Gone Girl

By Brian Eggert |

More than the poetry of misdirection, more than disappearances or curdling doubt, more than sinister motives or cunning manipulation, and more shocking than a singularly violent, bloody death, David Fincher’s Gone Girl is a portrait of marriage. And while these other threads run through Gillian Flynn’s novel too, the faithful screenplay adaptation that the author wrote from her book reveals marriage as a careful interplay of deceiving courtships that collide like two rams butting heads but locking horns so that they’re unable to dislodge, forced to coexist with one another but desperate to escape. Flynn’s twisting 2012 bestseller perfectly aligns with Fincher’s sensibilities as a director and his pessimistic exploration of the psychological terror lurking under the surface in Se7en, Fight Club, and even The Social Network. And like many Fincher films, Flynn’s plot mechanics rely on secrets that unravel through the course of the story, and any analysis of the film’s power must consider those secrets in detail; consider yourself forewarned.

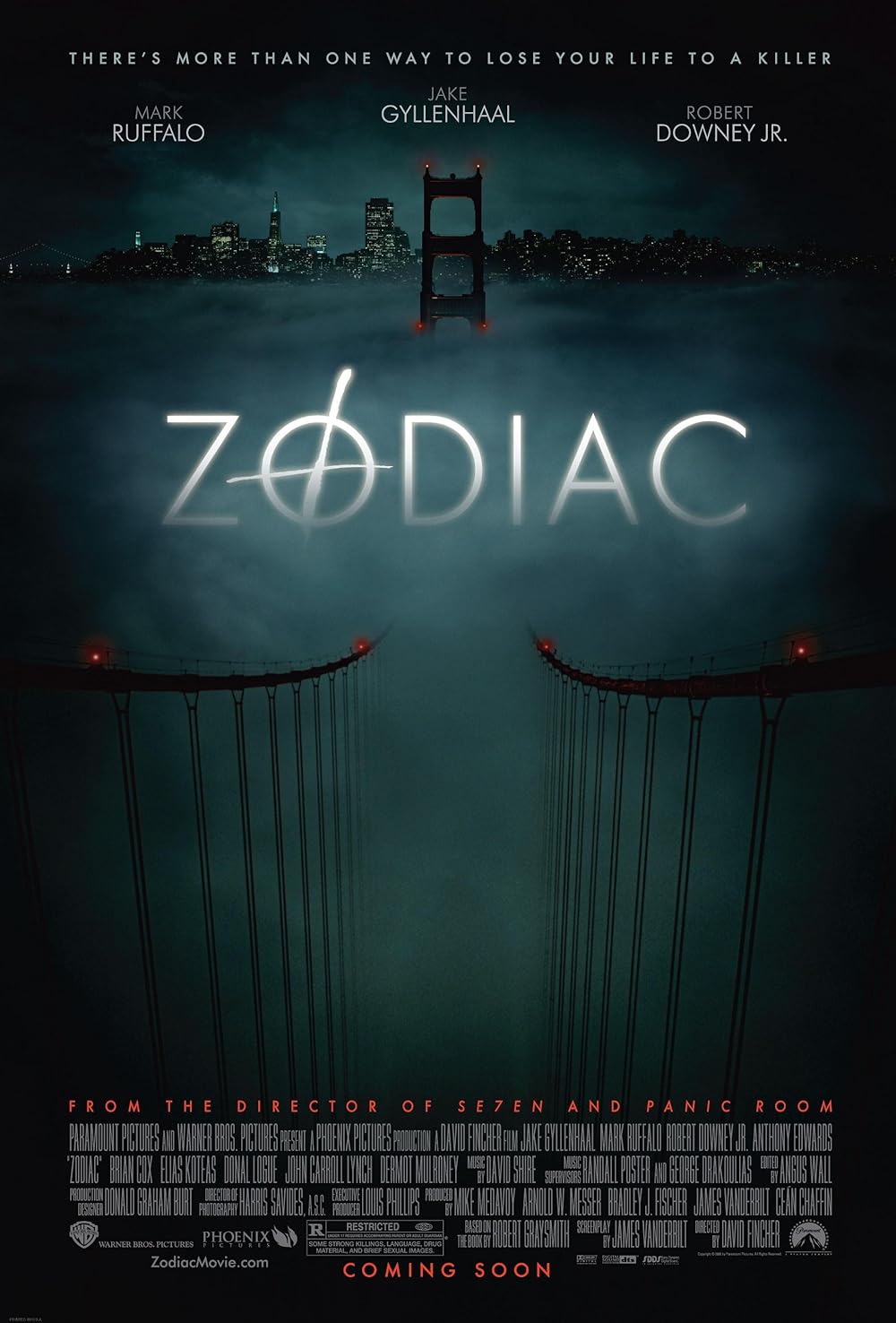

The story details a media frenzy and shifting suspicions when a lady vanishes and her husband gradually becomes the prime suspect. Fincher’s film dissects the marriage of Nick and Amy Dunne (Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike) with all the surgical precision of his crime procedurals Zodiac or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, employing the book’s alternating perspectives in an inventive way for cinema. Whereas Flynn’s novel alternated chapters between Nick and Amy’s perspectives, film is a medium in which the viewer believes what they see. To preserve the mystery, we see much of the story from Nick’s perspective, while Amy’s portion, for the most part, is read from her diary, complete with the fond remembrances of their courtship and, ultimately, the apprehensions she begins to feel around her husband. And much like Fincher’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the director applies his meticulous talents to carefully break down the complex centerpiece—the Dunne’s marriage—bit by bit over a swift, 149-minute runtime of technically exquisite filmmaking.

Even Gone Girl‘s opening credits have metaphoric intent. The film begins with shots of dilapidated small-town façades affected by the financial crisis. A pair of New York writers living in an elegant brownstone, Nick and Amy survive on her sizable trust fund, as she was the subject of the popular Amazing Amy children’s books written by her parents (David Clennon and Lisa Banes). But the carefree bliss that landed them together soon dissipates. Layoffs from their jobs leave Nick feeling bored and helpless; then Amy’s parents need money, and Amy happily gives up her next egg. And matters get worse when Nick’s mother gets ill, forcing the couple to uproot to his Missouri hometown. Before long, it’s evident that her sophisticated, ivy league sensibilities conflict with his Midwesterner pedigree. He takes a job teaching a college writing course, where he beds one of his students (Emily Ratajkowski). He also owns a local bar, which Amy bought for him, with his sister Margo (Carrie Coon). Amy, meanwhile, stays home alone, with the resentful Nick neither aware nor curious of what his intelligent, beautiful wife does all day.

