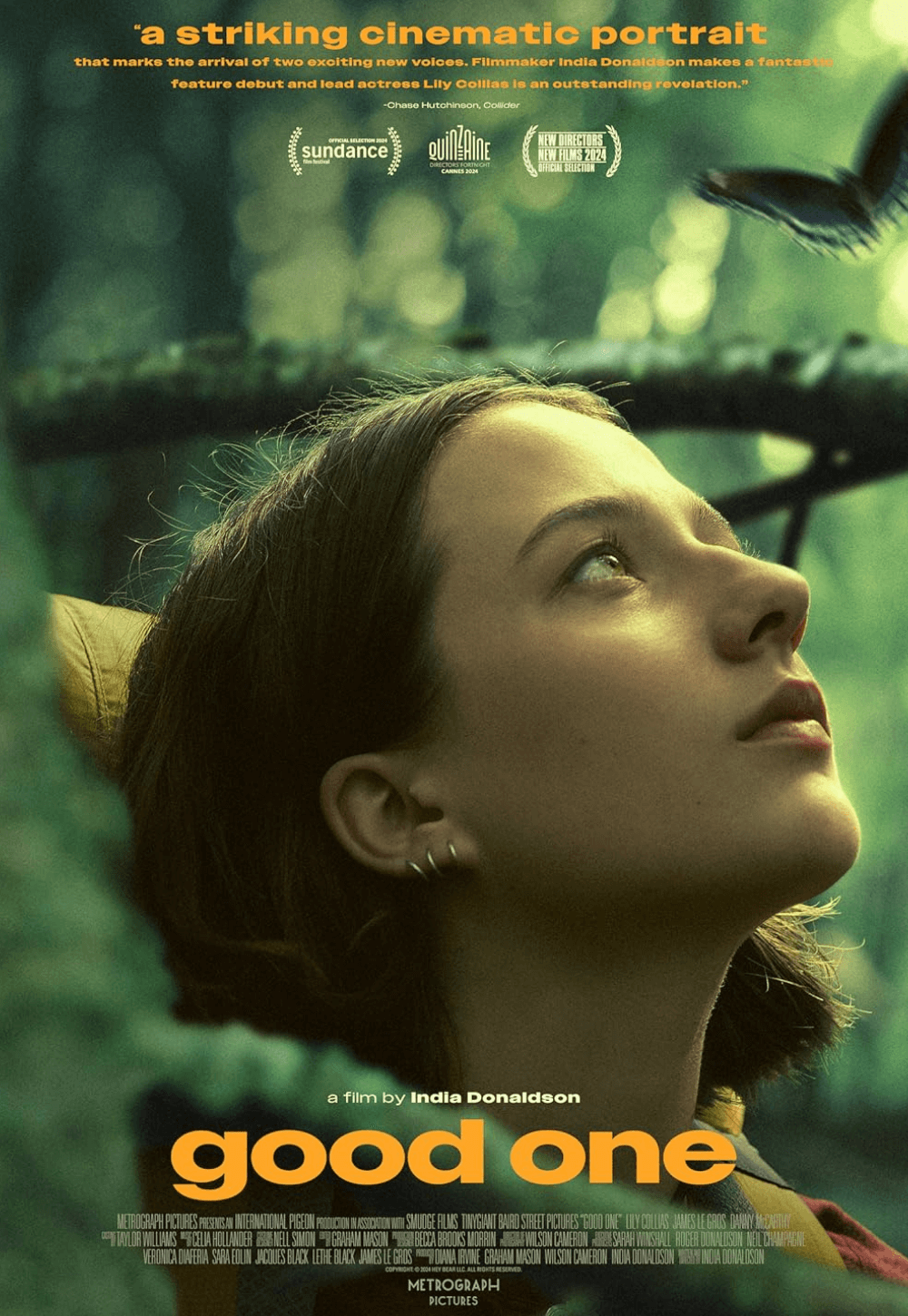

Good One

By Brian Eggert |

Beautifully observed and brimming with subtext, Good One is bound to be overlooked, perhaps even by the arthouse crowd. It’s a quiet, leisurely paced film where little seems to happen on the surface. And it arrives at the end of summer, amid a hodgepodge of second-tier studio tentpoles, and a couple of months before awards season kicks into gear. Situated here, the debut feature by writer-director India Donaldson feels like it will trickle between the cracks, snaking its way through today’s impossible theatrical market, which under-services independent projects, and then flow into and disappear within the vast ocean of streaming options. Those lucky enough to find this verdant creek of a film will savor its simplicity and purity, and how it says so much without needing to spell it out. No other release this year will capture the elusive ways that the microcosmic but loaded behaviors between people can prove shattering upon reflection, leaving one not quite shaken but thoroughly disappointed. More than almost any other film this year, Good One sneaks up on you, lingering there in your mind like a subtle offense that grows until it feels like a slap in the face.

Lily Collias plays Sam, a capable and independent young high-school senior bound for college in the fall. But first, she takes a three-day weekend camping and hiking in upstate New York with her father, Chris (James Le Gros), a contractor and divorcé who left Sam’s mother for a younger woman. They will be joined by Chris’ old friend, Matt (Danny McCarthy), a struggling actor who boasts that he just booked an IBS commercial. Matt’s teen son was also supposed to join them, but he refuses at the last minute. It could become a little uncomfortable, but Sam is observant and shrewdly honest. She can hold her own with the two men. At first, Matt is the outsider, coming unprepared and overpacked; he wears jeans and forgets his sleeping bag in the car. Chris is annoyed with his friend, but there’s a cavalier quality to Matt—he’s a talker, a little pathetic, but also kind of funny. Matt and Sam have a chummy rapport, too, swapping favorite meals, much to Chris’ annoyance and their delight. His presence might make him into the trip’s third wheel and destabilize Sam and Chris’s father-daughter dynamic. Instead, with no one of her age or gender on the trip, Sam begins to feel like the extra party in a middle-aged man duo.

