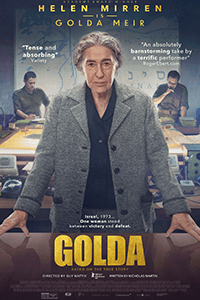

Golda

By Brian Eggert |

Golda paints a portrait of Golda Meir, Israel’s fourth Prime Minister, by depicting her response to the 19-day Yom Kippur War in 1973. The approach recalls Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012) and Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour (2017), as both sought to understand their leaders by examining how they negotiated a singular conflict. How do they juggle the responsibility of their country’s future and their personal relationships? What do these situations say about their reputation in their respective countries and on the world stage? Far from a traditional birth-life-death biographical drama, the packed screenplay by Nicholas Martin (Florence Foster Jenkins, 2016) rushes through or altogether ignores details about Golda’s life that might add necessary context for those unfamiliar. The uphill challenge for director Guy Nattiv is overcoming how to include enough historical exposition while maintaining the dramatic momentum. And while all of these considerations might prove demanding enough, something so simple as the prosthetic makeup on Helen Mirren threatens to derail the production altogether.

Focused on the events that began on October 6, 1973, when the combined militaries of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel, and during Ramadan, no less, Golda occupies conference tables and war rooms filled with cigarette smoke. Most of the smoke comes from Golda, who lights her next cigarette with the last while she debates military strategy with her generals and Mossad intelligence. Something in her gut suggests an attack is coming; she even considers a preemptive strike. But while she debates the issue with her cabinet, the alarms sound. Soon after, Israel’s forces are slaughtered as the rattled, eye-patched head of the military, Haim Bar-Lev (Dominic Mafham), vows revenge. “Teach them a lesson they will never forget,” Golda tells him. “We will crush their bones. We will tear them limb from limb,” he responds. When Bar-Lev loses his nerve, Golda places a new leader, David Elazar (Lior Ashkenazi), in charge. Meanwhile, a barrage of onscreen titles gives us names and titles, though few of the characters register as full personalities.

Although the film opens with a newsreel montage of significant events leading to Golda’s rise to power in Israel, beginning with the country’s nationhood in 1948, the filmmakers offer little insight to convey the existential and cultural stakes in the central conflict. Much of that responsibility lies on Mirren’s portrayal of Golda, who juggles battle lines, declining health, mental exhaustion, and negotiations with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (Liev Schreiber) for support. Tortured by her empathy for Israeli soldiers, she logs the numbers of every soldier killed, wounded, or held prisoner in a small notebook, and the losses weigh on her. Golda’s only confidant is her personal assistant Lou Kadar (Camille Cottin). Early on, Lou accompanies Golda to a secret meeting in a hospital, where the Prime Minister smokes until the last moment before her radiation treatments. Is Golda smoking endlessly as a form of self-punishment, or does she enjoy cigarettes that much? Only Lou might have some idea about Golda’s psychological state resulting from the conflict, to the extent that the 75-year-old advises her assistant to speak up if she sees any signs of dementia.

Nattiv conveys the mental toll on Golda in nightmare scenes, where the horrendous sounds of battle combine with phones ringing, whirling camera movements, and a crippling emotional breakdown. During such scenes, the excellent, disorienting score by Dascha Dauenhauer, which evocatively deploys a range of percussive instruments, supplies a vital method of capturing the complexity of Golda’s mind. Alas, Mirren must act in these scenes under a distracting prosthetic nose, jowls, and bushy eyebrows that often look inconsistent from scene to scene. From the first moment she appears onscreen, the effect is unconvincing; it never looks like anything except Mirren under a mask. The trick leaves the viewer constantly noticing whatever incongruity is happening with the makeup in a given scene—larger cheeks here, darker eyebrows there—and takes us out of the drama. Mirren’s natural face would have been close enough and may not have stopped some of the narrative thrust in its tracks. Only Tom Hanks in a fat suit is more off-putting (see Elvis).

Nattiv conveys the mental toll on Golda in nightmare scenes, where the horrendous sounds of battle combine with phones ringing, whirling camera movements, and a crippling emotional breakdown. During such scenes, the excellent, disorienting score by Dascha Dauenhauer, which evocatively deploys a range of percussive instruments, supplies a vital method of capturing the complexity of Golda’s mind. Alas, Mirren must act in these scenes under a distracting prosthetic nose, jowls, and bushy eyebrows that often look inconsistent from scene to scene. From the first moment she appears onscreen, the effect is unconvincing; it never looks like anything except Mirren under a mask. The trick leaves the viewer constantly noticing whatever incongruity is happening with the makeup in a given scene—larger cheeks here, darker eyebrows there—and takes us out of the drama. Mirren’s natural face would have been close enough and may not have stopped some of the narrative thrust in its tracks. Only Tom Hanks in a fat suit is more off-putting (see Elvis).

Curiously, the film lacks a sense of history outside of the Yom Kippur War. Born in what is now Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1898, Golda briefly recounts how she faced antisemitism from Russian soldiers as a child. It might have been more effective to show, not tell, these scenes from her past, giving us a sense of how she has had to fight her entire life. After all, Nattiv comes to this story having experienced the film’s war first-hand. He recalls in the press notes the rumbling of bombs as a three-month-old baby in Tel Aviv, cradled by his grandparents, both Holocaust survivors. “It’s as if my body remembers even if my mind cannot piece together why,” he writes, better conveying the many historical and cultural factors of the war than his film. Martin’s script isn’t quite sure if it’s an account of the Yom Kippur War or Golda’s subjective perspective on the events. It does neither very well.

Moreover, the film’s framing of the story around the Agranat Commission of Inquiry in 1974, which investigates whether Golda is responsible for any wrongdoing in her orders, adds little to the proceedings except to help the audience decide how to feel about what happened. If the Commission clears her, so should we, the filmmakers seem to say. It’s more complicated than that, of course. At one point, Golda supports an order to secure the line and not retreat despite inevitable failure, recalling the callousness of politicians in a similar situation in Paths of Glory (1957). At another point, the film shows her aching compassion for her people, specifically the soldiers who lose their lives, which she hears in military radio broadcasts. “I am a politician, not a soldier!” she declares later. However true, she’s also capable of discussing the conflict in her living room, having baked her generals a coffee cake—an image that almost disarms the viewer to the offscreen lives lost, presenting a fascinating contrast.

Alas, Mirren’s presence may prevent the target audience from connecting with the material—and not only because of the makeup work. The film has received some criticism over Mirren, who is not Jewish, taking on the role. Surely the prestige of her name motivated the choice. But along with her plastic-looking face, the extratextual concerns burden the production. The casting and uneven story treatment are a shame because Nattiv’s visual sense shows clear signs of a director capable of making drab 1970s offices and hallways compelling spaces. Dutch cinematographer Jasper Wolf offers striking imagery and fluid camera movements, enhancing our interest in thorny politics and military maneuvers. Editor Arik Lahav-Leibovich attempts to capture the frenetic editing style of Oliver Stone’s political thrillers, complete with stark black-and-white images that transition into color and actual archival footage with Mirren’s face digitally inserted into the scenes. But the film’s generous style and dramatic potential are crammed into a 100-minute movie that doesn’t adequately process its subject.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review