But this is all backstory filled in later. The first scenes show Nick waking up on their fifth wedding anniversary, visiting Margo at the bar, and returning home to find signs of a struggle. He calls the police, and due to Amy’s semi-celebrity status, an investigation begins immediately. Det. Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) and her partner (Patrick Fugit) find curious clues: an overturned table, some blood spatter, and a pool of blood that’s been ineffectually cleaned up. Has Amy been abducted or possibly murdered? There’s also Amy’s annual anniversary treasure hunt for Nick in the form of clues whose riddles lead one step closer to his gift; this year, each clue cleverly underscores one of Nick’s failings in their marriage. At the same time, Amy’s parents establish a tip line and public awareness campaign for which Nick makes awkward public appearances. He politely, if inappropriately, smiles for the cameras. In a sense, Gone Girl becomes a critique of the media’s frenzied obsession with such cases, shown through the speed at which public opinion of Nick changes as each new bit of information about the case is revealed. He’s also hounded by reporters, among them a sensationalist, Nancy Grace-like witch hunter on television (Missy Pyle).

But this is all backstory filled in later. The first scenes show Nick waking up on their fifth wedding anniversary, visiting Margo at the bar, and returning home to find signs of a struggle. He calls the police, and due to Amy’s semi-celebrity status, an investigation begins immediately. Det. Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) and her partner (Patrick Fugit) find curious clues: an overturned table, some blood spatter, and a pool of blood that’s been ineffectually cleaned up. Has Amy been abducted or possibly murdered? There’s also Amy’s annual anniversary treasure hunt for Nick in the form of clues whose riddles lead one step closer to his gift; this year, each clue cleverly underscores one of Nick’s failings in their marriage. At the same time, Amy’s parents establish a tip line and public awareness campaign for which Nick makes awkward public appearances. He politely, if inappropriately, smiles for the cameras. In a sense, Gone Girl becomes a critique of the media’s frenzied obsession with such cases, shown through the speed at which public opinion of Nick changes as each new bit of information about the case is revealed. He’s also hounded by reporters, among them a sensationalist, Nancy Grace-like witch hunter on television (Missy Pyle).

Det. Boney, and therein the audience, take a magnifying glass to the Dunne’s marriage. We question why Nick doesn’t really know what his wife does with her time, while mounting evidence of Nick’s financial troubles and tension in the marriage, especially around the subject of children as identified in Amy’s conveniently detailed diary, leads to further suspicion that he’s the culprit. A nosy neighbor (Casey Wilson) confirms Amy’s apprehensions about Nick and his violent tendencies. Enter high-powered defense attorney Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry), who, along with Margo, begins to believe Nick’s private story that his wife is actually a master manipulator who has staged an elaborate scheme to frame Nick for her death. When the film suddenly cuts to Amy, alive and well, and details her intricate frame-job—that includes fabricating clues, convincing third-party testimonials, and her entire diary—the moment feels less like a plot twist than another facet of these multi-faceted characters’ lives. She has long suppressed her happiness and watched as Nick drifted and no longer cared about making her happy, and she’s not the type to stand idly by and remain out of control. After her quiet escape to the Ozarks proves a wash, she calls upon Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris), a suave ex-boyfriend devoted to pampering her to creepy extremes, and watches the news coverage of Nick’s fall in the media with bated breath. Meanwhile, she’s finally able to stop performing and relax with a diet of Kit-Kats and a second helping of crème brûlée.