Almost immediately, some viewers will think of Kelly Reichardt’s cinema. Donaldson has a quiet, watchful approach and an evident appreciation for Nature, similar to Reichardt. Graham Mason’s editing involves several montages of flora and fauna, streams of crystal water gently flowing, slugs crawling across the forest floor, and expansive panoramas overlooking a vast Catskills landscape that extends into the distance. The effect recalls First Cow (2020) or even moments in Wendy and Lucy (2008) and Night Moves (2013). These images, captured by cinematographer Wilson Cameron’s digital camera, achieve harmony with the gentle notes of Celia Hollander’s solo flute and acoustic guitar score, which often bridges scenes but recedes and allows the imagery and silences to fill the aural space between characters. And while the film’s aesthetic recalls several Reichardt films, the setup resembles Old Joy (2006) above all, following two friends in the Cascade mountains, dredging up the past and realizing how much they’ve grown apart.

Almost immediately, some viewers will think of Kelly Reichardt’s cinema. Donaldson has a quiet, watchful approach and an evident appreciation for Nature, similar to Reichardt. Graham Mason’s editing involves several montages of flora and fauna, streams of crystal water gently flowing, slugs crawling across the forest floor, and expansive panoramas overlooking a vast Catskills landscape that extends into the distance. The effect recalls First Cow (2020) or even moments in Wendy and Lucy (2008) and Night Moves (2013). These images, captured by cinematographer Wilson Cameron’s digital camera, achieve harmony with the gentle notes of Celia Hollander’s solo flute and acoustic guitar score, which often bridges scenes but recedes and allows the imagery and silences to fill the aural space between characters. And while the film’s aesthetic recalls several Reichardt films, the setup resembles Old Joy (2006) above all, following two friends in the Cascade mountains, dredging up the past and realizing how much they’ve grown apart.

For much of Good One, which unfolds almost entirely from Sam’s perspective, the viewer might think, Nothing is happening. They walk through trails, look out over peaks, and prepare modest campfire meals of ramen soup. But Donaldson builds the tension ever so gradually that you might not even notice. One night, the trio stays up late. The two men drink from Matt’s flask around a campfire, sharing stories about their personal failures and divorces, oblivious that Sam may not want to hear about their midlife crises. It also becomes evident that Chris’ fatherly confidence in the woods and Matt’s good humor mask their inability to look inward. Sam offers a wise appraisal of them, cutting through their delusions: “The worst doesn’t happen to you,” she tells them both. “You’re involved in the process.” What happens next, after Chris stumbles drunk to bed, is so slight yet charged—like the film’s title—that it changes the entire weekend for Sam. A disquieting incident with Matt reshapes how Sam looks at him and, eventually, her father. When Sam tells him what happened, Chris’ reply is devastating: “Can we just have a nice day?”

Good One is Donaldson’s first feature after the short films Medusa (2018), Hannahs (2019), and If Found (2020). Directing is a family business for India—she’s the daughter of director Roger Donaldson, who burst onto the New Zealand New Wave scene with Sleeping Dogs (1977) and Smash Palace (1981) before turning into a Hollywood journeyman responsible for The Bounty (1984), No Way Out (1987), Cocktail (1988), Species (1995), Dante’s Peak (1997), and many others. He also serves as a producer on his daughter’s first feature. Though, her style and subject matter are far removed from her father’s output. Whether she develops a consistent style that emerges out of Good One or takes on director-for-hire work like her father remains to be seen, but her work here is exemplary. If the similarities to Reichardt’s cinema could be bothersome to purists, it’s nonetheless just as richly layered and loaded with meaning without relying on pastiche. Donaldson’s influences evaporated from my mind a few minutes into the film, and her work cast its spell.

The film’s enchanted athame, the device in Donaldson’s filmmaking bag of subtle magic that elevates every aspect of Good One, is Lily Collias, whose resoundingly natural and sharp-eyed presence adds subtext to every scene. It’s an extraordinary performance, at first glance concealing the unease in her expression. But the longer the camera stays with her, the more signs of her discomfort over the situation and disillusionment with her father emerge. When Chris admits, “I guess I just don’t get it,” it’s a dismal reply. His attempt to make it better with a small gesture of trust hardly resolves the betrayal, leaving Sam to face the world, feeling alone. She is already uncomfortable enough on the trip, having to go off into the woods, full of hikers and male bonding, to change a tampon—which, because she conceals it, adds to her secret sense of feeling different. While that distinction remains internalized for Sam, the entire weekend’s behaviors add up to an overwhelming and evocative underscoring of gender dynamics that I found fascinating and understated, yet they invaded my mind in the days to come. Collias and her two costars play these moments wonderfully.

After Good One debuted at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Metrograph Pictures acquired North American rights to the indie. Now led by former A24 exec David Laub and better known as a repertory outfit out of New York, the company restores and distributes classics from an impressive array of arthouse filmmakers, such as Claire Denis (L’Intrus, 2004), Hou Hsiao-Hsien (Millennium Mambo, 2001), and Andrzej Zulawski (Possession, 1981). They also have an excellent streaming service, Metrograph at Home. Donaldson’s film feels on-brand for Metrograph, containing a narrative structure so fragile that to describe the conflict at all might be giving too much away. But Good One isn’t concerned with articulating the point with overstated dialogue or resolving anything for the viewer, just as Sam receives no real closure in the end. That may be frustrating for some. However, with authenticity and delicately conveyed disappointment, Donaldson has captured how these liminal situations reshape our worldview and forever change our understanding of how things work.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review