Gone Girl wouldn’t work if not for its astounding lead performers. Affleck has been perfectly cast as Nick, a role that requires him to be an affable, somewhat aloof everyman like the one he played in The Company Men, and yet project something that suggests he’s both a victim and a villain as in The Town. But it’s the lesser-known Pike who proves deftly inscrutable as Amy, a character capable of beguiling and frightening her husband. Known for smaller roles in 2005’s Pride & Prejudice or, more recently, The World’s End, she breathes icy life into Amy and somehow manages to be sexy, scary, and fascinating all at once. Pike has never achieved anything remotely close to this performance, and in any given scene, displays a multitude of possibilities—she’s always poised, calculating, seems in control and almost never lost in the moment, and however intimidating, she remains oddly desirable. It’s impossible to imagine another actress catching us off guard the way Pike has here, and not unlike Rooney Mara in Fincher’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, it’s an Oscar-worthy breakthrough. The supporting cast is just as expert, the standouts being Coon, Dickens, and Perry.

Versed in complex thrillers and cinematic reversals, Fincher’s expert, but less flourished, visual style recedes next to the intricacy of Flynn’s complex narrative, as do the buzzing electronic sounds of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ moody score. But the genius of the film belongs to Flynn and how her mystery plot doubles as a character study. Think about the author’s twists and turns less as plot points than another piece to her three-dimensional puzzle that is Nick and Amy’s marriage. Though each reveal brings us closer to solving the film’s mystery, it also plunges us deeper into these characters’ intricate lives, representing marriage as a kind of ongoing performance art where each participant must cautiously choose the precise moment for an allegro or arabesque. The more detail we have about these characters, the more their manipulation of one another becomes increasingly horrifying, leaving us to acknowledge how marriage, some of them anyway, becomes a process of denying one’s self to play the role expected by a spouse. That kind of performance becomes the inescapable focus of Nick and Amy’s marriage, resulting in a deftly cynical view, but also rather comical in the darkest of ways, and even a little fitting. Indeed, these two deserve each other.

Versed in complex thrillers and cinematic reversals, Fincher’s expert, but less flourished, visual style recedes next to the intricacy of Flynn’s complex narrative, as do the buzzing electronic sounds of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ moody score. But the genius of the film belongs to Flynn and how her mystery plot doubles as a character study. Think about the author’s twists and turns less as plot points than another piece to her three-dimensional puzzle that is Nick and Amy’s marriage. Though each reveal brings us closer to solving the film’s mystery, it also plunges us deeper into these characters’ intricate lives, representing marriage as a kind of ongoing performance art where each participant must cautiously choose the precise moment for an allegro or arabesque. The more detail we have about these characters, the more their manipulation of one another becomes increasingly horrifying, leaving us to acknowledge how marriage, some of them anyway, becomes a process of denying one’s self to play the role expected by a spouse. That kind of performance becomes the inescapable focus of Nick and Amy’s marriage, resulting in a deftly cynical view, but also rather comical in the darkest of ways, and even a little fitting. Indeed, these two deserve each other.

Reports that Flynn dramatically altered the finale for the screen adaptation were grossly exaggerated, if not wholly untrue; the story and significant plot elements remain intact, with only slight trimming to streamline her novel for moviegoing audiences. Fans of the book will see everything they want to see, performed to perfection by Affleck, Pike, and the excellent supporting cast, and filmed with an unselfish stylization by Fincher. Recalling everything from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca and Psycho to the relatively more recent Fatal Attraction, Fincher’s film belongs on a shortlist of culturally significant films about modern relationships that also happen to be immaculate thrillers. When the final shot cuts to black and the credits begin to roll, moviegoers in this critic’s screening called out wondering, “Is that it?”—as if expecting either Nick or Amy to receive their comeuppance. Except, the ending of Gone Girl identifies the film, not as a twisting mystery but as a portrait of a marriage. If you’re uninitiated, watch it once to get the mysteries out of the way, and then watch it again to examine how Flynn has carefully designed Nick and Amy’s marriage as a prison where both parties are behind bars, yet both have keys to the cell. Such a dramatic dynamic is far more compelling than simply revealing the secrets of a whodunit; rather, it’s a metaphor for how little we know about the people with whom we choose to spend our lives.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review